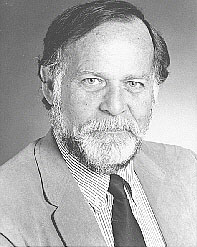

MICHAEL KABACK '59, DEVELOPER OF A SCREENING TEST FOR TAY-SACHS DISEASE, IS ELECTED TO JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SOCIETY OF SCHOLARS

Details

In the early '70s, there were 100 children per year afflicted with Tay-Sachs disease in North America, 85 of whom were of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish ancestry. By the beginning of the 21st century, there were only one or two yearly cases among Jewish youth.

This dramatic decrease is due in large part to the efforts of Michael Kaback '59, a professor of pediatrics and reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego, who was recently elected to the prestigious Johns Hopkins University Society of Scholars. Renowned worldwide as an expert on the treatment and comprehension of Tay-Sachs disease—a fatal genetic disorder in which harmful quantities of a fatty substance build up in tissues and nerve cells in the brain—Kaback developed a test to detect carriers of the Tay-Sachs gene.

Kaback first encountered the disease and its victims as a resident at Hopkins in the late '60s. He was researching human genetic disorders, and had devised a way to test a fetus' probability of developing such a disorder while in utero, using amniotic fluid. In 1969 he became close with the family of a 16-month-old Tay-Sachs patient at Hopkins. Because the disease causes such symptoms as blindness, dementia, seizures, and paralysis, the child would most likely be in a chronic vegetative state by age two or three.“It's a drain on a family's resources and emotions,” Kaback says.“Each day is worse than the day before.”

Around this time, the 10-month-old son of a Hopkins pediatric intern was also diagnosed with Tay-Sachs. The mother was seven months pregnant and now feared that her second child would also be affected. Kaback tested the infant girl shortly after her birth; she was found to be free of disease, and her parents, so mired in anxiety and grief for the past few months, could finally rejoice. Kaback felt that no family should ever be forced to endure this harrowing experience again.

In 1970, he partnered with visiting scientist John O'Brien from the University of California, who had the previous year determined the biochemical cause of Tay-Sachs (insufficient activity of an enzyme called beta-hexosaminidase, or Hex-A). Their goal was to create a simple, accurate blood test that would detect the disease gene in adults and the presence of the disease in early fetuses. Thanks to O'Brien's research, they knew that carriers had less Hex-A in their body fluid and cells than non-carriers, and babies with Tay-Sachs had a complete absence of the enzyme. Because a defined ethnic origin was a factor in the occurrence of Tay-Sachs, Kaback and O'Brien hoped that young Jewish adults could be screened to identify carriers; at-risk couples would then have the option of genetic counseling, pregnancy monitoring, and carrying to term only unaffected fetuses.

Kaback set out to educate the Jewish population about Tay-Sachs, beginning with the Baltimore-Washington area.“It was important not to scare people unnecessarily,” he says.“This wasn't an epidemic—only one in 3,000 Jewish children carried the disease. We just wanted to give them sufficient information so they could make an informed decision.” The educational efforts involved rabbinical leaders, social service organizations, the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, and many others. Studies were conducted to gauge the Jewish community's attitudes toward genetic diseases and the ethical and moral issues surrounding the screening. Press conferences were organized, and the effort was featured in Time and Newsweek.

In May 1971, 1,800 young Jewish adults in Bethesda, Md., participated in the first-ever community-based Tay-Sachs screening. Within two years, similar screenings were conducted in cities across North America, and California began the first statewide program in 1973. The National Tay-Sachs Disease and Allied Disorders Association (NTSAD) has supported the establishment of an international center in San Diego to annually survey worldwide programs in Tay-Sachs screening and prevention and perform quality control assessments of all laboratories involved in screening. This program has also served as a model for the prevention of other genetic diseases in different populations, such as beta-thalassemia in Mediterranean children and cystic fibrosis in Caucasians.“It has implications for many other disorders now that genome sciences are aiding in the identification of many disease genes,” says Kaback.

Although there is still no cure, the incidence of Tay-Sachs in Ashkenazi Jewish families has been reduced by 99 percent.“This demonstrates how one can really have an impact on disease,” says Kaback.

—Brenna McBride