Fords on the Front Lines

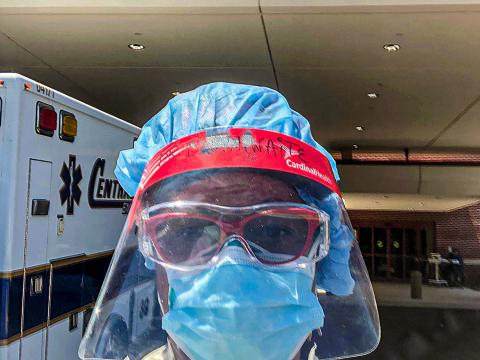

Tiffani Zalinski '04, a critical care nurse in San Diego, is just one of many Fords working on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Details

From medical professionals to public officials, Haverford alumni are dealing with the complex, heart-rending challenges of the pandemic.

In late April and early May, we talked to some of the many Fords on the front lines of the coronavirus pandemic. Working in cities and towns, more than a dozen doctors, nurses, public officials, and mental health specialists shared their experiences dealing with one of the greatest global health crises we have ever experienced.

No matter their job or where they live, similar themes emerged: the short- and long-term effects of dealing with death and dying on such a huge and unrelenting scale; fears about working without proper protective gear; regrets and misgivings about treating a disease that leaves patients isolated and, so far, doesn’t have a cure; helping non-COVID-19 patients in need of care; pandemic politics; and finally, the deadly consequences of the economic and healthcare disparities that have been laid bare by the pandemic.

RISKING THE HEALTH OF HEALTHCARE WORKERS

Marina Zambrotta ’11, who is in the last year of her internal medicine residency at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, treated some of the first COVID patients when they began arriving at the facility in mid-March. One evening she responded to a woman in respiratory distress who urgently needed a breathing tube. When she and other team members asked for N-95 masks to protect against droplet particles, they were told the hospital didn’t have any immediately available. “So we’re all in the room and we intubate her with regular masks on, not knowing if she had COVID.”

It has been a common story of the pandemic. Since the beginning, there’s been an acute shortage of gowns, N-95 masks, and other personal protective equipment (PPE) designed to protect healthcare workers and their patients.

Tiffani Zalinski ’04, a critical care nurse at UC San Diego Health, has become an outspoken critic in local and national media of the lack of PPE.

“When COVID-19 broke out, we noticed that ordinary PPE—gowns, masks, goggles, and gloves—were gone,” says Zalinski. “People were taking it, and the administration was locking it up and telling us we needed permission to access it.” Protocol was confusing, too.

Initially the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) said that healthcare workers didn’t need to wear N-95 masks (which seal tightly and protect against airborne droplets). Wearing a simple surgical mask, they said, was sufficient. “So that’s what we did,” Zalinski says. “In surgery, in particular when we are intubating or suctioning oral secretions, I was doing those procedures every single day wearing a surgical mask.”

After finding National Institutes of Health (NIH) studies that would prove to hospital administrators that healthcare workers needed better equipment, she and other nurses spoke out. “Once there was enough staff who banded together to say, ‘Here’s proof that we’re not safe,’ [administrators] phased in wearing higher levels of protective gear for certain scenarios, like suctioning a patient,” she says.

Will Garrett ’12, who works on a busy COVID floor at a New York City hospital, had similar experiences with lack of PPE. “It just wasn’t available at first, and even when it was, there wasn’t any consistent guidance on how to use it,” says the first-year resident. “I see doctors in other countries wearing full body suits and I think, ‘Where’s that for us?’ Is that an unrealistic dream to think we could have had that level of protection?”

Garrett now wears one N-95 mask his entire 12-hour shift, and has used the same face shield for months, washing it with hydrogen peroxide each day. (The masks have tight seals and are supposed to be changed with each new patient; when worn for hours at a time, they cut into skin and are uncomfortable, and the seal loosens.)

Although the PPE situation has improved, it’s not ideal. “We go patient to patient, and we have to use the same N-95 mask all day,” says Zalinski. “You can go into one room, get viral particles on your face, then go into another room and give it to the next patient. Infection protocols are being ignored because of the supply chain. That’s the bottom line.”

BATTLING THE UNKNOWN

Before this pandemic, infectious disease consultant Joseph Kim ’93 spent his days in a large private practice in Morris County, N.J., focusing on HIV, hepatitis, and inpatient consultations. Since March 15, when his first patient tested positive for COVID-19, he’s spent most of his time at Morristown Medical Center and Overlook Medical Center, helping manage 25 to 40 COVID-19 patients daily on the floors and intensive care units. He didn’t take a day off until May 2.

