Studying Historical "Madness"

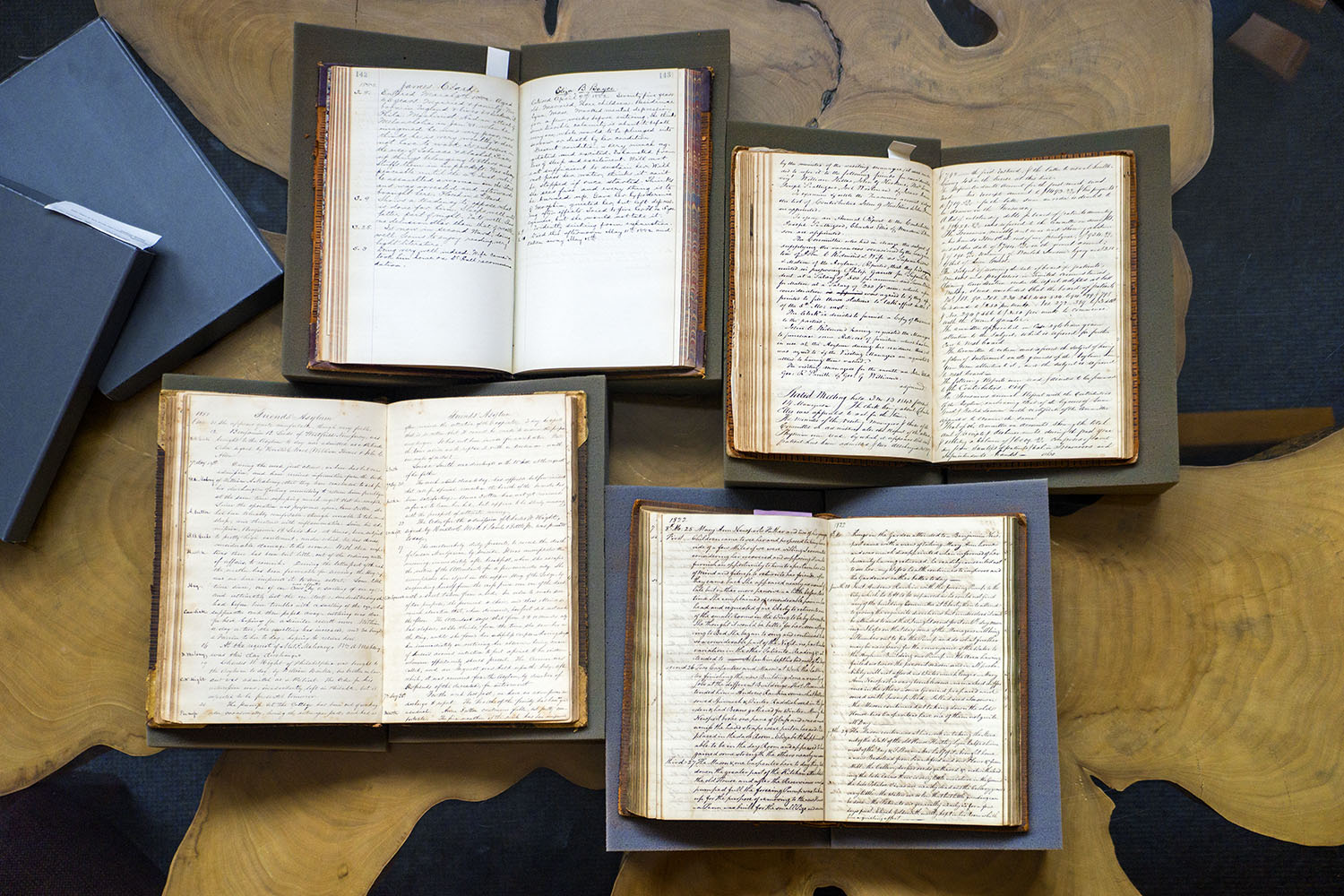

Associate Professor Darin Hayton (standing) and the students in his class "Madness" in Special Collections.

Photos by Patrick Montero

Details

In Darin Hayton's 300-level seminar, students are using primary sources from the country's first Quaker-run psychiatric hospital to explore roughly 150 years of treatment of the mentally ill.

More than 175 years after a female patient challenged the male superintendent of the country's first Quaker-run psychiatric hospital, students in Associate Professor Darin Hayton's 300-level history seminar were discussing her actions, his reactions and what those revealed about both people and the era in which they lived.

Ruth Scott was 30 years old when she entered Friends' Asylum — officially called "The Asylum for Persons Deprived of the Use of Their Reason" — in 1820. Isaac Bonsall was the superintendent, on the job since the hospital's doors had first opened three years earlier. One of the asylum's day books, meticulously maintained by Bonsall, gave the class fodder for their analysis.

