From Deal Maker to Healer

Details

Gerald Levin '60 used to be a master of the universe. The former chairman and CEO of Time Warner had 90,000 people in his employ and a palatial office in Manhattan. A troop of assistants tracked his marathon schedule and private jets and helicopters whisked him to important meetings where he put together billion dollar deals.

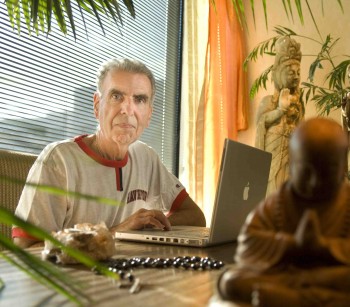

Today the man once known as the most powerful media executive in the world works out of a small, sunny office in a non-descript building in Santa Monica where he answers his own phone. His deal-making days are done. Instead, Levin spends his time helping to mend suffering psyches at Moonview Sanctuary, the holistic treatment center he opened with his wife Laurie Perlman Levin four years ago.

The outpatient facility, which offers confidential services to high-profile clients looking to keep their problems out of the news, emphasizes mind-body health and serves up a blend of Eastern and Western approaches. Along with traditional psychotherapy, the Moonview menu includes yoga, acupuncture, meditation, cranio-sacral massage, neurofeedback and something called equine therapy, which involves getting attuned with a horse. Ceremonial men's drumming circles are a regular occurrence and Levin sits in on every one.

The guy who once swam with the sharks now swims with dolphins and he couldn't be happier.“I'm not the hard-driving executive anymore,” says Levin.“If someone sees me now and we talk, I'm all about emotions and being open. I meditate and run by the ocean every day. I live a very quiet life.”

Levin's departure from the ranks of the corporate titans was a major story when he retired from Time Warner in 2002. He'd worked for the company for 30 years and run it for a decade. He was the guy who predicted the future of cable television, who launched HBO with a hockey game in 1972 and engineered the world's first satellite-TV broadcast (the Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier“Thrilla in Manilla” boxing match). He'd been called Time Warner's“resident genius” and a“media-industry seer.”

Then came the merger between Time Warner and AOL, a move Levin had championed. What was then the largest merger in history quickly became what some have called the worst merger in history. Barely a year in, the merged companies were forced to take a $100 billion loss. Levin's career at Time Warner was over.

But Levin says he'd been contemplating an exit from the corporate world long before then.“It was less related to the ups and downs of Time Warner and AOL than it was to my realizing that I was 63 and I had no belief system,” he says. “When I came out of Haverford, I thought I wanted to be an English teacher. I thought I would go into the world and gather material for the novel I would write or the movie I would make. But somehow I got consumed by 40 years in the world of business.”

It was a growing sense of the briefness and fragility of life that finally made Levin reconsider what he was doing with his own.

In 1997, Levin had endured an unimaginable tragedy. His 31-year-old son Jonathan, an English teacher in a public high school in the Bronx with whom he shared a birthday and a fierce love of sports, was murdered by a former student and an accomplice. The pair bound him in his apartment and cut him with a knife until he gave them his ATM number. After withdrawing $800, they returned and shot him in the head.

“It was the most powerful thing that has happened to me in my life, but instead of taking a lot of time off and trying to understand what it all meant, I started working 25 hours a day and really closed down. I couldn't deal with it,” says Levin.“Then 9/11 happened. Seeing fathers, sisters, sons just going to work one day and losing their lives; seeing the pain and the agony opened the wound of my own son's death.”

On top of all that, his marriage was crumbling and his college roommate, Bob Miller '60, was dying of cancer.“That's when I realized I needed to make a change,” says Levin, who served for many years on Haverford's Board of Managers, including a stint as Chairman.“But I'll tell you something that's curious. In my mind I wanted to return to the state of mind I had when I was a student at Haverford, when I was open to so much philosophy, when I was studying Christianity and Judaism and existentialism. I thought I really needed to take my self back to that person I was.”

His retirement approaching, Levin was still mulling his options when serendipity came calling.

