A Place for the Uninvited?

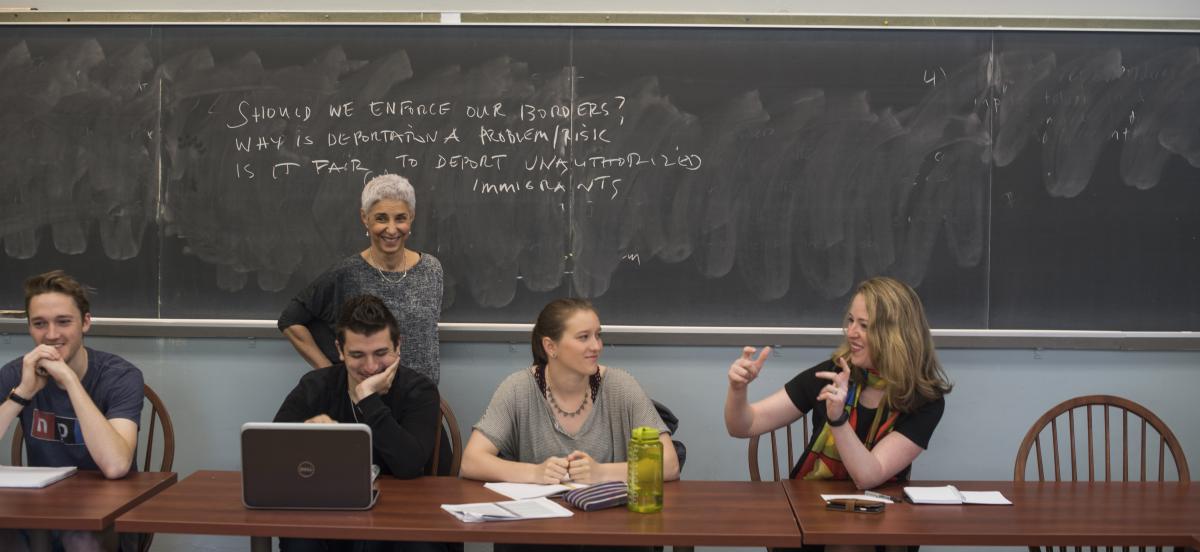

Benjamin Collins Professor of Social Sciences Anita Isaacs (standing, left) co-teaches a new political science course "Refugees and Forced Migrants" with former Deputy Homeland Security Advisor Amy E. Pope '96 (right). Photo by Holden Blanco '17.

Details

Exploring thorny questions about immigration, forced migration, and globalization.

The student grasped the benefits of immigration to the United States—in the abstract, at least. But when it came to his own work prospects in a country of more recent arrivals, millions without legal status, he wasn’t so sure.

As visiting assistant professor of writing Nimisha Ladva waits for her first-year writing seminar “Immigration and Representation” to begin on this spring morning, she recalls how a class discussion unfolded a few days earlier.

I see that it is good for the economy, the student said. But when I show up for a job, and there are people competing with me, then I’m a little more nervous.

“I thought that was a very good point,” says Ladva, who was born to Indian parents in Kenya, grew up in England, and came to America with her family when she was 12 years old. Now a U.S. citizen, Ladva explores some of these pivotal issues of immigration through the solo shows she writes and performs. Uninvited Girl, her most recent work, tackles racism, her family’s temporary status in America as investors in a chicken restaurant franchise, and a fickle system that threatens deportation and then leaves her own and her family’s fates in the hands of a so-called hanging judge.

“It was an interesting conversation,” Ladva continues, “because even if in your heart you are pro-whatever, if it starts affecting you personally, that’s something to think about.”

Outside the classroom, such measured discussions of immigration seem in short supply. With President Trump promising to build a wall at the U.S.-Mexico border, the increasingly polarized discourse often starts and ends with oversimplified dichotomies: Immigrants good, wall bad; immigrants bad, wall good. As Paulina Ochoa Espejo, a Haverford associate professor of political science who teaches a course on the topic, puts it: “When it comes to borders, immigration and citizenship, discussion often sheds more heat than light.”

But step back from the rhetoric, and the central questions of the immigration debate turn more nuanced. Who should come into a country? Why do nations need borders? How should they be enforced?

Dig deep and solutions to America’s immigration concerns appear more achievable. At the very least, an approach steeped in critical thinking allows for the start of serious, fact-based conversations that strive to understand these issues roiling the country.

Remy Erkel ’20, one of Ladva’s students in the writing seminar, advocates for completely open borders. It is a radical opinion, but Erkel, who is from Pittsburgh, uses facts to argue vigorously. Most Latin American immigrants are less likely to commit a violent crime than native born Americans, he says, citing a New York Times article, and adds that immigration actually expands job opportunities for all—a point most economists confirm.

