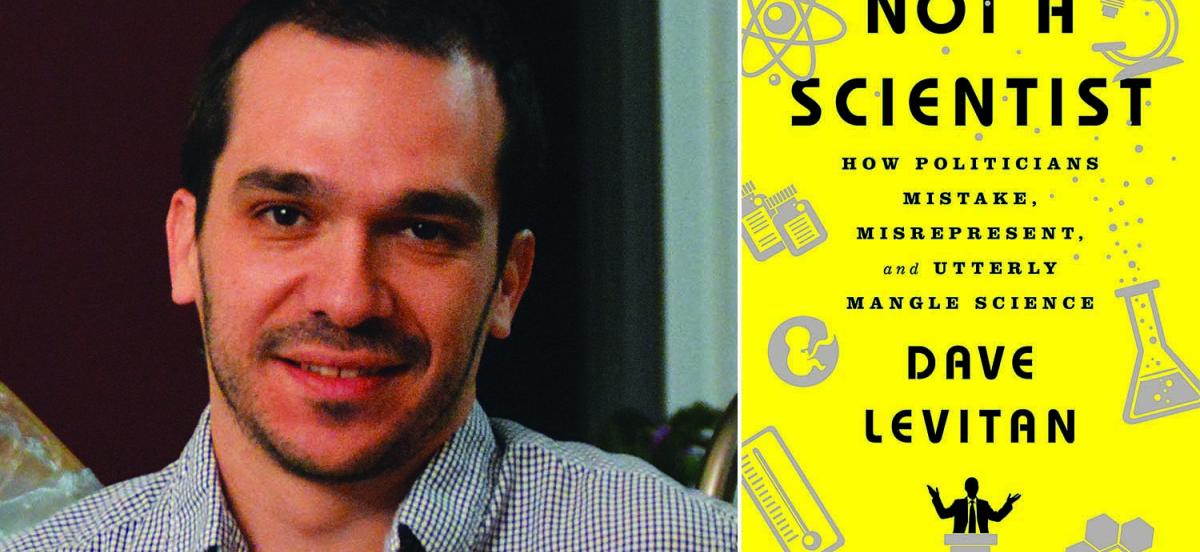

Science Journalist Dave Levitan '03 Publishes First Book

Details

Not a Scientist: How Politicians Mistake, Misrepresent, and Utterly Mangle Science, which was published in April by W.W. Norton, outlines 12 common tactics that politicians regularly employ to butcher science, including “the Cherry-Pick,” “the Literal Nitpick,” and “the Oversimplification.”

Journalist Dave Levitan spent his teen summers working in neuroscience labs, dissecting squid and learning the value of basic scientific inquiry. Though he ultimately chose English over physics for his Haverford degree, that scientific curiosity followed Levitan through his early work as a medical writer, and as the first person ever hired by FactCheck.org to track the errors—deliberate or otherwise—that politicians make when they talk about science. The lessons he learned at that gig led to Levitan’s first book, Not a Scientist: How Politicians Mistake, Misrepresent, and Utterly Mangle Science, which was published in April by W.W. Norton. The book outlines 12 common tactics he’s identified that politicians regularly employ to butcher science, including “the Cherry-Pick,” “the Literal Nitpick,” and “the Oversimplification.” Cat Lazaroff ’89 caught up with Levitan, who lives outside Philadelphia with his wife, Jamie, to talk about the book.

Cat Lazaroff: How did Not a Scientist come about?

Dave Levitan: The idea for the book arose while I was on staff at FactCheck.org in 2015, where I was tasked with explaining why politicians were getting science wrong. I started to notice pretty quickly that there were patterns—that many politicians were using the same rhetorical devices, or making the same mistakes, if we’re being charitable, over and over. I thought it could be useful to gather all these devices and tactics in one place, so we could really see what politicians are doing when they talk about science.

CL: What’s the most egregious anti-science tactic you’ve uncovered?