Laurie Perlman, a Hollywood agent-turned-psychologist, had seen a CNN interview with Levin in which he'd talked about wanting to“bring the poetry back” into his life post-Time Warner. A woman who trusts deeply in intuition, she decided he would be a good board member for the holistic treatment center she was trying to get off the ground. So she called Levin out of the blue to ask for a meeting. She wanted to talk about her concept for Moonview, she said, a place she envisioned as“a temple of transformation, about self-love and inner peace.”

“I said this is not in any area that I'm familiar with,” says Levin.“But she said, don't say no. She was very persistent and there was something compelling about the voice.”

Perlman got her meeting. More meetings followed and along the way the two fell in love. After his divorce, Levin moved to California and married Perlman, who claims the ability to communicate with the spirits of the dead.“She calls it soul communion and it's a beautiful thing,” says Levin.

At Moonview, whose interior decor has a distinctly Eastern flavor, no sign on the building betrays the center's presence. Celebrities are whisked upstairs in private elevators and hallways are monitored to ensure that clients never bump into each other.“If you are in the public eye and have some issues that need attention, you need a place to go where you feel comfortable being open,” Levin explains.“Publicity really does not help the recovery process.”

Initially he thought he'd be simply a business advisor, but Levin has come to have an integral role in the center's day-to-day operations. He sits in on intake interviews and takes part in planning sessions where as many as 12 practitioners create individualized treatment plans and review progress. And then there are those drumming sessions.

“Even though I don't have the professional background, I thought I could be of help to people if I use my life as an example of transformation,” Levin says.“I thought that if I somehow made myself available in a very open fashion it would help people to know where I've come from and see where I am now.”

In addition to a steady stream of clients dealing with substance abuse and addiction issues, Moonview, whose fees start at $2,500 for a half-day, also offers a transformational health program.“This is for someone who maybe has had a life altering diagnosis that is affecting their destiny and their family,” says Levin.“In cases like this, there is often not enough attention paid to what is going on emotionally.”

“Then we have a category called“Optimal Performance” which is really designed for CEOs, athletes and performers,” Levin says.“We're trying to get at issues preventing people from operating at their peak. It's kind of preventive mental health medicine. It's to try to help clients get grounded, and integrated and secure in themselves when there is a lot going on.”

Closest, perhaps, to Levin's heart, though, is the center's“Overcoming Personal Crisis” program, designed, according to Moonview's website,“to assist those accomplished individuals in business and other prominent fields, who often work at an all-consuming pace, regardless of the toll it takes on their personal lives.”

“So many of us have this drive for success,” says Levin.“But if it is at the expense of putting your family in the number two position that is a problem. And I'd have to say I wasn't sufficiently present for my family. That doesn't mean I didn't provide for them, but in terms of being there, I don't think I was. It was always about Time Warner.”

“That title, that resume, that business card we use as our identity, that's temporary,” Levin says.“You're going to die, or get fired, or retire. Why not work on understanding who you really are and not get overtaken by all that?”

Levin is increasingly convinced that the testosterone-driven, sharp-elbowed corporate world he once navigated so successfully, must find healthier ways to operate.“We need to bring in the feminine factor,” says Levin.“Management is a humanist art it's not a martial art. It's all about people and caring about people's lives, whether it's who you are working with or who you are trying to serve. If the person at the top believes this, I think companies can change and do well.”

What most delights Levin, whose many gifts to the college include the David Levin Fund for visitors in the Humanities (named for his father) and the Jonathan Levin Scholarship Fund (for his son), is that his new life has indeed connected him to who he once was: that young Haverford student with the questing soul. Says Levin,“I'm seeking my own truth as a 69-year-old, just as I did as a 20-year-old, but it feels a lot better.”

He also sees another echo of Haverford in the meditation practice that has become so important to him.“The Quakers believe that there is a divine light in all of us and that in calm, reflective quiet you can access the divine,” says Levin.“That is basically a form of meditation. It's somewhat amazing to me that after all these years that's what I'm returning to.”

--Eils Lotozo

This article first appeared in the Winter 2009 issue of Haverford, the alumni magazine of Haverford College.