In Memoriam Ramón García Castro: Opera Aperta

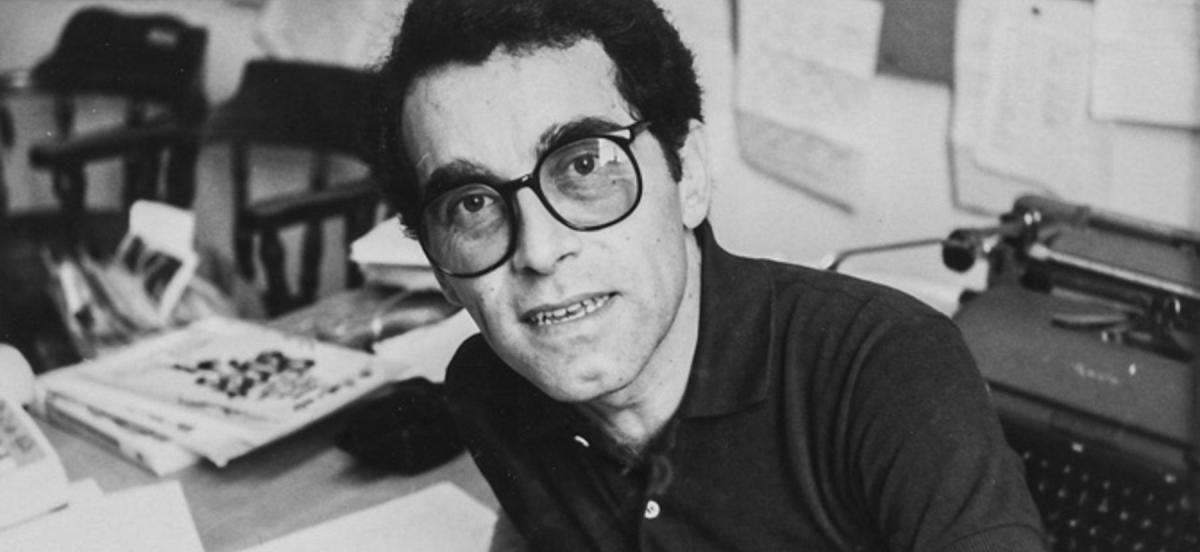

Ramón García-Castro, who died in June, was photographed by the author in 1982.

Details

Professor Emeritus of Spanish, 1940-2020

Ramón García-Castro (Santiago, Chile 1940 - Philadelphia 2020) taught Spanish language and contemporary Latin American literature during his thirty-four-year tenure at Haverford College (1972-2007). For long stretches of time he also served as chair of a department that he, along with Luis Manuel García-Barrio, co-founded (Spanish had previously been an appanage of French). As both a consummate translator and simultaneous interpreter prior to joining the faculty, Ramón was ideally suited to serve as emissary from the astonishing mid-century flowering of Latin American letters. Indeed, his initial years on the faculty coincided with the so-called Latin American "Boom" of novelists and poets whose works entered global circulation in translation. His offerings in this area, conducted in both Spanish and English, were highly popular with students at both Haverford and Bryn Mawr. Ramón also enjoyed a close bond with Latinx students, whose concerns he staunchly supported. His course titles expressed a broad range of scholarly interests: Literature of the "Boom," Caribbean Literature, Sexual Minorities in the Spanish Speaking World, Novísima ['most recent fiction'].

We lost Ramón this past May, in the midst of COVID-19 social distancing and remote everything; he is survived by his long-time partner, Benjamin J. Lariccia. As the pandemic lingers and unable to celebrate his life in person or read a memorial minute at the Haverford Faculty Meeting, we offer here instead the possibility of an on-line album to which we invite contributions (text, image) by former students and members of the faculty and staff in appreciation of all things Ramón. (You may add your own contributions to this album by following the link to the Department of Spanish Facebook page). Think of this as a virtual opera aperta/ 'open work' — to borrow Umberto Eco's notion of a text or work of art as an "open device," one in which to house memories or anecdotes of a beloved and dynamic teacher-interlocutor.

