An Interview With President Thomas Tritton

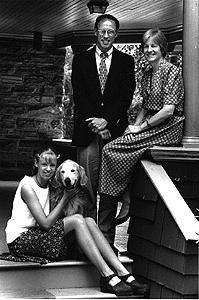

Haverford's 12th President Thomas R. Tritton, wife Dr. Louise Tritton and daughter Christiana. Eldest daughter Lara lives and works in Minneapolis.

Details

TOM TRITTON, his wife, Louise and their daughter, Christiana arrived at One College Circle in early July. Ever since, Haverford's new president has been meeting with alumni, board members and friends of the college. On campus, he has been getting acquainted with the students, faculty and staff as well. In the classroom, he and assistant professor of biology Jenni Punt have also been co-teaching an inter-disciplinary course to juniors and seniors on biologically significant research.

Most of your career has been spent at larger institutions. What attracted you to a smaller liberal arts college?

I went to a small college myself (Ohio Wesleyan University) and decided to go to graduate school so that I could be qualified to teach at a similar institution. I have always understood that liberal arts colleges are one of the nation's treasures and truly nurture lively minds in students. Large universities attempt to replicate the exhilaration of the small college experience, but, because of their size and commitment to so many different programs, such universities can't really offer the intense learning and discovery opportunities of the liberal arts college. The 25 years I spent at two large research universities were productive and rewarding, but I am now very happy to be returning finally to my roots in a small college.

What are some of the challenges facing you and Haverford in this upcoming year?

I'm spending a considerable amount of time listening - to faculty, students, staff, alumni, board members, corporation members and other friends of the college. I have a deep respect for the strengths that already exist here, and through this listening and learning process I hope to synthesize a shared vision of where the college sees itself going.

One of the most important ways this will be accomplished is through the accreditation process the college is currently undergoing. Accreditation - actually re-accreditation - occurs every ten years and is based on a comprehensive self-study. Through the self-study we will examine the mission, the goals and the directions that the college community envisions for the future. This process will engage all campus constituencies, and I have found a high degree of interest in the prospect of taking a close look at ourselves. Some of the issues are the curriculum and its relevance and adaptability; affordability and the cost of higher education; the importance of diversity in the educational process; the essential value of technology; and interdisciplinary approaches to problems that lie outside or between the traditional academic boundaries.

As part of the Middle States evaluation's self-study, I want to ask the college community - students, faculty, staff and administration - to try to envision a successfully diverse community and to articulate their own vision of what that would be. I firmly believe that diversity is everyone's responsibility, and that everyone needs to be involved. Haverford continues to strive to attract students and faculty of color to the college, but being a diverse community isn't just a numbers game. It's much more complicated than that, and I think the college community will need to share ideas and be thoughtful about the way we can approach this vision.

What is the status on plans for a new facility for the sciences at Haverford?

Another major thrust is the planning and implementation of new science facilities. Long before I came to Haverford, there was widespread recognition of the need to renovate and modernize the existing science facilities. Through a comprehensive planning process, the community came to realize that a single integrated facility would best meet the needs of future learning, teaching and research. Although we are still in the preliminary stages, the current plan envisions moving chemistry, physics, biology, math and psychology into a single complex that will be built off Sharpless and Hilles Halls. This will be the biggest capital project the college has undertaken in its history, but it is essential in order to sustain the scientific excellence that already exists here. In addition, the promotion of interdisciplinary work in the sciences can serve as an inspiration and model for similar endeavors in the humanities and social sciences. I am very enthusiastic about the science facility planning, involving all the diverse elements on campus so that we can reach a collective definition of how our intellectual community truly serves our needs and goals.

Most of your career has been spent at larger institutions. What attracted you to a smaller liberal arts college?

I went to a small college myself (Ohio Wesleyan University) and decided to go to graduate school so that I could be qualified to teach at a similar institution. I have always understood that liberal arts colleges are one of the nation's treasures and truly nurture lively minds in students. Large universities attempt to replicate the exhilaration of the small college experience, but, because of their size and commitment to so many different programs, such universities can't really offer the intense learning and discovery opportunities of the liberal arts college. The 25 years I spent at two large research universities were productive and rewarding, but I am now very happy to be returning finally to my roots in a small college.

