Revitalizing Endangered Languages Remotely

A Haverford team continued work virtaully with language activists and activists on Talking Dictionaries this summer. Nuria Benitez '22 (big window) and Felipe Lopez, a Haverford postdoctoral scholar in community engaged digital scholarship, collaborated via Zoom.

Details

This summer, a team of Haverford students, faculty, and staff supported language activists and educators in creating Talking Dictionaries virtually.

Of the approximately 7,000 languages in the world, roughly 43% are classified as endangered by UNESCO. Talking Dictionaries are a resource for community activists working to revitalize endangered languages.

“Sharing our language online gives us an opportunity to let people know that we exist and our language is still alive,” said Felipe Lopez, a San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec speaker and Haverford postdoctoral scholar in community engaged digital scholarship.

Lopez has been working to preserve his endangered variation of Zapotec since 1992. In 2016, he started working with Haverford Associate Professor Brook Danielle Lillehaugen to create a Talking Dictionary, and since then, it has grown to 2000 entries and has become a resource for the Zapotec communities in Oaxaca, Mexico and Los Angeles, Calif.

The longtime Talking Dictionaries project, an initiative started by Swarthmore Linguistics Professor K. David Harrison in 2005, digitally compiles words and phrases in endangered languages. It now includes over 200 languages, including six different Zapotec languages, thanks to the work of Lillehaugen.

These Talking Dictionaries are tools for language educators, activists, and communities to use how they wish. They can provide a window into a community for outsiders or a living compilation of knowledge.

“Importantly, each dictionary explicitly belongs to its respective community who retains intellectual property rights,” said Nuria Benitez ’22, “and there is always at least one community member co-author.”

This summer, work on the Talking Dictionaries was able to continue despite COVID-19. Teams across the Tri-Co worked virtually to build up collections, including eight new ones such as Kumyk, Yawa Umat, and Tai-Khamti. The Haverford team of Lillehaugen, Benitez, Neal Kelso ‘20, Visiting Assistant Professor of Linguistics Kate Riestenberg, CPGC Fellow Janet Chávez Santiago, and Postdoctoral Scholar Felipe Lopez continued work on three different Zapotec dictionaries—San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec, Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec, and Tlacochahuaya—from their respective homes.

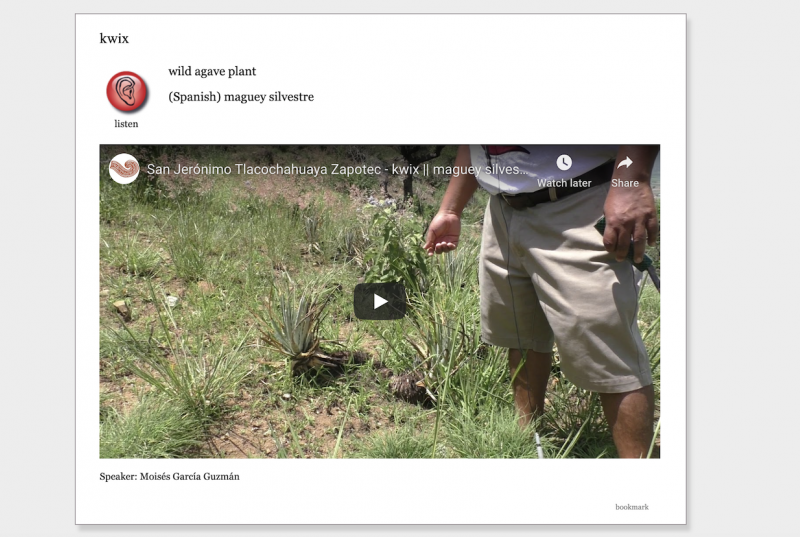

The dictionaries are multi-media collections, featuring embedded tweets and Youtube videos, that explain how words and phrases have evolved through conversations with communities about what they want to be able to do with their dictionaries.

"García Guzmán, the director of the Tlacochahuaya dictionary, told us—words lead to stories, that lead to more stories,” said Lillehaugen. “When we worked to document plants in his community, he wanted to include important information on how to process the plant—that is often best shown with video.”

In the Zapotec dictionaries, tweets demonstrate how Zapotec words are used in the cultural context.

“For example, in the entry for ‘gyaluzh,’ we explain that the tender branches of this tree are used in a ceremonial healing process, which is being lost due to the introduction of Western medicine,” said Lopez.

The day-to-day work on Talking Dictionaries involves facilitating the recording of entries into the dictionary, combing through print sources for words and phrases to add, and translating phrases from Zapotec to English and Spanish. Creating the dictionaries is a lot of work, and students are important collaborators. These students learn technical and interpersonal skills, including respectful collaboration with Native communities.

Kelso has worked on Zapotec Dictionaries since the spring of 2019. He incorporated this work into his senior thesis, in which he produced a preliminary description of the plant taxonomy of San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec. His thesis also proposed ways for the presentation of the taxonomic system to be improved in the Talking Dictionary. This summer, Kelso created lists of animal species in different areas that included images and scientific names. These lists will be provided to community dictionary directors.>

“They will be taken into the field in the future to help document the environmental knowledge held within these communities and their languages,” said Kelso.

Dictionary directors could use these lists to collect the names of common indigenous names’ of animals or to collect other information, but what directors and communities choose to do with these lists is up to them.

COVID-19 did, however, change how the team worked. Most years they would be in Oaxaca, Mexico, collaborating with native Zapotec speakers. This summer, they were spread across the globe, working virtually.

It was Benitez’s first experience working with Talking Dictionaries and Zapotec languages. And though she learned about some parts of the language from videos and textbooks, she found it hard to not be on site.

“Although my work does necessitate knowing the language well, being detached from the language and the culture does make my work more challenging,” said Benitez.

Despite the challenges that the summer brought, the team still made progress.

“Students were able to make progress on some of the necessary but time-consuming work that requires more hours in front of a computer,” said Harrison. “All while interacting remotely with dictionary leaders.”

“The fact, the students and the Zapotec leader continued with these dictionaries despite that shows how dedicated everyone is to the project,” said Lillehaugen. “Let's hope next year we can continue the work on Zapotec land.”