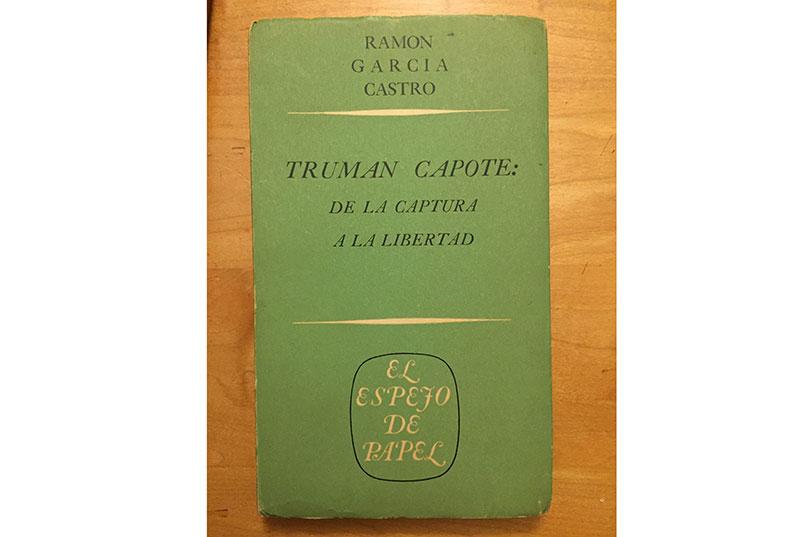

captura a la libertad."

A Chilean transplant in Philadelphia, Ramón remained chileno through-and-through; his intimacy with his land, its history, and, most important, his family back home, endured over his many decades of life here in El Norte.

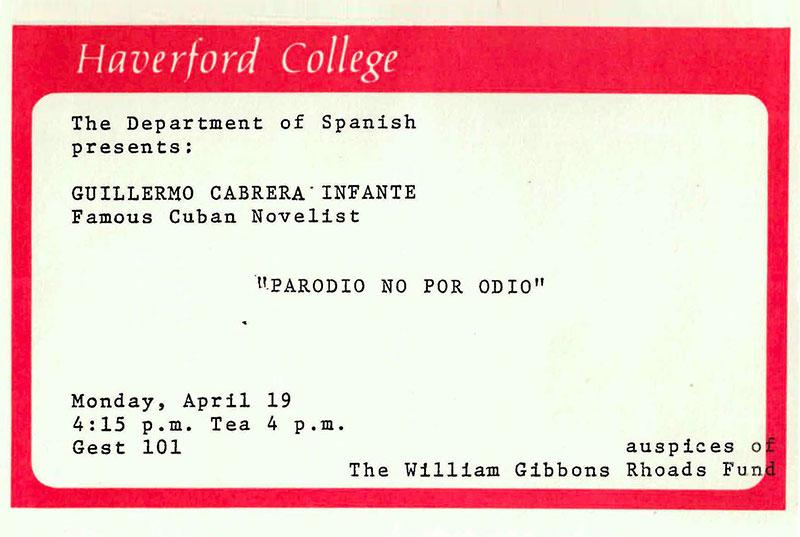

In referencing Eco's opera aperta we also highlight Ramón's privileging of vigorous classroom dialog and his rare gift for spot-on repartees. Socratic discussion, Ramón style, would often elicit his students' raucous laughter, something you couldn't miss if you happened to be in the hallway outside his classroom in Hall Building. By happy coincidence—or perhaps the work of a "synchronizing phantom," to borrow Vladimir Nabokov's coinage—a similar openness to readerly interventions characterizes much of the Latin American literary corpus he favored. Several of the writers he taught or wrote about share a multi-voiced and permeable aesthetic—as in the works of such diverse figures as Nicanor Parra, Julio Cortázar, Gonzalo Rojas, José Donoso, Luis Rafael Sánchez, Manuel Puig, Magali García Ramis, Isabel Allende or Reynaldo Arenas, to mention just a few. When Ramón first joined the faculty, Magill Library's holdings in this area were negligible, but they grew exponentially under his guidance. He also arranged for an important subset of these authors to visit and lecture under the auspices of the Distinguished Visitors Program. His cosmopolitan approach to teaching in a small liberal arts college was a boon to all and, as many will attest, an especially meaningful one to Latinx students, staff, and faculty in the Bi-Co. Looking back now at some of the luminaries that Ramón brought to campus we are simply awestruck; they visited his classes and delivered public talks or readings to eager audiences drawn from the surrounding Philadelphia area. In a moment we'll take a peak at some excerpts from Ramón's correspondence with some of his amazing guests.