With no proven medication to treat this particular virus (SARS-CoV-2), it’s been challenging to manage care for patients. “We’re a little limited on what we can do,” says Kim, whose wife is also a physician. The struggle, he says, “has been whether to ‘try’ something. The first rule of medicine is to do no harm, and we are using therapies that have promise but as of yet are unproven. Maybe in a few years we can sift through this information and figure out best practice, but we are improvising to some degree.”

“There’s so much unknown right now,” says David Mintzer ’00, a hospitalist at Denver Health, the city’s big, public, safety-net hospital. (Hospitalists specialize in the general medical care of hospitalized patients.) “The protocols and guidelines are changing almost by the day. We meet every day with doctors across the hospital and we’re learning a lot from each other, comparing what we’ve seen and talking to folks in other locations. But it’s difficult, and sometimes we can’t give patients and families a simple answer. Sometimes the answer is: ‘It’s a new disease, and we don’t know.’”

“You treat the symptoms, but we don’t have a drug that kills the virus,” says Garrett, the resident in New York City. “All of the treatments, initially and now, are meant to dampen the inflammatory reaction to the virus, which devastates the lungs and other organ systems. Mainly it’s giving them oxygen and hoping they don’t spiral.”

DEATH AND DYING IN THE AGE OF COVID-19

In pre-COVID-19 days at the Atlanta-area community hospital where Paula Brathwaite ’94 practices emergency medicine, her department saw one to two deaths a week. After each death, she would conduct a debriefing where staff discussed what went well, what did not, and then expressed how they felt about the experience.

These days there are two to four deaths per shift with no time to talk, and Brathwaite is worried about the future mental health of healthcare workers.

“Codes are happening back to back, and you are too busy trying to clean the room and move on to the next patients,” says Brathwaite, who is emergency services medical director. “Couple that with making sure you are gowned appropriately and worrying that you might take it home, and I think there will be Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) for sure for healthcare workers in the future.”

Matt Wetherell ’12, a second-year family medicine resident at Maine Medical Center in Portland who primarily treats patients hospitalized with other diseases, finds that shifts have become emotionally exhausting in the pandemic. Visitors aren’t permitted in the hospital except in exceptional circumstances, and the result, he says, is that “medical professionals are supporting people who are dying alone, and nurses and other care team members are taking the role of family and being with people in those final moments.”

Wetherell cites an elderly man with (non- COVID related) lung disease who was told he wasn’t going to recover. The patient decided to focus on comfort and gradually come off life-sustaining oxygen support. He asked Wetherell if his wife, two children, and ex-wife could sit with him as he passed away. (Though the man was not tested for COVID-19, Wetherell and his colleagues later determined that it was likely he had the virus and that it had worsened his condition.)

Wetherell talked to administrators but could only get permission for the wife to be there. “I sat with her at his bedside as he passed that afternoon, and it was very sad,” recounts Wetherell, who was on day 12 of 12 straight days in the hospital. “She had to be alone with him, and it was hard not to have additional family there. I found myself wanting to hug her or put my hand on her, but we’ve been strictly told that’s not OK, and I found that really hard, too. While most of us knew to some extent that being around death is part of our work, there’s no way this doesn’t take a toll on people on the front lines.”

MENTAL HEALTH IN THE PANDEMIC

The small, nonprofit clinic where Minneapolis-based social worker Annelise Herskowitz ’12 works sent all its employees home in mid-March, and since then, she’s been counseling her clients via Zoom. “I feel grateful that I’m able to still see my clients, but for some of them, coming to my office was the only time they’d leave the house,” she says, adding that the pandemic and the resulting isolation, loneliness, and fear about health and finances has impacted everyone she counsels. Loss of routine especially affects those already battling anxiety and depression.

Some clients who have lost their jobs are eligible for unemployment, she explains, but it’s not just about the money. She describes one client who lost her job when the business that employed her shut down. “She got a sense of mastery and felt good working there, and she enjoyed socializing with customers and colleagues. Now she’s sitting on the couch for hours on end, and that’s detrimental to mental health.”

These are extraordinary times for all of her clients, says Herskowitz. “I tell them that this is an abnormal thing that we’re going through, and it’s natural to feel scared and lonely.”