What are some of the challenges facing you and Haverford in this upcoming year?

I'm spending a considerable amount of time listening - to faculty, students, staff, alumni, board members, corporation members and other friends of the college. I have a deep respect for the strengths that already exist here, and through this listening and learning process I hope to synthesize a shared vision of where the college sees itself going.

One of the most important ways this will be accomplished is through the accreditation process the college is currently undergoing. Accreditation - actually re-accreditation - occurs every ten years and is based on a comprehensive self-study. Through the self-study we will examine the mission, the goals and the directions that the college community envisions for the future. This process will engage all campus constituencies, and I have found a high degree of interest in the prospect of taking a close look at ourselves. Some of the issues are the curriculum and its relevance and adaptability; affordability and the cost of higher education; the importance of diversity in the educational process; the essential value of technology; and interdisciplinary approaches to problems that lie outside or between the traditional academic boundaries.

As part of the Middle States evaluation's self-study, I want to ask the college community - students, faculty, staff and administration - to try to envision a successfully diverse community and to articulate their own vision of what that would be. I firmly believe that diversity is everyone's responsibility, and that everyone needs to be involved. Haverford continues to strive to attract students and faculty of color to the college, but being a diverse community isn't just a numbers game. It's much more complicated than that, and I think the college community will need to share ideas and be thoughtful about the way we can approach this vision.

What is the status on plans for a new facility for the sciences at Haverford?

Another major thrust is the planning and implementation of new science facilities. Long before I came to Haverford, there was widespread recognition of the need to renovate and modernize the existing science facilities. Through a comprehensive planning process, the community came to realize that a single integrated facility would best meet the needs of future learning, teaching and research. Although we are still in the preliminary stages, the current plan envisions moving chemistry, physics, biology, math and psychology into a single complex that will be built off Sharpless and Hilles Halls. This will be the biggest capital project the college has undertaken in its history, but it is essential in order to sustain the scientific excellence that already exists here. In addition, the promotion of interdisciplinary work in the sciences can serve as an inspiration and model for similar endeavors in the humanities and social sciences. I am very enthusiastic about the science facility planning, involving all the diverse elements on campus so that we can reach a collective definition of how our intellectual community truly serves our needs and goals.

When did you first become interested in science and why?

I have been interested in science for as long as I can remember. In grade school I read every book in the library on astronomy. Later on in high school, I discovered the joys of chemistry; and in college and graduate school, I was infected with the excitement occurring in the biological and life sciences. Nothing is more fascinating and captivating to my imagination than solving problems. I think it was inevitable that I would spend much of my life in pursuit of new discoveries and in seeking answers to the many questions that piqued my curiosity

How did you become involved in cancer research?

My career direction was the result of both the times in which I attended college and personal circumstances. I graduated from college in 1969 - the year before the first draft lottery during the Vietnam War. My number in the lottery was 135 - low enough so that I was likely to be drafted. As a result of my Quaker beliefs I applied for and eventually was granted 'conscientious objector' status. My initial assignment for alternate service was as a hospital security guard. Ironically, the job required that I carry and possibly use a gun, so the draft board let me search for other sorts of work.

Eventually, I found a position at Boston University with a researcher who had received a grant from the American Cancer Society. I was very fortunate. During those two years, I gained valuable research experience and was able to continue to work toward my Ph.D. degree.

What is it like to work in the area of cancer research?

I think all the people who are actively involved in cancer research would agree that it's highly competitive, both because it's expensive and because it's challenging. Only 10 to 15 percent of those who apply for funding receive that support. The hardest thing to do in science is to be original. Perhaps this is true in other fields as well, but it seems that true innovation comes from a very small number of people. In cancer research as in most other endeavors, you should be passionate about what you're doing, or you should be doing something else.