Ramón's literary training began at the Centro de Investigaciones de Literatura Comparada, Universidad de Chile, under the tutelage of the eminent scholar, Roque Esteban Scarpa. It was don Roque, as Ramón always referred to him, who challenged and supported Ramón to take on ambitious projects while still a graduate student. In the brief space of five years (1964-69), Ramón published a critical study of Truman Capote's fiction, Truman Capote: De la captura a la libertad, along with his Spanish translations of two anthologies of Capote's short stories, El arpa de pasto and Un árbol de noche y otros cuentos.

A Fulbright fellowship brought Ramón to the US and Harvard's Comparative Literature program, where he earned the M. A. (1968). He subsequently moved to Philadelphia, where he taught at La Salle College while completing his Ph.D. in the Romance Languages Department at the University of Pennsylvania, with a focus on 20th-century Latin American literature (1972).

His doctoral dissertation on temporal perspectives in the novels of Alejo Carpentier laid the groundwork for subsequent studies of the Cuban author's strategic citations from visual culture—19th-century European painting, especially—in neo-Baroque fictions of colonial history. Ramón's writings would continue to display an abiding concern with narrative form in relation to national or ethnic identity formations; in later years he enriched his approach by also addressing such issues as sexuality, masculinities, and the body.

One especially illuminating essay, which appeared in Revista Iberoamericana (1996), brings into cross-hemispheric and body-centered dialog two rather distinct voices out of the gay closet, that of the "iconoclastic" (Ramón's characterization) Chilean man of letters, Benjamín Subercaseaux, and the unabashed chronicler of dissident sexual practices, Manuel Ramos Otero, a talented and provocative Puerto Rican writer living in New York City whose life was cut short by HIV/AIDS. Ramón's close and precise readings bring out the distinctive qualities of two writers who at first glance seem to inhabit entirely different worlds. This essay, in particular, infuses an academic paper with the same sort of attention and empathy that Ramón would lavish both in the classroom and around the table in the Faculty Dining Room of yore. His selection of these two gay writers, so vastly different at first glance, benefit from his characteristic probing interest. As Ramón argues, on closer inspection, each one instantiates modalities of the Foucaultian double bind of homosexual repression and discursive proliferation. In the case of Subercaseaux and his Santa materia (Holy Matter, 1954), a pseudoscientific treatise on racial and sexual typologies yields to a highly subjective privileging of two identity positions that are often denigrated. In Subercaseaux's hierarchy of male embodiment the Black man occupies the pinnacle of mind and body evolution, one truly comprised of "santa materia." But the subjectivity ascribed to him is one uniquely immune from same-sex erotic drives even as his corporeal temperament represents the telos of evolutionary physiology. In a similar fashion, the Chilean male that Subercaseaux also privileges belongs not to the élite, but the popular classes. As Ramón observes, both exaltations rest on problematic assumptions regarding class or race-identified habits and ethics. Regarding the ordinary chileno, the author shuffles praise and biases: "al que se lo admira por su valor, por su resistencia, pero disgusta su embriaguez, tendencia al robo y afición a las riñas"/ 'who is admired by his valor, his resistance, but is regarded with disgust for his drunkenness and affinity to robbery and brawling' (154). Nevertheless, in Ramón's analysis the zig-zagging portrait of the common man bespeaks with rare candor the writer's erotic preferences and closeted sexuality. Turning next to Ramos Otero's short story, "Vida ejemplar del esclavo y el señor" (1983), Ramón notes that the sado-masochistic master-slave dynamic deconstructs a presumably stable and historically weighted master-slave binary. The ensuing spectacle of identitarian dynamics paradoxically asserts and challenges forms of mastery. In Ramón's illuminating conclusion, "la represión sexual, por lo tanto, matiza, carga el discurso de estos dos escritores, de alejamiento, de soledad, y, debido a la diferencia de generaciones, de violencia flagrante en el caso de Ramos Otero, pero afortunadamente no impide la confesión de la que habla Foucault" (161) / 'Sexual repression, therefore, shades and charges the discourse of these two writers with estrangement, solitude, and, owing to generational differences, with violence in Ramos Otero, but, fortunately, does not impede the confession that Foucault describes' (my translation).

Distinguished Visitors

Below you'll find selected images of Ramón's correspondence with several Latin American writers whose visits he hosted; the year of their visit to campus is in parentheses. We are grateful to the Haverford College Archives for making available images of Ramón's correspondence. The complete archive is also available in the Department of Spanish web page, https://www.haverford.edu/spanish/history

I provide selected transcriptions and English translations.

