Physics Students Publish Peacock Research

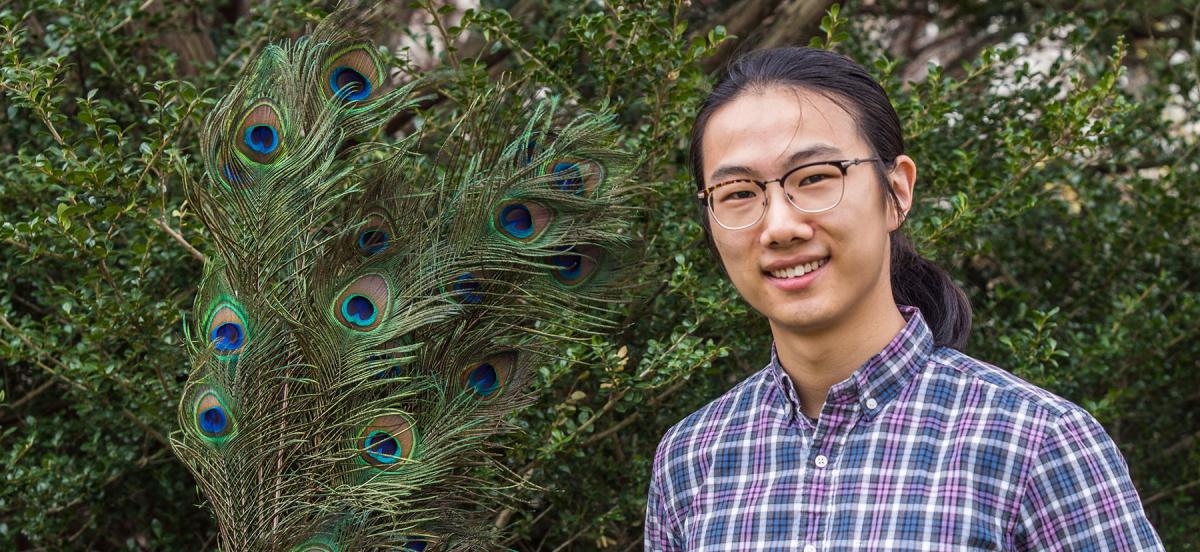

Yuchao Wang '20 poses with peacock feathers, the focus of his research with Yabin Lu '18, Rui Fang '18, and Professor of Physics and Astronomy Suzanne Amador Kane. Photo by Patrick Montero.

Details

Yuchao Wang ’20, Rui Fang ’18, and Yabin Lu ’18 co-authored a paper in PLOS ONE with Professor of Physics and Astronomy Suzanne Amador Kane on the biological physics of the color of peacock feathers.

Many birds are known for their vibrantly colorful and flashy feathers, but does their plumage make them more visible to predators? This was one of the key questions Professor of Physics and Astronomy Suzanne Amador Kane sought to answer when beginning her research on how colorful peacock and parrot feathers appear in the eyes of predatory mammals..

“We began this project in spring 2017 as part of [Class of 2018 members] Yabin Lu and Rui Fang's senior thesis research,” said Kane. “They had been working on an imaging and spectroscopy study of how iridescent feathers change their color and brightness when birds perform elaborate courtship displays. While doing this work, I started thinking about how different animals have radically different color vision.”

For example, Kane explained, it's not clear whether cats can distinguish red cardinals at a bird feeder from the green leaves surrounding them. If mammals that prey on birds cannot distinguish their vibrant colors from surrounding vegetation, this means that evolving plumage to appeal to females may be less risky than previously thought.

“Most humans have three cones in the retina of their eyes,” Kane said. “Cats and dogs have only two, so they cannot distinguish red, orange, yellow and green as different colors. Birds, on the other hand, have four types of cones, including one type which can detect ultraviolet light that human eyes cannot see! It turns out that dogs and cats have similar ultraviolet vision to many birds, including the wild species of cats and dogs that hunt peacocks, parrots, and other birds in their native habitats.”

Fang, Kane, and Lu’s research continued over the summer of 2018, and Yuchao Wang ’20 joined the team. Now, the three students and Kane (along with co-author Roslyn Dakin of the Migratory Bird Center at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Washington, D.C.) are publishing their findings in PLOS ONE, a multidisciplinary science journal.

“This publication means a lot to me,” said Wang, who is pursuing a major in cognitive science through Swarthmore College. “Being involved from the experimentation to the peer-review process gave me a much clearer appreciation of being in academia, and taught me care and perseverance in my future research.”

The three-year-long research project was intense, meticulous, and rewarding for the three student co-authors. Using techniques like reflectance spectroscopy and multispectral imaging to analyze the visual characteristics of peacock feathers from a predator’s perspective taught them new, highly technical skills.

“To make a convincing scientific argument was extremely challenging,” said Kane. “We measured and analyzed many different feathers from different species using specialized cameras that photographed the feathers through different filters, along with computer programs designed to simulate the color vision of each species. Yuchao's background as an independent cognitive science major was a huge asset—he did an amazing job performing the many different types of measurements and learning the complicated quantitative vision models.”

In 1888, Charles Darwin stated that “even the bright colors of many male birds cannot fail to make them conspicuous to their enemies of all kinds"

Ultimately, Kane and her students’ study challenges this. “On the contrary,” reads the article, “our study implies that some species of birds that appear vividly colorful to humans and other birds may appear drab and inconspicuous in the eyes of mammalian predators.”

All three students have bright futures in biological physics. After graduation, Lu returned to her home country of China to seek research opportunities there, and Fang is pursuing her master’s in computational science and engineering at Harvard University. As for Wang, his upcoming senior year at Haverford won't be the end of his work in cognitive science.

“I greatly appreciated the interdisciplinary nature of the research, which allowed me to draw connections from neuroscience and biology, and still ground its methods and analyses in physics," he said. "I will definitely be pursuing further research in cognitive neuroscience and neuroaesthetics, an important component of which concerns the visual system. So the knowledge I acquired in this research will certainly be valuable in the future.”