Did your research bring you in contact with patients?

During my 25 years as a practicing biomedical professional, I've always worked on problems in the basic science arena, although one of my discoveries could have potential application for the delivery of drugs for treatment of ovarian cancer.

When you're part of a comprehensive cancer center as I was at Yale and the University of Vermont, you are in contact with clinicians and others directly involved with patients, so you're always questioning the relevance of your research. Periodically I went on rounds in the hospital to remind myself that cancer was more than a challenging intellectual problem. Research certainly is interesting and challenging, but it's also much more than that when it comes to the people and families who are faced with cancer as an illness.

In your new role as a college president, will you still participate in the sciences in some way?

Although I won't work in the lab any more, I'm planning to be involved in the science program at Haverford in a number of ways. For example, I'm looking forward to teaching biology. While I was at Yale, I team taught a course with a member of the university's law faculty. The course focused on ways in which educated people can understand and act on scientific issues. I would like to develop similar courses at Haverford.

I will also seek ways to be a commentator on developments related to biomedical affairs as well as continue to be a member of an advisory panel of the American Cancer Society. I currently serve on the board of the Fox Chase Cancer Center here in Philadelphia as well. I love my profession and would not want to lose contact with the work nor my colleagues in the field. I also believe that at Haverford, in particular, the president should be an academic leader and should be intellectually engaged with the academic community.

How relevant is science to most Americans today?

I think it's important for people to understand the value, the power, the usefulness and the appropriateness of the scientific method as it applies to their daily lives and decisions. Too often in today's society people make assertions without being able to back them up with evidence. The value of a scientific education even for the 'non-scientist' is in learning that way of thinking. People are always having to make decisions about their personal safety, their surroundings, the environment - a whole host of issues. And many times it's difficult to know the right response, particularly if the scientific evidence available is contradictory.

In addition to your being the senior research officer at the University of Vermont as well as having oversight of computing and technology, you were responsible for the university's performing arts program and museum. Do you have a personal interest in the arts?

I love and have always been involved in the arts, particularly jazz and classical music and the visual arts. In fact, I used to be a professional musician while I was in college, playing drums, singing and writing music. I belonged to two bands: one was called "The Lyres," which was financially successful and performed in night clubs and at other colleges. The other group, "Dust," was quite serious about new music. We practiced a lot, but we rarely performed anywhere. I enjoyed that experience very much and even considered becoming a composer at one point.

I also am very influenced by the visual arts. I think the arts are the most accessible way we have to connect with the tremendous diversity of human accomplishments. Artistic expression is something we can use to celebrate diversity.

When was your first contact with the Religious Society of Friends?

My first day at college I was invited by a classmate to go to a meeting with him, and I've gone ever since. I was - and remain - attracted to Quakerism for two principal reasons. First, the religious practice of Friends is a direct and personal connection to the spirit. I very much like the fact that no intermediaries or interpreters are needed for someone to have a successful religious life. Second, I have always been impressed with the fact that Quakers act and live their lives in ways that are entirely consistent with their stated beliefs. In the language of modern culture, Quakers not only talk the talk but also walk the walk. This translation of faith into practice is at the very center of Quakerism, and I believe this is why the Society of Friends has remained vital for over 350 years.

Has your impression of Haverford changed since the first time you were on campus?

The best characterization of Haverford is that it's a place with a sense of radical optimism. I've found and continue to discover an environment of high morale and esprit here. It's fairly remarkable to find a place where people truly believe in the importance of the institution where they work. People at Haverford like the college; we like the people they work with, and we're proud of its accomplishments. We see a great future for the college and are willing to work together on problems that we identify as a community.

Was that feeling you sensed about Haverford the motivation for your inaugural theme, "Creativity and the Human Spirit"?

I'd given a lot of thought to that because I feel that the inauguration is about the tradition and history of the college as well as all of the people who love this place. The inauguration is not so much about me as about finding ways in which everyone on campus can come together and celebrate Haverford in the week leading up to the actual ceremony.