Haverford and the History of Monopoly

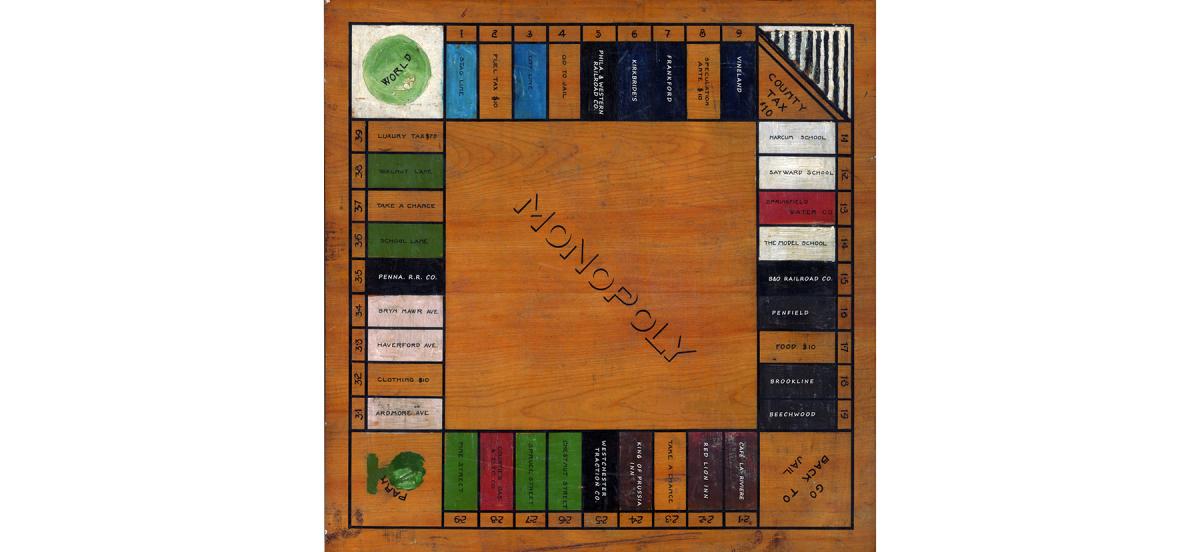

MAde by Haverford students in 1921, this rare example of a "folk Monopoly" game was long thought lost, but resurfaced on eBay.

Details

More than a dozen years before Parker Brothers marketed its first Monopoly board game in 1935, two Haverford College students—who also happened to be brothers—created their own handmade version.

The game featured U.S. presidents as playing pieces, the College’s nearby Walnut Avenue on its wooden board, and “money” made from cardstock once used by the College’s Emergency Unit.

Part of a long history of what are known as “folk Monopoly” boards, the game was created in 1921 by brothers Edward “Ted” Taylor, Class of 1922, and Lawrence “Larry” Taylor, Class of 1924.

Its existence was documented in an entry in the 1924 Record, the Haverford yearbook. And according to an article about the origins of Monopoly by Roy S. Wasserman ’83 that appeared in a 1986 issue of Haverford magazine, that specific mention of the Taylor brothers’ game came to figure as evidence in a trademark infringement lawsuit involving Parker Brothers. But for more than 90 years it was believed that the actual physical game—the board and playing pieces—had been lost.

Not so, it turns out. In 2014, the game turned up in an eBay auction and was snapped up for $3,500 by collector Malcolm G. Holcombe, a Houston management consultant who also owns a first-edition Parker Brothers and other derivative games based on Monopoly.

"I recognized its uniqueness,” he says. There was only one problem: “There was very little provenance on it, which then sent me on a journey to find everything I could about it.”

It took him three years to piece together the game’s history and trace it to Haverford. According to Holcombe, who alerted the College about his find in August, the Taylor board is truly one of a kind. “This is the only known folk Monopoly game board with ‘MONOPOLY’ printed on it,” he says.

And that’s a big deal.

The word is inscribed in black capital letters in the center of the nearly century-old wooden board whose design reflects Philadelphia and the western suburbs around Haverford, including nods to School Lane, the historic King of Prussia Inn, and the long-gone Café La Reviere.

To fully appreciate the significance of the Taylor brothers’ game requires some knowledge of Monopoly’s history.

According to Holcombe, who’s writing a book on the topic, the real estate empire-building game many of us grew up playing is the Parker Brothers board, first marketed after the company bought the patent held by Charles Darrow, a Philadelphian who often gets credit for inventing the game.