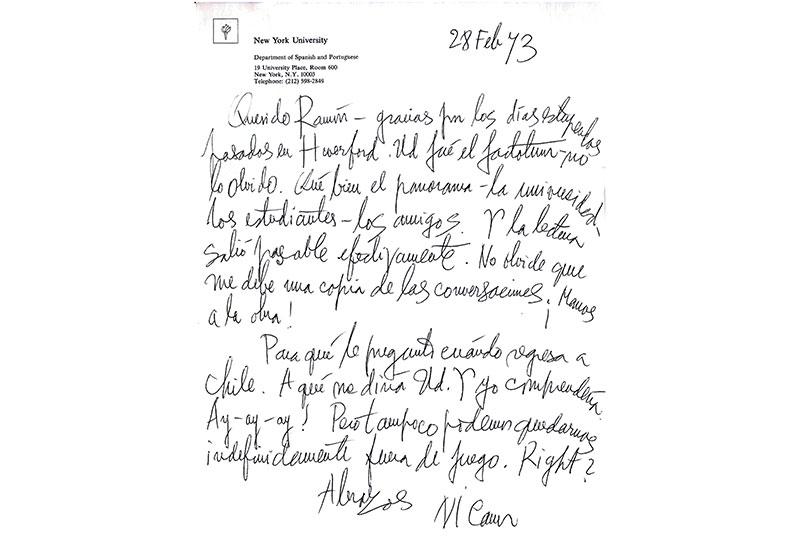

Nicanor Parra (1973)

Querido Ramón — gracias por los días estupendos pasados en Haverford. Ud. fue el factótum - no lo olvido. Qué bien el panorama- la universidad - los estudiantes - los amigos. Y la lectura salió pasable efectivamente. No olvide que me debe una copia de las conversaciones. ¡Manos a la obra!

Para qué le pregunto cuándo regresa a Chile. A qué me diría Ud. Y yo comprendería. Ay-ay-ay! Pero tampoco podemos quedarnos indefinidamente fuera de juego. Right?

Abrazos

NI Canor [Nicanor]

Dear Ramón — thanks for the stupendous days spent at Haverford. You were the factotum - I don't forget it. How nice the panorama — the university — the students — the friends. And the reading went passably well in fact. Don't forget you owe me a copy of the conversations. Do it!

Why do I ask when you're returning to Chile. Why, you might say. And I would understand. Ay-ay-ay! But we cannot remain indefinitely out of the game. Right?

Hugs

NI Canor [Nicanor]