INEQUALITY AND THE LUXURY OF QUARANTINE

Perhaps more than any recent crisis, this pandemic has laid bare the immense economic disparities in U.S. society and our healthcare system. Vulnerable populations—lower-income workers, those without health insurance, the homeless, and non-whites—have paid a huge price.

Kiame Mahaniah ’93 is CEO and a family medicine specialist at Lynn Community Health Center, which serves about half of Lynn, Mass., which he describes as “an immigrant-proud and recovering industrial-belt city 10 miles north of Boston. That’s 41,000 people, and all of it’s poor.”

“In the first four weeks, the local hospital, which belongs to a giant in the healthcare industry, tested 500 of its employees, or 12.5 percent of its workforce. The health center was able to test 130 of 41,000 patients, or 0.3 percent. The large company providing our lab services had the temerity to defend its swab distribution as fair, and to say that they were doing their best,” says Mahaniah. “A week later, once The Boston Globe broke a major story on racial inequities in the pandemic response, they were offering the health centers hundreds of tests.”

Nurse practitioner Sarah Taylor ’07 sees those same inequities in the federally qualified health center where she works in a low-income area of Washington, D.C. “The data show that certain communities are being much harder hit than others. Socioeconomic status, race, and access to adequate medical care and preventive care are all factors in peoples’ outcomes.” In Washington, D.C., African Americans are 47 percent of the population but 81 percent of the COVID-19 deaths. “The preexisting health disparities in D.C. have been brought into sharp relief by this crisis,” Taylor says.

On top of that, the majority of her patients can’t shelter at home because they need to work; live in small, crowded apartments; or are homeless. “I had to call a young patient today and tell him his test came back positive,” Taylor says. “When I told him he needed to isolate, he said, ‘I don’t know what you think I’m supposed to do. I have to be at work in an hour, and I need to pay rent.’ ”

At Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, one of the facilities in New York that has been hit hardest by the pandemic, Suhavi Tucker ’12 is dealing with the same issues. “There’s a large immigrant community in Queens, and the hospital is open to all comers, uninsured and undocumented patients, and many of them are deemed ‘essential workers.’ ”

“We’re seeing a lot of delivery drivers and bodega workers who have no choice but to continue working” after testing positive, she says. “Many people continue to work and put themselves and their families at risk”—not to mention the population they’re serving—“but they don’t have the choice to isolate.”

Tucker trained as an internal medicine physician and since last year has worked as a healthcare consultant at McKinsey & Company. The firm allowed her to take a leave to practice medicine full-time during the pandemic. “Vulnerable populations don’t have a voice,” she says. “They aren’t written up in The New York Times, and they unfortunately suffer the consequences.”

PANDEMIC POLITICS

Whether it’s rural Massachusetts, New York City, or Knoxville, Tenn., Fords in government are spending long days battling for resources while balancing demands across the political spectrum that don’t always line up with their philosophy of governing.

“This is about the most intense work experience I’ve been through,” admits New York City Council Member and Health Committee Chairman Mark Levine ’91, who quarantined in early March after coming down with what he believes was COVID-19. “I had all the classic signs: fever, cough, loss of smell and taste, but it wasn’t serious enough to get medical attention, so I rested at home and thankfully got better after two weeks.”

Described by a fellow council member as “the Anthony Fauci of the New York City Council,” Levine’s current obsession is to build a new “public health corps” with the ability to do testing, contact tracing, quarantining, and isolating, “so we can take small steps to reopen the economy. We need to hire thousands of people and have thousands of hotel rooms for people to isolate. We need to increase our testing by 10 or 20 times. And we need financial assistance."

The Haverford physics major says he’s never been more grateful for his science education. “It’s given me a special perspective on this. I think we desperately need to return to the science to understand where this is moving, and what we need to do to fight it.”

Indya Kincannon ’93 was in the fourth month of her first term as mayor of Knoxville when coronavirus struck. “The community really wants a lot of information, and the pressures are to give well-informed responses to this pandemic, which is new to everyone,” she says. “It’s like building a plane while you’re trying to fly it.”

On March 20, she closed the city’s bars, restaurants, and other venues, which was an unpopular decision in her state. “In Knoxville, we’re fighting political tensions and different ideological perspectives on the government’s role in responding. Our county mayor is a former pro wrestler and lifelong performer and a very good speaker, and his ideology is very libertarian. He thinks that the less government, the better. My view is very different. I see government’s role as a social safety net, so even when we have good information on the pandemic, we don’t have a united approach for how to respond to what we know.”

