PROFESSOR'S NEW BOOK USES LETTERS TO EXPLORE THOUGHTS OF LOCAL QUAKER ABOLITIONIST

Details

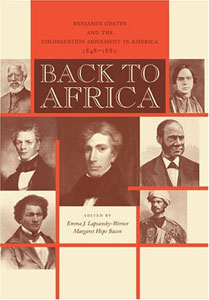

In the sunlit office of Professor of History Emma Lapsansky-Werner, on the third tier of Magill Library, Benjamin Coates seems to belong. Coates, a Quaker wool merchant and cotton fabric maker from Philadelphia and sometime officer of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, keeps watch from a portrait in the center of the wall, his face forever unlined, his gaze quiet and unflinching, a smile never quite moving beyond the corners of his mouth. It's this same visage that graces the cover of Lapsansky-Werner's new book, Back to Africa: Benjamin Coates and the Colonization Movement in America, 1848-1880, co-edited with author and Quaker historian Margaret Hope Bacon and published by Pennsylvania State Press in November.

The book offers new insight into the ideas and intellect of one of the most well-known white advocates of African colonization in 19th-century America, and part of a group of leading abolitionist thinkers that included Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the first black president of Liberia; Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the first black woman newspaper publisher in North America; Henry Highland Garnet, a militant and outspoken black agitator for African American justice; and ex-slave and orator Frederick Douglass. At the heart of the work is a collection of more than 150 recently recovered letters, both written by and to Coates between 1848 and 1880.

Coates was first brought to Lapsansky-Werner's attention when her former husband, who is chief of research at the Library Company of Philadelphia, was asked by the Philadelphia Museum of Art to appraise a collection of letters being offered for sale. In December 1998, Lapsansky-Werner asked President Tom Tritton for money to purchase the letters, emphasizing Coates' Haverford connections (he is the brother of Joseph Potts Hornor Coates, who graduated from Haverford in 1836, and the uncle of four subsequent Haverford alumni), Quaker roots, and membership in the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society.

The owner of the letters, a descendant of Coates, had offered them to other cultural institutions.“But he decided that Haverford would do the best job of preserving them,” says Lapsansky-Werner,“and making them available to scholars.” What Haverford owns is only a subset of the total correspondence; other missives about Coates' business and economic dealings reside with his descendant. Haverford's share is now part of the College's Quaker Collection, and soon after acquiring the letters, Lapsansky-Werner received a contract from Penn State Press to produce an edited volume of the correspondence.

She finds Coates fascinating in the sense that he was“a product of his time, ahead of his time, and, simultaneously, an anachronism.” He was caught up in the major discussion of the era—slavery—and was also concerned with what might happen to African Americans once they were no longer slaves. Yet, he was behind the times because, says Lapsansky-Werner,“he was never able, as others such as Jarrett Smith and William Lloyd Garrison were, to imagine African Americans as his intellectual, political, and social peers.” Coates viewed slavery as a moral evil and wished for its end, but he didn't believe African Americans could reach their full potential in a society that would limit their opportunities.

One of his solutions to this dilemma was colonization in Africa.“He was unable to grasp the fact that Africa was not a place for many former slaves to ‘go back to,'” says Lapsansky-Werner.“Most of them had been born in this country.”

The least generous interpretation of his motives argues that Coates wanted access to inexpensive cotton in Africa without the violence of slavery plaguing his conscience, yet Lapsansky-Werner believes he had two more unselfish goals in mind:“First, to assist African Americans to gain power, dignity, and economic freedom, as well as to obtain, without guilt, the supplies to pursue his own trade. He was definitely conscious of the first goal, but might not have expressed the second in such bald terms.” Coates outlines his plans is an 1858 pamphlet,“Cotton Cultivation in Africa,” which the Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College has put online to support the new book.

To gain support for his position, Coates wrote to many African Americans who were involved in the abolitionist movement, tailoring his argument to suit the individual recipient. His relationships with black people were varied. Many, such as Frederick Douglass, were put off by Coates' ideas, viewing them as self-serving and narrow-minded. (In a long letter to Douglass, Coates took issue with Douglass' resistance, noting that he (Coates) wanted only to have former slaves acquire the same opportunities Douglass himself sought after leaving the South.) However, with Joseph Jenkins Roberts, Liberia's black president, Coates maintained a cordial, mutually supportive friendship.“They were co-conspirators in this project to get African Americans to Liberia,” says Lapsansky-Werner. She states that Coates also“intellectually seduced” many black newspaper writers, including Mary Shadd Cary.

The letters that comprise Back to Africa were annotated over the course of three summers by Haverford students trained in History 361,“Seminar in Historical Evidence,” which requires them to analyze documents from the College's Special Collections.

“They did most of the editorial detective work,” says Lapsansky-Werner who, along with Bacon, guided the students—Marc Chalufour ‘99, Benjamin B. Miller ‘01, and Meenakshi Rajan ‘00—as they tracked documentation, researched the correspondents, and provided footnotes.

The book opens with an introductory essay by Lapsansky-Werner and Bacon that places the letters in the context of the times. It examines 19th-century Quakerism in Philadelphia, the Atlantic-rim economy, African American abolitionist thought, and the nagging question of what should become of freed slaves. Originally there had been two separate essays, with Bacon addressing Coates' family and Meeting life and Lapsansky-Werner discussing the African American community. At the publisher's suggestion, Lapsansky-Werner blended both of these writings into one unified piece.

Because not much has been written about Coates in the past, Lapsansky-Werner hopes this book will contribute to a multifaceted, in-depth portrait of the man—something with more dimensions than the one hanging on her office wall.“Coates had a nuanced, sophisticated mind, and a quite powerful foundation in Quaker morality,” she says.“He could be reduced to an image of a man self-absorbed, pompous, and deaf to others' perspectives, but that would not do him justice.”

— Brenna McBride