Digitally Preserving an Indigenous Mexican Language

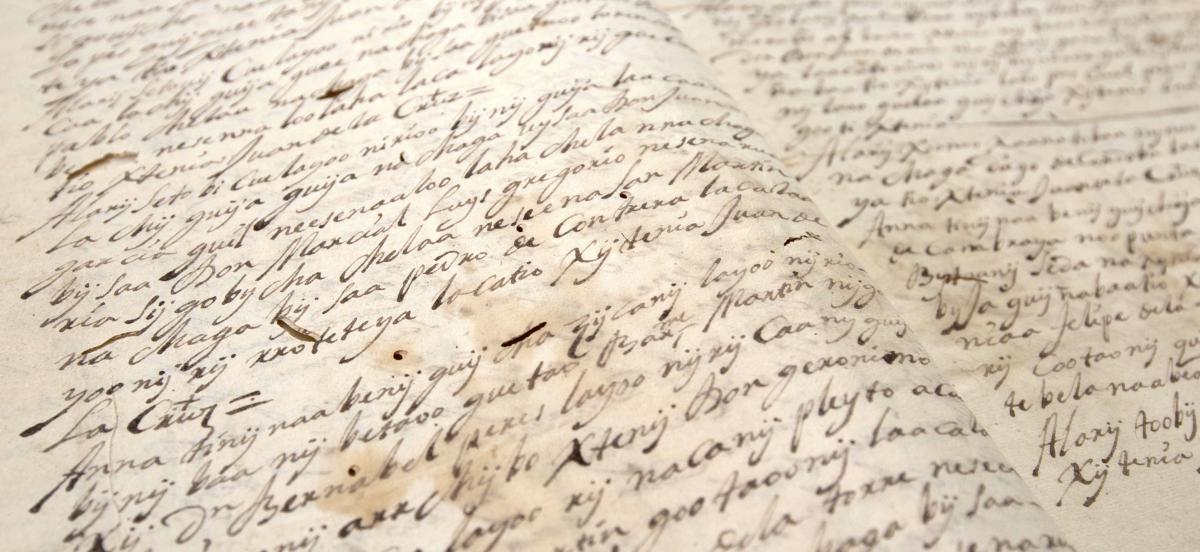

A Zapotec document at the Archivo General de Poder Ejecutivo de Oaxaca in Oaxaca City. Courtesy of the Ticha Project.

Details

The Ticha Project, started by Assistant Professor of Linguistics Brook Danielle Lillehaugen and her collaborators, is a new online explorer for a corpus of Colonial Zapotec texts.

Currently on an 18-month sabbatical from teaching, Haverford Assistant Professor of Linguistics Brook Danielle Lillehaugen recently returned to campus from an exciting treasure hunt for Zapotec texts during a three-week research trip to Oaxaca, Mexico. Zapotec is a language family indigenous to southern Mexico, and one of its dialects—Colonial Valley Zapotec—though now extinct, is preserved among written Zapotec documents that survive from the period 1500-1800s. The language, which faces discrimination in the country, is also one among the many endangered languages around the world at risk of extinction.

Lillehaugen was on the lookout for Zapotec manuscripts that she hopes to add to the growing collection in the Ticha Project—a digital publication of Colonial Zapotec resources, including texts, translations, images, and linguistic commentary.

“There’s a lot of work in this project that I just really love to do,” she says. “I often find myself turning to it for fun, which I think is one way to know if you are really doing something you like. Even after a long day, even after you are tired, if you still want to work on it—maybe you have found something.”

Origin Story

Lillehaugen, who initiated the project, became interested in the study of Zapotec languages the summer before starting her M.A. in linguistics at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her dream of one day translating, annotating, and analyzing Zapotec writings and making it available to the public was realized almost a decade later when she joined the Haverford faculty in 2012.

She created the Ticha Project in 2013 with the support of Laurie Allen, the coordinator for digital scholarship at Magill Library, who suggested that this project could be bolstered by a digital format. Ticha currently has around 30 texts available online—some as a short as one-page, hand-written manuscripts and others containing nearly 300 pages.

“I think that the digital format allows a lot of flexibility that a print format never would,” says Lillehaugen, “I’ve really been impressed with how the collaboration has gone. [And] what we’ve managed to do over a few years in terms of making a resource that has a significant amount of content on it.”

Lillehaugen and Allen's Ticha outside collaborators include George Aaron Broadwell, a professor of linguistics and anthropology at University of Albany, SUNY; ethnohistorian Michel R. Oudijk; and Enrique Valdivia, a Ph.D student at University of Albany, SUNY.

Awarded funding from many channels including the National Endowment for the Humanities, Ticha is an ongoing project that seeks to make accessible and promote the Mesoamerican language of Zapotec to academics, students, and to the Zapotec community. Another chief purpose of the project is to understand Zapotec history from writings in Zapotec itself.

While the oldest known Zapotec text is from 1565, the majority of the texts are from late 1600s and early 1700s, and the writing practice stopped sometime in the mid to late 1700s. There are nearly 300-400 manuscripts just from the Valley of Oaxaca, where Lillehaugen is working. However, only a small portion of those are represented in the digital archive, as the project is trying to acquire high-resolution images of texts, and secure permission from archives to present these manuscripts online.

The skeleton of Ticha is essentially a complex dictionary—a lexical database—that the team created while analyzing the many Zapotec texts. The dictionary is constantly evolving and being improved upon by Broadwell and Lillehaugen so that they can analyze future texts more efficiently.

Allen, the digital humanities expert, is working on a third goal of the project: crowdsourcing. Ticha’s crowdsourcing feature would allow interested users to contribute possible transcriptions of Zapotec texts to the editorial team. This will not only speed up the transcription process, but also allow more direct community participation in the project.

“If we are really fully embracing digital humanities and digital publications, then I think the two way conversation is something that shouldn’t be left out," says Lillehaugen. "This ability to crowdsource is something that we should take advantage of.”

On The Road

Last summer Lillehaugen was in Oaxaca with her student research assistant May Plumb '16, and the duo searched major archives for Zapotec manuscripts. But this year Lillehaugen is on a solo search, exploring smaller church and municipal archives in Oaxaca. This process is slower as most of these smaller archives do not have an existing log of what exists in their collection. Hours could be spent without finding anything. But in the town of Tlacolula de Matamoros, for example, Lillehaugen found four Zapotec documents from the municipal archive.

“You have to show up and look through the boxes and not get discouraged because even if you find one or two then the whole trip is worth it,” she says.

In the future she hopes her team can collaborate with Mexican students and universities on this project in order to make it a truly multilingual, interdisciplinary, and international endeavor.

The study of Zapotec is not simply a passionate academic interest for Lillehaugen. Her fieldwork with the Zapotec people in Mexico has developed this project into something much more meaningful. The Zapotec are told that theirs is not a real language, that is it just a dialect. Yet to realize that Zapotec has a rich written history and having access to these centuries old texts helps build a powerful relationship between the people, their town, and their language.

“The reaction from Zapotec community members is always so positive!” says Lillehaugen. “It even sometimes brings me to tears when I get to be in a position where I am showing people texts written from their town, 400 years ago, that they didn’t know existed at all. I think those moments when I can help connect people to their own written history, in their own language, has been some of most powerful moments in the field for me.”

—Hina Fathima ‘15