Ford Games: Life Coach

Details

By Kathryn Masterson

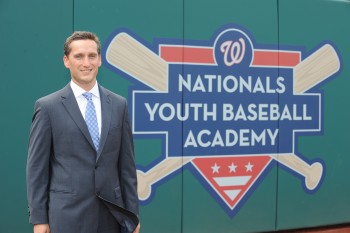

On a warm September day, baseball season is winding down in Washington butTal Alter '98 is just getting started. As executive director of the new Washington Nationals Youth Baseball Academy, Alter, a star shortstop at Haverford who led the team as captain his junior and senior years, is in a hardhat and orange safety vest, driving a buggy on a construction site that will soon be home to coaches, mentors, and 90 third and fourth graders.

The academy will offer programs throughout the year that combine exercise and learning for boys and girls from neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River. At the after-school program, which was scheduled to launch in the fall, students will eat supper, do homework, and play baseball each day. (Girls will be included in those baseball games during the first year; softball will be added as the academy expands its capacity.) The participants, who will be divided into teams of 15, each with a dedicated coach and two assistants, will also take part in baseball-themed English language arts and math/science enrichment and will learn how to cook in the facility's teaching kitchen. Additional volunteers will implement the academic enrichment with small learning groups of three students. Students will continue with the program through high school, with a new class of third graders added each year. Alter says the goal is to grow to 1,000 kids in the first 10 years.

Overseeing construction of the $17 million facility is just a small part of Alter's job. To prepare for the academy's first class, Alter has been building relationships with educators and community leaders, hiring people to help build the organization, and—perhaps most important— working to establish a culture where inner-city kids can flourish while having fun.

It's a new leadership challenge for Alter, but one he has been working toward since graduating from Haverford and going to the Netherlands to play pro baseball. During his year there, Alter worked as a head coach for a team of homesick American teenagers and experienced the powerful effect that baseball—and coaching—could have on youth.

Alter's coaching philosophy—to reward effort and concentrate on personal improvement over game-day results—was reinforced when he and another former Haverford ball player, John Bramlette '00, coached a team of 13-year-olds inWashington in 2001. The team finished the season 1 and 15. But Alter and Bramlette helped the players shift their focus from the games they lost to how much they improved over the season. The boys kept playing together, and four years later, they were beating the teams they had lost to the first year. Two of those players went on to play baseball at Haverford: Gabe Stutman '10, and Alter's brother Jake Alter '11.

The Nationals' Youth Baseball Academy job brings together everything he cares about, Alter says: baseball, education, nonprofit management, and his hometown team.

The academy's fields and classrooms sit across the Anacostia River from the Nationals' gleaming new stadium and will serve children in the city's two poorest wards. The program, modeled after the successful Harlem RBI program in New York, was born out of an agreement between the city and Major League Baseball when the team came to Washington in 2005. Like Harlem RBI, the goal of the Nationals' baseball academy is developing at-risk children's academic and athletic skills to help them grow into thriving adults.

The wards are almost entirely African American, and one challenge for Alter's team will be to make baseball a popular sport. Alter believes a love for the game can be fostered, in part, through connections with Nationals players. Ian Desmond, the team's shortstop and a new father, is an early supporter who has joined the foundation's board.

Unlike achievement in other pro baseball jobs, Alter's success will not be measured in a season's record of wins and losses but in high school graduation rates and“future focus”—meaning the extent to which these kids develop a plan for their future and understand how making good choices helps them get there.

Alter says he learned as a player and a coach to focus on the process—working hard every day to get better—and that is what the academy's coaches will emphasize.

“Our youth will be encouraged to stretch themselves and do things they haven't done before, and they will be celebrated for that,” he says.“It's not a groundbreaking idea, but it's rare in today's youth sports culture, which is focused on winning.”

“Kids are afraid to fail, because they think there are going to be dire consequences,” Alter says. But failing can be the best way to learn and get better, he observes, and youth sports at its best provides a safe place to do that.

It's a philosophy influenced by Kevin Morgan, a longtime Haverford coach who hired Alter as a college student to coach and teach at his Sports Challenge Leadership Academy [see Winter 2010], now led by Jeremy Edwards '92. Morgan remembers Alter volunteering to teach public speaking because he felt he was weak in that area and wanted to improve.

“At a very young age, he got it,” Morgan says. He remembers Alter also projecting an authenticity that is key to working with kids, as well as an ability to take the long view.“I could see he would be a very successful coach if that was something he was interested in.”

After a failed attempt to get a baseball operations job with the Cleveland Indians after college, Alter went to work for nonprofits. He worked for Positive Coaching Alliance, a national nonprofit that aims to make sports a positive experience for youth; then worked in South Africa and Washington for PeacePlayers International, an organization that unites the children of divided communities through basketball. He also earned a master's degree from Harvard's Graduate School of Education, where he was the only non-classroom teacher in his cohort.

Now, Alter gets to build his own organization and set its tone. He already knows he wants the academy to be a place where everyone feels like a leader and shares ownership of its workings and success. It's a very Haverford philosophy, he says, shaped by the experience of living in a community where students get to decide how the college is run.

The new job will also allow him time with the academy kids, contact that typically becomes rarer the higher one moves in an organization. Standing on a half-done field where home plate will be, Alter says he can't wait to play.

“When the facility is ready, I want to be out there taking grounders and throwing balls with the kids,” he says.

For more information about the Washington Nationals Youth Baseball Academy, contact Alter at: Tal.Alter@nationals.com.

Kathryn Masterson, a former reporter for The Chronicle of Higher Education, is a freelance writer in Washington, D.C.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2013 issue of Haverford magazine.