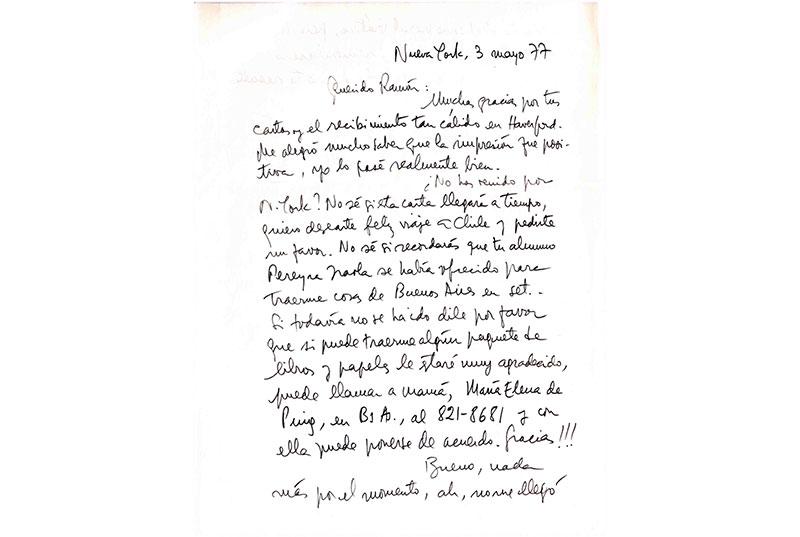

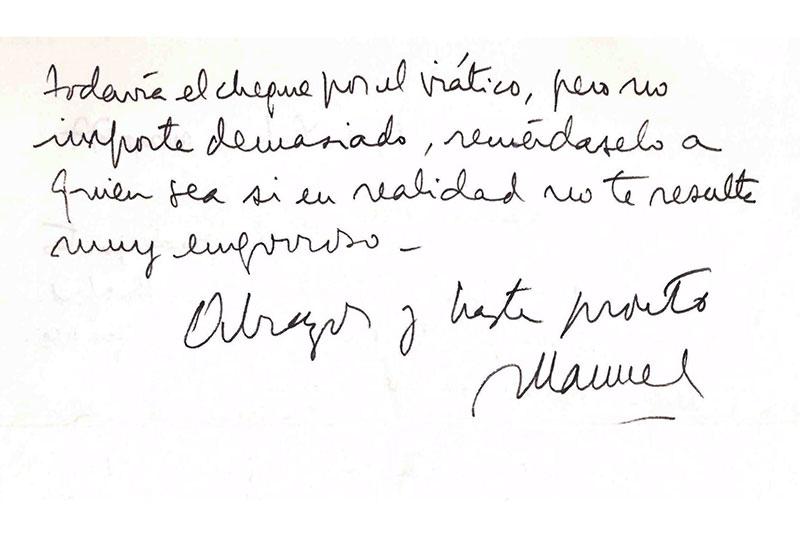

Manuel Puig (1977)

The writer expresses his gratitude to the host and the students who attended. One of these offered to bring back from Buenos Aires a package of books and papers from Puig's mother. In the letter Puig includes his mother's phone number for the student to contact her: "María Elena de Puig, en Bs. As. [Buenos Aires], al 821-8681." He adds at the end that his Haverford honorarium has not arrived yet.

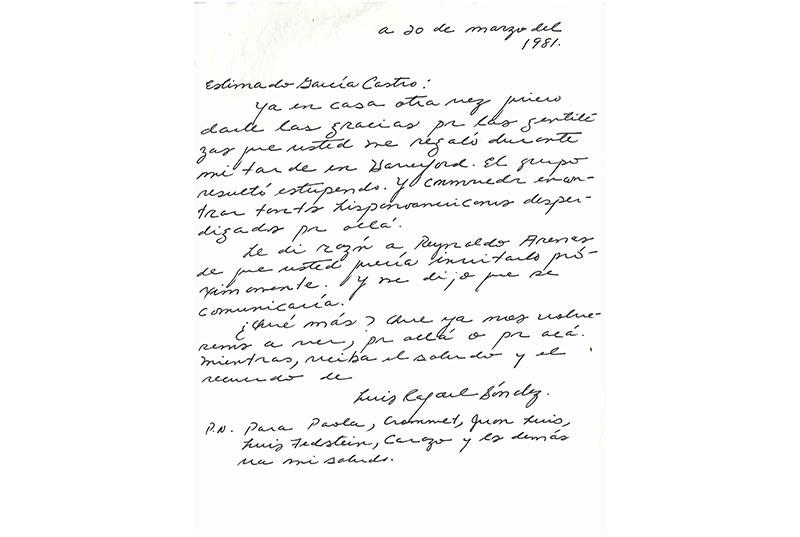

Luis Rafael Sánchez (1981)

In Ramón's letter of invitation (not reproduced here) he points out that Haverford is a small college, so don't expect a mob scene at the talk: "Le prevengo que el college es chico, así que no espere encontrarse con un gentío para su conferencia."

Sánchez's hand-written note expresses how moved he was to find a wonderful audience—"el grupo resultó estupendo"— and so many Latinxs on the campus, "conmovedor encontrar tantos hispanoamericanos desperdigados por allá." He also reports that he has informed Reynaldo Arenas of Ramón's interest in inviting him to campus. PS: He sends regards (by name) to some of the students he met during his visit: "I send greetings to Paola, Crommet, Juan Luis, Luis Feldstein, Carazo, and the others."

