Zachary Oberfield's New Book Tackles Charter School Debate

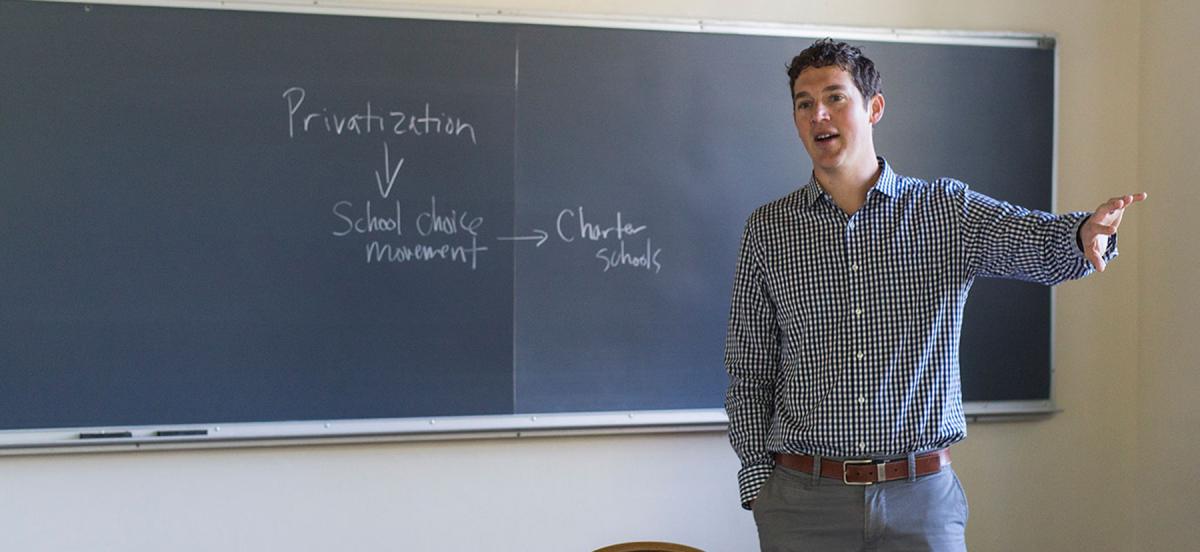

Associate Professor of Political Science Zachary Oberfield. Photo by Patrick Montero.

Details

The associate professor of political science talks about the book, which The Washington Post said should be required reading.

Ever since the first U.S. charter school opened in Minnesota in 1992, the debate about charters (publicly funded schools that operate independently of local districts) has been going on at high pitch. In July, Associate Professor of Political Science Zachary Oberfeld jumped into the middle of that discussion with the publication of his new book, Are Charters Different? Public Education, Teachers, and the Charter School Debate (Harvard Education Press). Washington Post columnist Jay Mathews called it “the fairest, deepest, and thus most frustrating book on that subject in a long time. People on both sides of the debate will find facts in it we don’t like. That is why we should be required to read it.” Haverford magazine editor Eils Lotozo spoke to Oberfeld about what his research revealed.

Eils Lotozo: So are charters different?

Zachary Oberfeld: Yes and no. The aim of the charter school movement was to give teachers and schools more autonomy and to make them more accountable. From what I can tell, they’ve achieved half of that goal. They’ve allowed teachers to bring more of their own experience and creativity into the classroom and to participate in making decisions about their schools. But I don’t see much difference in terms of accountability, the idea that if you do a good job you are going to get a reward, and if you do a crappy job you will be let go. So we have schools that are giving teachers a bit more power, but they are not necessarily ensuring quality in the way the people who came up with the charter idea envisioned. But here’s something else I found. There has been a lot of concern that charter schools are different from traditional public schools in being worse places to teach—that they’re high turnover, exploitative, miserable places to work. But I found no evidence to suggest that charters are much different in terms of teacher satisfaction and turnover.

EL: What does the growth of charter schools mean for traditional public schools?

ZO: Where charter schools are located, in mostly urban areas, it used to be that kids would just go to the school in their neighborhood. Now there are options. Charters mean that there is increasing competition, and public schools are being forced to change how they interact with their communities. In a lot of places the funding follows the student, so for every student a district loses to a charter, [it has] less money to spread around. I think a fire has been lit under public school administrators to figure. We’ve seen stories of principals going door-to-door trying to sell their schools. You can say, “That’s good. They’re not a monopoly anymore.” But the flipside is that administrators are devoting resources to things like recruitment, and every dollar you spend recruiting students, you are not spending on educating them.

EL: Charter schools have much less public oversight and control. Are you concerned about the democratic implications of that?

ZO: Yes, I am. The positive side of the story is that charters have the potential to empower parents to have more control over one of the most vital decisions they make. If choice is not just a buzzword, but is something parents get value out of, I think that’s a powerful thing. However, when you give public dollars to a private entity, it’s incumbent upon us to know what’s happening in [that place.] The concern is there is not a strong framework in a lot of states for overseeing charter schools and making sure what happens in them is on the up-and-up. Of course, there is a tension between control and the ability to innovate. If we made charters just like public schools, whose budgets are much less flexible, there is the potential to eviscerate their dynamism. So I think the key question for communities and policymakers is: How do the gains in school-level discretion and parent empowerment stack up against the costs of losing public oversight? To put it another way, I think we need to acknowledge that moving toward a charter-centered education system entails some trade-offs.