DL: The obvious answer is the last tactic [I talk about in the book], “the Straight-Up Fabrication,” but that’s actually not that interesting—even though we’re seeing more and more of it these days, from President Trump. The tactic I find absolutely offensive to my core, because it undermines the public’s faith in science, is “the Ridicule and Dismiss.” Politicians use “the Ridicule and Dismiss” to get throwaway laugh lines, and then they try to eliminate funding for foundationally important scientific research. This has taken the form of Mike Huckabee laughing off the effects of climate change as a “sunburn,” or Rand Paul joking about fruit fly research into healthy aging as it relates to the flies’ sex lives. Some of this research, like that funded by the National Institutes of Health, for example, is the reason we now live 30 years longer than we used to. But if politicians can make the public think of research in ridiculous terms, they won’t support it.

“The Certain Uncertainty” is also egregious because it feels so silly to me: We don’t know everything, so we should do nothing. It’s a bit of misdirection based on a misunderstanding of how science works. Obviously we act on uncertainty all the time. It’s like the quote in the book from [cognitive scientist and psychologist Stephan] Lewandowsky, who observes that saying we shouldn’t act on climate change because of uncertainty is like driving 80 miles an hour into a brick wall, because you might not die.

CL: You mentioned that President Trump uses a lot of “Straight-Up Fabrication.” Do you wish you could have included more about him in the book?

DL: I wrote this well before our new president was really on the radar. The book is about the more subtle ways that politicians get science wrong, and those can be tough to see through. But what Trump says is not remotely subtle, there’s no nuance to it. He’s just saying demonstrably untrue, ridiculous things. I’d rather focus on the examples that are useful, that require more debunking than just saying “this is absolutely untrue.” But some of his cabinet members—Scott Pruitt, Rick Perry, for example—the things they say would have fit right in. So while Trump himself isn’t really worth debunking, he’s changed the landscape in such a way that there’s a lot more to debunk.

CL: Do you worry the book might be seen as partisan?

DL: To say that one party gets it wrong on science more than another isn’t really taking a position or a stand. It’s just stating a fact. Some people might say that’s a partisan statement on its face. But there is objective truth out there. And if one party is consistently on the wrong side of that objective truth, it’s not partisan to say that. Plus, the book isn’t just about Republicans. Democrats are among those who get the science wrong about GMOs, for example.

CL: What did you learn at Haverford that helps you now?

DL: At Haverford, I sort of sat on the fence for a while—I couldn’t decide between physics and English. Eventually, I couldn’t do the math for physics, so I settled on English. But all throughout Haverford, there was definitely an appreciation for scientific rigor.

If there was a Haverford professor who was really inspiring to me, it would be my physics professor, Jerry Gollub. He could explain a scientific topic in very easy-to-understand ways. And even though I didn’t go into science, I did go into scientific journalism, where there’s an urgent need to explain very complicated things in simple ways.

CL: What’s next for you?

DL: For the next little while, of course, I’ll be promoting the book. At the March for Science on Earth Day, at a teach-in ahead of the march, I talked about sniffing out these sorts of errors and generally bad science communication, along with a co-speaker who talked about how to encourage good, effective communication.

CL: And what do you hope people will take away from that, and from the book?

DL: I would hope that people maybe just have a little bit of increased skepticism when it comes to listening to political speech. Even when politicians sound convincing, when it comes to science, it’s pretty easy for them to dance around the facts, to sound right when they’re not.

The concepts that I try to get across are relatively universal. Many of these tactics have been used over time by both parties. Any time there’s a special interest group, there will be a politician twisting science to help that group. It could be the oil industry, or a certain constituency in rural Iowa. My hope is that if I can spread the word about the consistent ways that science gets misused, people will be more likely to try to hold their politicians accountable. Calling out these rhetorical tricks is a first step.

People tell me the book sounds very relevant today. There does seem to be a pretty sustained and dire attack on science in general. I hope the book can provide a little ammunition against that attack.

Find out more at davelevitan.com

Cat Lazaroff is managing program director for Resource Media, a nonprofit communications group that works with foundations and other partners to advance public health, conservation, and social justice issues. She interviewed Charles F. Wurster ’52 about his book DDT Wars for the fall 2015 issue of the magazine.