In rural western Massachusetts, Phoebe Walker ’90 coordinates Franklin County’s public health services. Getting PPE has been one of her biggest issues. “No one was ready for the scale and the need, and there are so many people on the front lines who need it, like grocery store employees. There were 800 people in Franklin County with personal care attendants that need PPE, so we connected them to boards of health and emergency management agencies. But it’s complicated.”

In 26 years on the job, says Walker, she’s never worked this hard. “What’s also particularly challenging is that this is a two-part disaster. One part is a terribly devastating disease. On the other hand, everybody’s out of work, people are home with kids, there’s an increase in domestic violence and drug overdoses—this will have a long-term impact on the economy and local businesses. You need different people to respond to these issues, and it won’t be the usual response.”

PROVIDING NON-EMERGENCY HEALTHCARE

Because so many primary and specialty-care clinics and offices are closed, and ER visits for non-COVID issues are down drastically, the disruption to healthcare is potentially as dangerous as the pandemic itself, say public health specialists. The concern is that cancers will be diagnosed later, vaccinations will be missed, and treatment for diabetes, high blood pressure, heart issues and other conditions are being neglected, setting up a second wave of health problems.

In response, many hospitals and medical staff are practicing telemedicine. And some primary care practices have managed to remain open.

Nate Favini ’05 is a primary care doctor with a master’s in public health policy management who works for the San Francisco-based startup Forward, a technology company that runs primary care practices in six cities. He works with physicians, product managers, and software engineers coordinating care in each office.

“We were monitoring news out of China in January and decided to purchase protective equipment for our practices,” says Favini. In February, his company built a coronavirus app so patients could learn more and determine if they should be tested. “It was 14-16 hours a day, seven days a week, from mid-February to mid-March, to make sure our primary care practices could stay open with PPE and protocols,” Favini says. Thanks to those preparations, the practices have been able to treat COVID-19 patients as well as those with other health concerns. Part of Forward’s model is having health professionals available 24 hours a day to answer questions, and they recently launched the equivalent of baseline health assessments that can be done virtually, so patients don’t have to venture out during this pandemic. “The goal is to make high-quality, affordable healthcare much more accessible,” he says.

After being compelled to work without an N-95 mask to protect her, Marina Zambrotta, the Boston internal medicine resident, began to feel unsafe in her job. Then six months pregnant, when she was offered the option to do virtual patient care from home, she took it.

“There are so many patients out there with heart and lung disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes who can’t see their primary care docs,” she says. “I call or do virtual telemedicine visits with older patients, making sure they are OK and safe, and have access to medications. If someone needs a visiting nurse or help at home, we arrange those services, and we can arrange pharmaceutical delivery to their door.”

A LONELY DISEASE

With hospitals restricting visitors in an effort to curb the spread of COVID-19, patient isolation is the worst part of this disease, says David Mintzer, the Denver hospitalist. “Being sick or dying and not having people in the room with you is the hardest thing. Not having family visit you in the hospital until you’re about to die, when we let the rules go, is extremely isolating for patients and families. And we can’t provide the type of care we’re used to giving.”

Doctors and nurses are limiting physical contact with patients, often communicating over the phone through a window or with tablets.

“Unfortunately, we have to limit physical contact because we want to avoid becoming sick, and we need to conserve gowns, gloves, and masks,” Mintzer says.

Tucker, the internist working in Queens, says her goal in the few minutes she’s in a patient’s room is to form a connection. “To keep the risk of exposure low, we try not to enter the room as much, so you have 5-10 minutes to connect, introduce yourself, and explain what’s going on. It’s terrible, but we have to limit harm to other patients. We follow up virtually to answer questions, then we talk to family members over the phone.”

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a doctor, says Zambrotta, “is to sit at the beside and hold a patient’s hand, and you can’t do that now.”

“It’s a lonely disease, and my experience is that it’s lonely for everyone,” says Jeff Nusbaum ’08, an emergency room physician working at several rural Pennsylvania hospitals. “Patients can’t have visitors. We have patients who die by themselves and can’t say goodbye to family.”

Find out more about Haverford graduates who are playing a role in the pandemic in the College’s “Fords on the Front Lines” video series, which features interviews conducted by David Wessel ’75 and Natalie Wossene ’08.