“Before this class I would say I was mostly ill-informed about the immigration debate and about the experiences of immigrants,” Erkel says. “The class gave me the perspective necessary to craft an informed stance regarding immigration.” Most eye opening, he adds, are the personal stories he has read. “It’s much easier to advocate for subhuman treatment of people whose experiences you have never encountered.”

According to those paid to teach and think about these things, to better understand immigration issues, turn to history, both within the United States and around the globe. Consider perceptions of race and culture. Acknowledge the costs of sudden economic downturns and globalized economies on blue-collar industries. Recognize the conditions of poverty and violence around the world, and Central America in particular, that force so many to flee. And so on.

"I think of the immigration conversation as this knotted ball of yarn,” Ladva says. “Every time you pull one string, it pulls other things knotted and tied to it. You try to undo that, but then it affects this other string. I think the effort to simplify is a detriment to both sides.”

On the blackboard in Hall Building, three questions set the tone for the day’s discussion in the course “Refugees and Forced Migrants.”

Should we enforce our border? Why is deportation a problem/risk? Is it fair to (not) deport unauthorized immigrants?

“Deportation may not be an effective method of enforcing the border because people are going to try to return,” says Anita Isaacs, the Benjamin Collins professor of social sciences. She co-teaches the new class with Amy E. Pope ’96, a visiting assistant professor of political science. The two created the course in response to a worsening refugee crisis, one that saw a record 65.3 million people displaced in 2015 alone, according to the United Nations.

An expert on Guatemalan politics, Isaacs outlines for the students the struggles deportees face when returned home: large debts to smugglers, few employment opportunities, and social and cultural dislocation.

“There are all sorts of thorny problems here,” she says.

Pope, who until Jan. 20 was the deputy homeland security adviser under President Obama and holds a law degree from Duke University, retorts: “The costs that have just been described are the costs of someone breaking the rules in the first place, right? … Yes, it’s terrible what people go through. But there are also millions of people who are going through the process and proper channels and waiting years, decades.”

She says she is partly playing devil’s advocate but also pushing students “to really think through … the on-the-ground impact.”

One student contends that deportation “just creates second-class citizens.”

Another says deportation is not intended to deter border crossing but rather to work as an enforcement mechanism that determines who has the right to stay: “Without a form of deportation, we’re saying no matter what you do, if you commit a capital crime, you can stay here.”

Later, Isaacs continues the debate. Her recent research on “unauthorized immigrant” communities, she says, already presages dire consequences of the Trump administration’s hardnosed deportation policy.

Border crossings are significantly down, and farmers from New Jersey to California wonder who will pick ripening crops. The economic implications don’t stop there. The rate of remittances has skyrocketed because many fear deportation and loss of access to bank accounts. Guatemala alone saw a sharp increase in money sent from workers abroad in March, up 18.8 percent from the same month last year for a total of $740 million, according to FocusEconomics.

That’s less hard currency spent in the U.S., and with many fearful to leave their homes, local businesses are taking even more of a blow. Worse, Isaacs says she has heard reports of families afraid to go to the doctor, even to vaccinate their children.

“That will have consequences,” Isaacs says. “It could create a mini health crisis and economic crisis. … Deportation is a blind strategy. We haven’t thought about the repercussions.”

Instead, she argues that the solution is simple, though politically complex: “Create conditions so people want to stay at home, and look at Mexico as an example.” Illegal crossings from Mexico have dropped in recent years as its economy has improved. “You could turn Kennedy’s ‘Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable’ into ‘Those who make sustainable development impossible, make immigration inevitable.’ ”

In February, Pope gave a talk at Haverford on “Migrants, Refugees, and National Security” and emphasized the importance of not alienating groups of people, whether abroad or at home, and thereby fomenting resentment. “I have been up close and witnessed every single piece of this puzzle,” she said. “I’ve taken it apart, put it back together again. … And what I walked away believing quite strongly is that the goal of protecting the United States and the goal of admitting refugees and migrants to our country are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are reinforcing.”

As part of the Obama administration, Pope helped to enforce immigration laws. That meant deportations, earning the president the moniker “Deporter-in-Chief.” Still, care was taken to set priorities, focusing on recent border crossers and convicted criminals, she says.

Not perfect, by any means. “From my point of view, those are all Band-Aids to deal with the significant problem of 11 million in the country without status,” Pope says.

Under the Trump administration, however, that system of priorities has been abandoned. The wider ICE net has caught up people with deep roots here and clean records—except for crossing illegally—Pope says.

“I think that’s bad policy,” she says. “You’re just clogging up the courts with people who are not a threat to anybody, which means then that you don’t have the resources to go after somebody who might be more of a threat.”

Since her days working for California’s Sen. Dianne Feinstein from 2006-08, Pope has supported comprehensive immigration reform “to bring the undocumented out of the shadows” after seeing firsthand that legal channels for farm labor, for example, were not sufficient to meet needs.