"It's riveting. It really is. I often find I can't pull my eyes from it," said Hayton of the unique collection of Friends' Asylum primary sources in Haverford's care. "This is the first class and first group of people in any real sense to use any of them. There have been two books written about the Friends' Asylum that use some of this material, but most of it has been ignored or has escaped attention."

Hayton, a science historian, had long known the documents existed in the library's Special Collections department but had mistakenly thought them off -limits. That changed last year and he began reading some of the documents. He was immediately hooked — "All of my friends had to put up with me telling them about my new friends, these dead Quakers, and the horrible things that had happened to them," he joked — and he saw a clear teaching moment. Students in this class, "Madness," are completing research projects using the materials.

"Broadly put, the way a society deals with its insane tells us a lot about that society," says Hayton. "This is an amazing opportunity to see what people in the early 19th century thought were the best things to do," he said. "To our minds, the things they do might seem really horrific or barbaric but they really believed they were helping."

In 1600s England, many outsiders assumed those belonging to the Society of Friends had mental issues. Their tenet that everyone had access to God without the need for an external authority was dubbed radical. The now-common shorthand for the Friends, "Quakers," was meant to be an insult referring to worshippers who would shake with emotion during services.

Many Quakers left England because of this persecution. But while the Quakers found religious freedom in the New World, those with mental disorders were still treated cruelly. After visiting a Quaker-run psychiatric institution in England that stressed humane treatment of patients, influential Minister Thomas Scattergood returned to Philadelphia and persuaded local Quaker leaders to build a similar institution.

Instead of a dank, dirty facility where the mentally ill were ignored or punished, Friends' Asylum's main building was designed so patients would be exposed to natural light and fresh air. The original structure still stands on its original grounds in the Frankfort section of the city. Appropriately, it now houses the Thomas Scattergood Behavioral Health Foundation, a Quaker-based, philanthropic organization established in 2005. This past summer, the foundation entrusted Haverford with the few remaining boxes of original documents it still had and a $40,000 grant to fund archival preservation, student researchers, and the establishment of an online web portal for the materials.

"This group of Quakers were pioneers in redefining how people with mental illnesses were treated in this country," Scattergood President Joe Pyle said. "They were the pioneers around moral treatment and establishing a caring community and recovery and they don't get the credit they deserve. We talk about how far we've come, but we should always be mindful of where we've been."

Besides day books maintained by asylum superintendents, the collection includes intake documents, patient medical records, building design plans, treatment guides, and annual financial reports. The papers date from the early 1800s and run through the mid-1900s.

"It's important to study the history of marginalized people, and people with mental illness have definitely been marginalized in history. This is a way of honoring their memory," said Abigail Corcoran '17, who spent last summer exploring some of the documents and providing text for the website. "It's really sad to see what people thought would be helpful to them. They really were trying their best."

Insanity, as these early Quakers understood it, was a temporary state that stemmed from a variety of issues. Mania and melancholy were two of the most frequent underlying causes, but the notes indicate some patients were considered insane because of business anxieties or severe grief after losing a loved one. The hospital administration most wanted patients who were newly insane because they believed that would make them more likely to be rehabilitated and released. One record book notes the dates and reasons for patient discharges: Restore, improved, much improved, stationary, or died.

Among the treatments considered most effective for curing insanity were "shower baths," which including dumping buckets of cold water on patients to either liven them up or calm them down as needed; "blistering," which was applying bandages covered in dried Spanish flies to a patient's shaved head to produce swelling or pus; and dosing with "salts." In an 1817 day book entry, Bonsall writes that the asylum has been given an "Electrical Machine," a "valuable present" from the hospital's managers. It's no doubt fortunate for the patients that the machine's complexity meant no one in Philadelphia knew how to use it until a visitor in 1820 demonstrated the proper way to use it.

Ruth Scott spent about four years as a patient in Friends' Asylum and was classified as "improved" when she was discharged in 1823. Scott believed she was a divine messenger and fought to be allowed to attend weekly worship meetings. At one point, she ran away from the asylum to hear controversial preacher Elias Hicks, whose beliefs caused the first major schism in the Quaker religion.

In her class presentation, Heller focused on four of Bonsall's day book entries that mentioned Scott. In one, he noted Scott said he and his wife, who worked with female patients, were cruel. She also said not allowing her to attend services — or to dictate that she attend worship but not speak — was an insult not only to her but to "God Almighty."

After Heller, other students presented research on how a suicide was recorded in multiple hospital logs and the asylum's conclusion that the best way to treat a woman who had gone mad when here husband confined her to their home was to confine her to the hospital.

"This reminds us that what we're doing today is going to look horrific to the next generation," Hayton said. "Every generation thinks they've got it figured out and every generation thinks they're discovering the truth about the natural world, and, if history shows us anything, it's that every generation is wrong about that."

–Natalie Pompilio