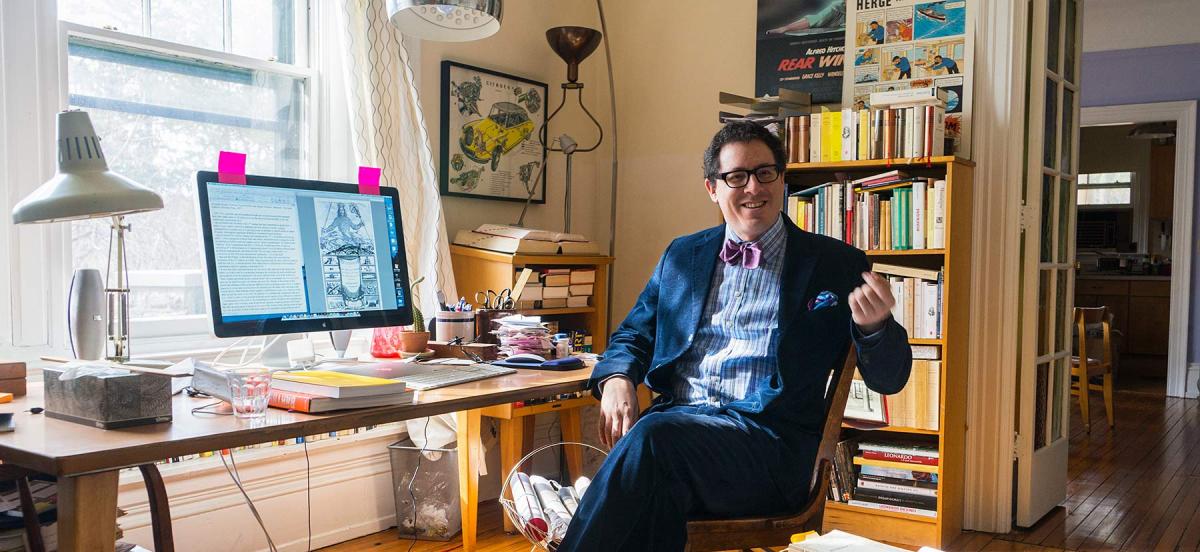

Office Hour: David Sedley

Photo: Patrick Montero

The associate professor of French and comparative literature gives us a tour of his office.

Associate Professor of French and Comparative Literature David L. Sedley teaches French with a focus on the 16th and 17th centuries. His courses typically range from language and literary analysis to seminars on Michel de Montaigne, inventor of the essay, and on Blaise Pascal, who applied mathematics to faith in his Pensées, with an occasional course on Paradise Lost author John Milton.

Sedley, who is well known on campus for his sartorial style, received his B.A. in philosophy from Yale University and a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Princeton University. He is the author of Sublimity and Skepticism in Montaigne and Milton, published by the University of Michigan Press in 2005, and he’s currently at work on a new book, tentatively titled Race to Infinity, which examines the connections between literature and the sciences. “In the research I’m doing, I need to understand numbers, at least in a general way,” says Sedley, “and one of the special things about Haverford is that I can go over to Hilles and talk to a mathematician, or go to a laboratory and talk to a scientist. That’s something that’s harder to do, I think, at a large university, where the divisions between the humanities and the sciences are greater.” Sedley has a small office in Founders, but he works mainly out of a big, sunny, book-lined space in the College Avenue home he shares with his wife, Associate Professor of History Lisa Graham. He also conducts some of his seminars there, gathering students around a big table in the dining room. Says Sedley, “That’s another thing I love about Haverford—that I live right across the street from campus and can do something like that.”

- Photo of Sedley’s great-grandfather and an iron from his tailor shop: That’s him probably in the late 1930s. He came from Russia; he was a tailor, and he had a men’s clothing store in Cleveland. My grandfather and an uncle of mine took it over, and I remember as a kid going down into the basement of the shop, where they had Italian tailors working on the clothes using industrial pressing machines and things like that. That was a formative experience for me, and I think it’s related to some of the things I’m interested in now.

- Citroën poster: In his book Mythologies, which is one of the most famous books in 20th-century French literature and philosophy, Roland Barthes has a chapter on this car, which looks like a spaceship compared to the cars that came before it. He compares it to a Gothic cathedral. He’s interested in how this machine is a work of art. I’ve always been attracted to positions like that, because I’m fascinated by mechanisms and machines and the mathematics that make them possible. I’m interested in the divisions between what used to be called the mechanical arts and the liberal arts, between numbers and letters, and between what are now called the “two cultures” of science and literature. I’m interested in understanding how those distinctions got constructed.

- Catalog from the recent exhibition on Blaise Pascal at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris: I teach a course on Pascal, and one of the things we look at is how in these earlier periods [the arts and sciences] weren’t as separate as they seem to be these days. You have a guy like Pascal in the 17th century who is an important physicist and mathematician. He invents the first calculating machine, which is the ancestor of the computer, and he helps invent probability theory (that’s why I have those dice there). But he also writes literary masterpieces.

- Vintage map of France: This map shows what the different areas of France are about in terms of economy and industries. They’re saying, “Here is fertilizer. Here is oil. There, they have pigs. Here’s tobacco, and lace, and sugar. They’re sending vegetables over to England there, and getting textiles from England here.” A map like this comes out of a French tradition, a way of thinking. How can we take a piece of reality and understand it in a geometrical, mathematical way? It’s kind of a French specialty: How to create an abstract, beautiful version of the truth. The challenge is not losing the truth in the process!

- A few of his editions of Montaigne’s Essais: I have tons of copies of this book. Every time I re-read it for a course, I use another pen to make notes. I began by underlining in pencil and then I go to red pen, then to blue pen, then purple pen. Eventually, I am going to have to start again. Maybe there’s a green pen out there. …

- Image of the staircase in the Château de Chambord: In the early 16th century, the King of France said, “I’m going to hire the smartest person who represents Renaissance culture in Italy, and he’s going to design something for me, and we’re going to start a Renaissance in France.” And so he hired Leonardo da Vinci, who designs this castle and this spectacular double-helix staircase. The staircase is hollow in the middle, so you can climb it and see someone on another part of the staircase, and you think you’re going to run into them, but you never do. I’ve been running around Italy and France studying staircases as part of my research for the book. That’s something that I’m pretty obsessed with—the experience of going up a certain kind of staircase and what that does to the body and what that does to the mind, and how it can evoke a sensation of infinity. It’s kind of a long story. …

- Notes for his next book: You can just open up any page of the notes I take, and it’s going to look like that. This is how I organize my research. You summarize what the book you’ve just read says, and then in brackets, you add your own thoughts. I show students this method. They don’t have to do it exactly this way, but it works as a model for how to organize your thinking. —Eils Lotozo