Reality also has proven a sobering, if not frustrating, counterpoint to what Nava Kidon ’18, enrolled in “Refugees and Forced Migrants,” describes as her “idealistic view on how the world should handle refugees.”

The political science major with a concentration in peace, justice, and human rights takes issue with the Trump administration’s approach as “both unjust and simply not practical for making our world a better place for all—including Americans.”

At the same time, Kidon, 20, of New York, says she sees “the most critical issue in the current immigration debate as how to balance what is ethical, what is owed to citizens of the world, with what is practical and possible. It’s clear that there’s a huge disconnect between my perspective as a college student who is searching for ways to change the current system and policy makers in Washington who have to ensure that the country is still running tomorrow.”

Europe—as well as the United States—is at a tipping point, according to Alexander Kitroeff, an associate professor of history at Haverford and Prof. Isaacs’ husband.

“We are teetering on whether to accept immigration or actually turn against it,” says the expert on nationalism and ethnicity in modern Greece who teaches “Topics of European History: Nationalism and Immigration.”

“We are in a moment,” he adds, “where we could go either way.”

Which way the seesaw tilts may well come down to the footprint of a newer type of prejudice called “neo-racism.” It is based not on biological differences but cultural ones. In Europe, many observers find the growing tensions over immigrants rooted in the phenomenon, Kitroeff says.

Neo-racist thinking goes like this: “These people come from different cultures, and they are incompatible with us. Therefore, we have to preserve our own culture and exclude them.” Research, he says, shows that immigrants who look like the locals more easily assimilate and gain acceptance.

Similar forces are at work in the United States, though America’s long history of welcoming different cultures has made illegal immigration the primary focus, Kitroeff says.

What’s the solution? Civic education, he says, is crucial to counteract nationalist tendencies. “Countries should explain to citizens that before Turks, we had, in the case of Germany, Polish people working here,” Kitroeff says. “In the case of France, before Algerians, we had Italians and Portuguese.”

In fact, migration—that is, the movement of people—is inherently human, says James Loucky ’73, a professor of anthropology at Western Washington University specializing in the Mayan diaspora.

“We’re bipedal,” says the author of the 2012 book Humane Migration: Establishing Legitimacy and Rights for Displaced People. “Humanity has always been on the move.”

Loucky, who views borders as artificial barriers that divide people, argues that strict enforcement has hampered the natural back-and-forth flow between Mexico and the United States. “We’re creating immigrants out of migrants,” he says.

The economic downturn, Loucky says, coupled with ramped up rhetoric and disinterest in more successful models (such as Canada’s system to assimilate immigrants) “has led to this conflation of immigration with security concerns and crime concerns.”

A stronger border, he maintains, will not create a safer country and solve all its problems. “It is a long-term perspective that we need,” Loucky says. “What does it mean to be a democracy? If we acknowledge that we’re interdependent on other people and ideas, then that gets us beyond these immediacies. … I call it seeing the humanity of migration in the migration of humanity.”

From Visiting Assistant Professor of Political Science Tom Donahue’s perspective, there is another, much-neglected side to see as well—and truly address: globalization’s costs.

Donahue argues that while globalization makes societies richer in the aggregate, its benefits have led most well-to-do people to ignore its real costs—the loss of many decently-paying manufacturing jobs, on the one hand, and skyrocketing wealth inequalities, on the other.

In fact, Trump’s working-class base “feels no one is listening,” he says.

“The central issue of the [2016 U.S.] election was should we go for more globalization,” he says, “or should we try to radically rein it in? And I think it really is a choice. The reason we have these polarized politics is basically because governments and elites in so many societies have not faced up to the costs of globalization.”

Ladva, 47, had never publicly shared her story of immigration until March 2015 at a Freedom Seder, a community event held at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia. “The political climate around immigration became so virulent, [it was] these conversations around ‘these criminals’ and ‘these undocumented,’ ” she says. “It just really bothered me that I was not saying anything when I was part of that group of people.”

Uninvited Girl, an iteration of that first-shared deportation story, was a chance to contribute to the conversation in a way she hoped would make an impact. When she performs the one-woman piece, she takes to the stage with only a wooden chair as a prop. Ladva gives voice to different perspectives: her parents, who got a business visa to invest in a chicken restaurant in 1982; the indifferent immigration officer ready to deport the family a decade later; the “hanging” judge; herself as a college student facing deportation.

“I’m nervous every time,” she says. “You never know what people are going to think.”

In large part, Ladva wants to put a human face on that knotty debate—her own through this intimate play but also any number of other, not-oft-heard immigrant tales that she shares with her students through readings and class presentations.

“One thing we talk about is that all these conversations involve actual people,” she says. “You know? They’re not just statistical problems or policy issues. They’re actual people.”