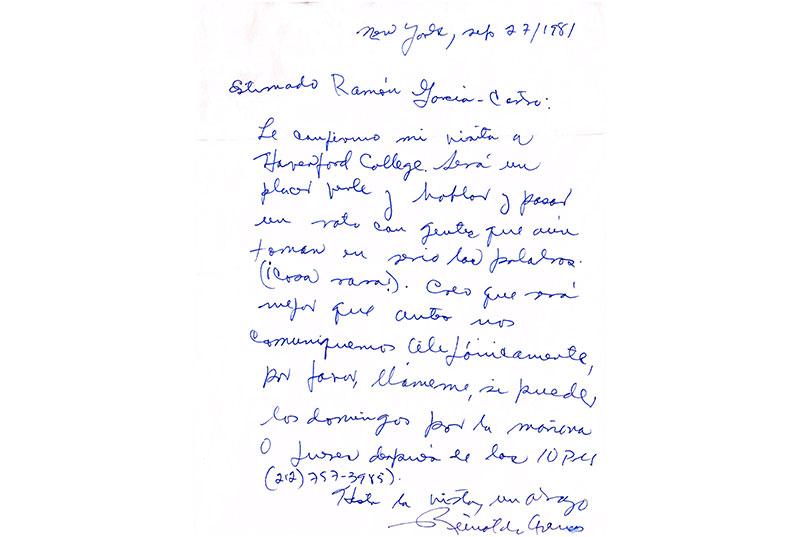

Reynaldo Arenas (1981)

Arenas looks forward to meeting Ramón 'and to spend some time speaking with folks who still take words seriously (Rare thing!)' / "y hablar y pasar un rato con gentes que aún toman en serio las palabras (¡Cosa rara!)."

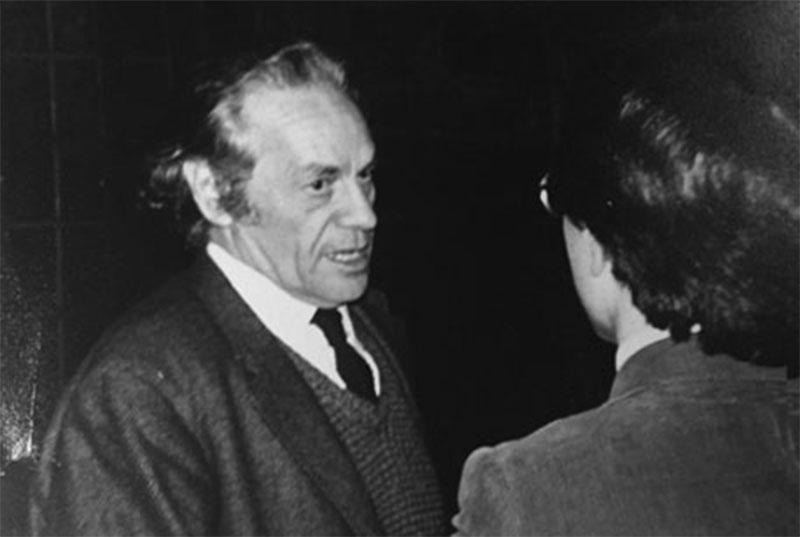

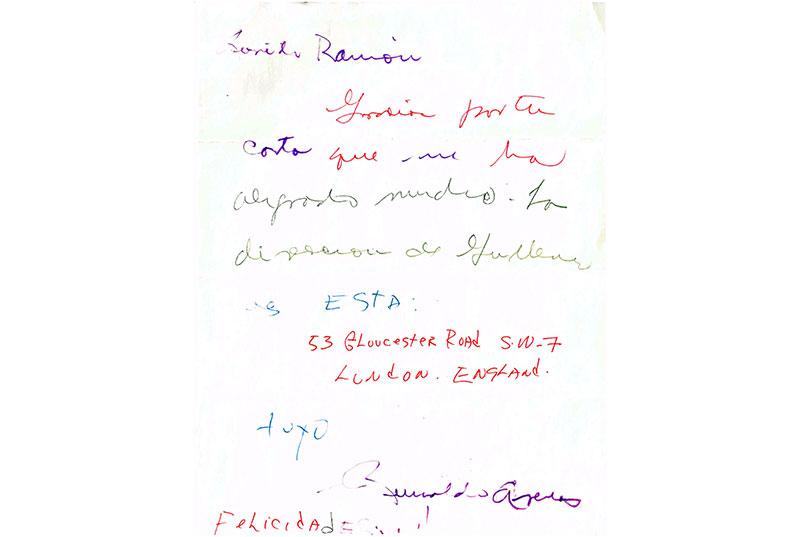

Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1982)

Ramón and the Haverford campus

The beauty of the Haverford campus—arboretum, vistas, historic buidings—was something he cherished. As Ben Lariccia notes, Ramón was a keen observer of the trees around campus, paying close attention to individual specimens and lamenting the toppling of some of the majestic, old ones. A tree planting in Ramón's memory is currently in the works, to be realized in the spring.