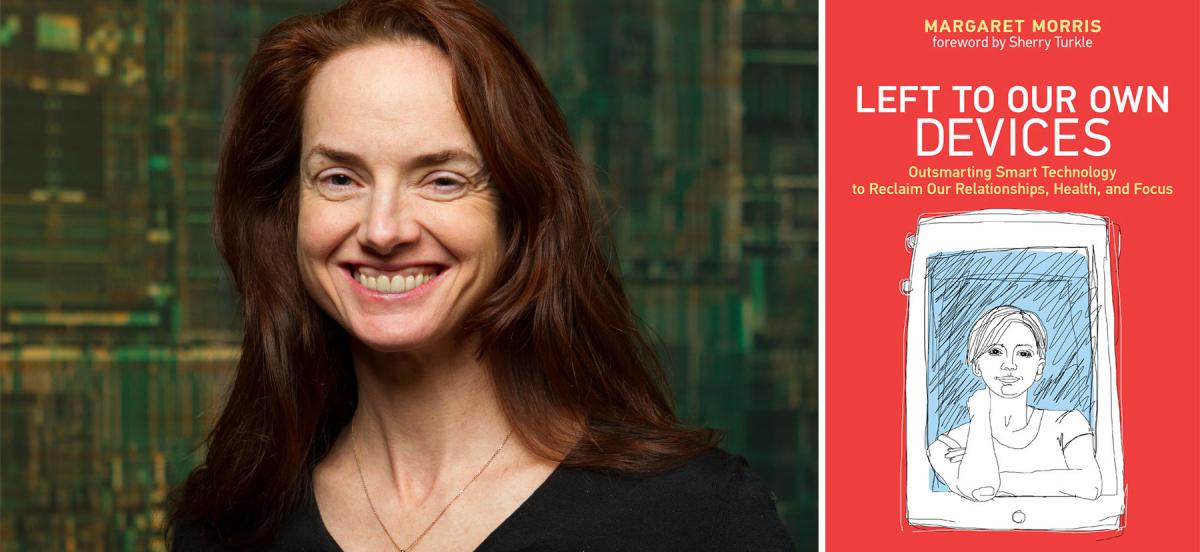

Margaret Morris '90: Outsmarting Smart Technology

Details

The psychologist, researcher, professor, and author discusses her most recent book Left to Our Own Devices: Outsmarting Smart Technology to Reclaim Our Relationships, Health, and Focus.

In the late 1990s, Margaret Morris ’90 was credentialed as a clinical psychologist, but she was troubled by the late 19th-century paradigm of that profession, which is practiced outside the contexts of daily life, and mainly relies on a one-on-one “talking cure” between therapist and client. Looking at the burgeoning tech landscape, Morris began to wonder: What if there were ways new media and emerging technologies could assist people seeking positive change in their lives? So she conducted research on health technology at Intel, consulted for Amazon on people’s experiences with technology, and taught courses with names like “Design and Emotion” at the University of Washington. Most recently, she’s written Left to Our Own Devices: Outsmarting Smart Technology to Reclaim Our Relationships, Health, and Focus (The MIT Press, 2018). The book is the focus of a conversation Morris recently had with journalist Joan Oleck about why we should relate to our iPhones and Androids in a whole new way.

Joan Oleck: I was intrigued by your stories and the quote, “I’ve spent almost two decades talking with people about what they want to change in their lives and how that ties in with their devices.” How does Left to Our Own Devices sum up your research over the years?

Margaret Morris: What I’ve been most impressed by is the resourcefulness and creativity people bring to the way they use technology. That’s what I wanted to showcase, with real examples. So I think Left to Our Own Devices speaks to the strategies that people come up with for taking care of themselves and other people. I think that a certain amount of resourcefulness is required of us—there are a lot of service gaps in mental and physical health care, so I think it’s necessary to be creative. Part of that involves technology, because it’s so woven into our lives.

JO: I loved the stories in the book about people’s uses for technology that the original designers never intended. What were some of your favorites?

MM: One of my favorites was about Jessica, a woman who has struggled with Type 1 diabetes her whole life. It was stigmatizing and required a lot of effort to manage her diet and insulin when she was young; it was a big source of stress. At a certain point, she got a continuous glucose monitor that gives continuous readings to her iPhone and Apple Watch every five minutes. It not only helped Jessica keep an eye on her blood glucose in more of a fine-grained way than she had been able to before, but she also started having more connectedness with her family because she shared the data with them. These weren’t all serious conversations about her health, but also playful teasing prompted by the exchange of data. Another of my favorites was a woman who used Words With Friends, not to kill time but to help a family member who was very socially anxious. If he did come at all to family events, he wouldn’t talk to anyone. So she started playing with him online and could see that he was actually incredibly verbal and eager for contact, but more comfortable in this asynchronous game environment than at family parties. So one of the things she did was start telling other family members about how fun it was playing with him on this game and how good he was. That really changed his status within the family and other people started playing with him as well.Then there was the story of a doctor who practiced primarily by telemedicine. With videoconferencing, she at first just had a blank wall behind her. Then she shifted the camera so patients could see more in the background of her home, and she found that this cultivated greater rapport with her patients: They could comment on the armoire behind her or on the plant. And for a doctor-patient relationship that has a lot of asymmetry, this was a way of bringing in more reciprocity.

JO: The book’s foreword is by MIT Professor Sherry Turkle, who has written about the negative effects of technology use on our lives and culture. But your message about bringing people closer via devices seems the opposite of Turkle’s concerns about the potential for addiction posed by digital devices.

MM: What I’m saying here is that there are some bright spots around how people have used technology to find more intimacy or find insights about their health. It’s those bright spots that I’m hoping will inspire people reading this to think about how they could use technology differently.

JO: Given the advancements coming down the road—artificial intelligence, virtual reality, the Internet of Things, and especially “the cloud”—how do you see our relationships with our devices evolving?

MM: Well I do think our attachment to individual physical technical devices is weakening because of a loose assurance that everything is backed up somewhere. In the introduction, I write about Sherry Turkle talking to someone in 2005 whose Palm Pilot had lost its charge and who said “I nearly died.” I think that reliance on a particular object may continue to weaken. I liked the phrase “left to our own devices,” because it speaks to our strategies as well as technologies like apps and services and data and things like augmented reality and AI that are not necessarily tied to just one device. So, I consider the term “device” in a couple of ways.

JO: Was there anything you studied at Haverford or anyone you knew there that set you on the path you’re on now?

MM: The seminar-style English classes influenced my thinking and interest in stories and critical analysis. Similarly in one psychology class, Randy Milden, [a former professor and dean], once asked what it might mean if a woman wasn’t wearing a watch that she had worn every day for decades. The watch was loaded with meaning for this woman—what Sherry Turkle calls an “evocative object.” My interest in our attachment to objects may have been sparked in that discussion and in many of my literature classes at Haverford and Bryn Mawr. It became clear as we analyzed texts that things that could be considered trivial—for example, a scarf or some other possession—were often very significant. I became intrigued by our relationship to clothing, the environments in which we live, and the technologies that are woven into our relationships.