But before Darrow’s Monopoly, there was the Landlord’s Game, created by Elizabeth Magie in the early 1900s and first patented in 1904. (Magie was a follower of journalist and economist Henry George, who wrote about poverty and inequality and proposed replacing property taxes on buildings with a land-value tax.) Several years later, Scott Nearing, an economics professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, began using the game as a teaching tool to critique capitalism and monopolies. (His radical political views would later get him sacked from Penn, and he would go on to become a 1960s counterculture icon as the author, with his wife, Helen, of the back-to-the-land bible Living the Good Life.)

Nearing’s use of the game inspired his students to make their own wooden boards, which Holcombe has dubbed the “Wharton Woodies.” Eventually, the handmade, or “folk,” games became known as Monopoly and spread among university students.

One descendant of the Wharton Woodies lineage is the game created by the Taylor brothers, who learned to play Monopoly during the summer of 1920 at their family’s summer home in the Pocono Lake Preserve. Their teacher, according to Holcombe, was Rexford Guy Tugwell, a Wharton School-educated Columbia University economics professor who was staying at a cabin nearby.

Back at school, the brothers, who grew up in Haverford on nearby Buck Lane, got an assist in creating their game from freshman Edwin Rosskam, who did the artwork and lettering on the board. (Rosskam transferred after his first year in order to study art and went on to make a name for himself as a photographer.)

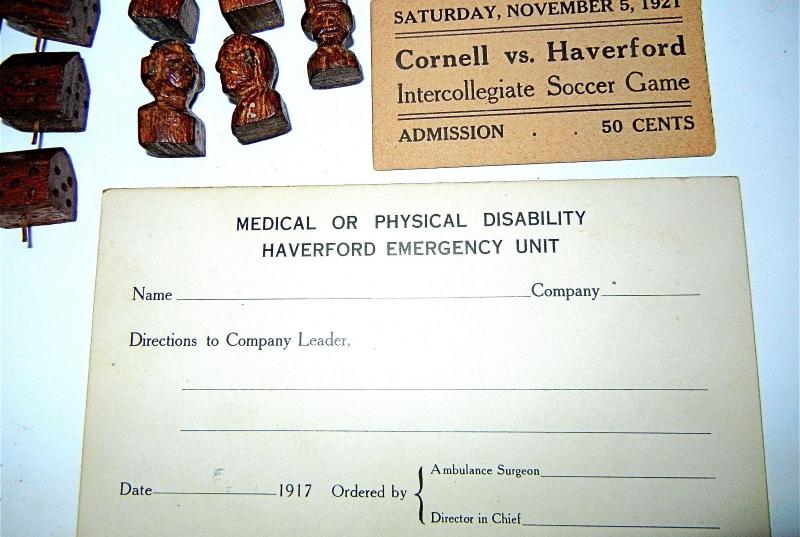

Besides repurposing cardstock from the Emergency Unit (a World War I-era College program that provided non-military support), the Taylors turned the backs of tickets for the 1921 Cornell vs. Haverford soccer game into $100 bills, and also used poker chips as money. Like the presidential playing pieces that included Thomas Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson, the tiny houses used in the game were carved from mahogany by Larry Taylor. He was known as a carver of “men and beasts,” according to that 1924 Haverford College Record item, which Holcombe cites in an article he wrote about the game for the Association of Game Puzzles International Quarterly.

Holcombe, who stores the game in a bank vault, got a break in his quest to trace its provenance when a Google search turned up a 1973 letter to the editor in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune titled “Missed a Monopoly Chance” and signed Lawrence N. Taylor. The letter described the game and noted “the class of 1922 and 1924 at Haverford played Monopoly enthusiastically.... However, other interests took over and I am sorry to say our well-made creation was not preserved.”

Taylor, who died in 1980, continued: “[T]here was talk at the time of patenting the game and either producing it or selling the patent. ... We probably missed something.” (His brother Ted died in 1986.)

Holcombe doesn’t know how the game ended up in the hands of the eBay seller, but everything else he has discovered about the game he has documented on a website.

Why the interest in Monopoly, of all things?

"It’s a passion,” he says. Holcombe and his younger sister played the game for hours. “My mother used Monopoly to keep us children out of trouble.” When his sister was battling cancer in 2012, Holcombe looked to the game as a diversion for her. But he didn’t want to play any old Monopoly. He found the 1961 version—the one he and his sister played as children.

During that search, he discovered much older Monopoly games. “I started researching,” Holcombe says. Once he discovered the existence of folk games, he was on his way.

In 2020, his Monopoly game with Haverford College connections will officially become an antique.

But, he says, “the research has been more rewarding than actually acquiring the game.”