Wanting to be Wallace Stevens, Getting to Know Philip Roth

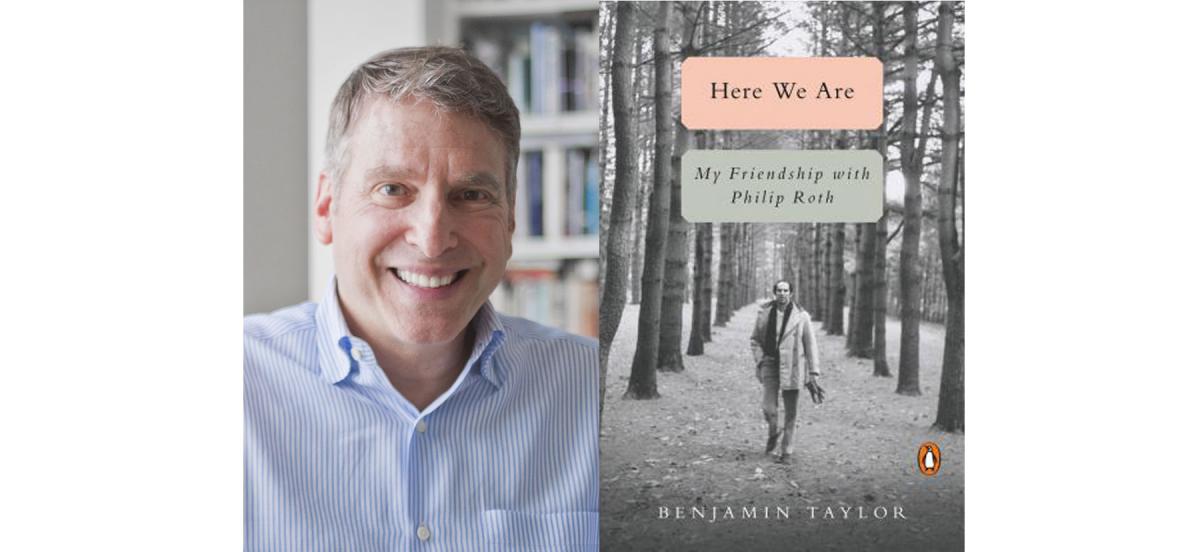

Benjamin Taylor's latest book, Here We Are, a thoughtful and honest consideration of his friendship with novelist Philip Roth, was released in May.

Details

Hilary Leichter ’07 talks to fellow author Benjamin Taylor ’74 about his new book, Here We Are: My Friendship With Philip Roth.

Benjamin Taylor was a philosophy and French major at Haverford, and he’s telling me about the moment his future plans took a turn: “On Barclay Beach I was reading The Portrait of a Lady, and I came to a scene that caused the scales to fall from my eyes, and I understood that I wasn’t really interested in philosophy, I was interested in literature!”

Thank goodness for Haverford and Henry James! Taylor’s Barclay Beach epiphany led him to become a genre-hopping, critically acclaimed novelist (Tales Out of School, The Book of Getting Even), memoirist (The Hue and Cry at Our House), literary biographer (Proust: The Search), and travel writer (Naples Declared: A Walk Around the Bay). And Taylor, who teaches at The New School and Columbia University, has a new book, Here We Are, a thoughtful and honest consideration of his friendship with novelist Philip Roth, which came out in May from Penguin Random House. It’s a beautiful portrait of their relationship, part frank memoir and part deeply felt homage, at once a tribute to and a new tributary flowing toward our understanding of Roth’s life and work.

We spoke over the phone about school, memory, and his unique path in the arts.

Hilary Leichter ’07: Were you writing when you were a student at Haverford?

Benjamin Taylor: I wanted to be a poet—like so many prose writers. I did a private writing tutorial with Jim Ransom. I was entranced by certain American poets at the time. I think I wanted to be Wallace Stevens. You can’t do something like that. The job’s always already taken. It took me a long time to find my own voice, my own originality. I was a critic, and a novelist, and a biographer, and a memoirist, and now I just think of myself as a writer. The genre seems less important than what it is I have to say. A lot of the same energies that go into writing a memoir go into writing a novel, and a lot of the same technical problems present themselves: how to set a scene, how to narrate, how to handle time. All those things pertain to memoir writing as surely as they do to fiction.

HL: There’s a great line in your new book: “Writing a novel makes a god of you; writing a memoir does not.” Can you say a little more about that?

BT: I meant that when you’re a novelist you can make things up, when you’re a memoirist you’re not supposed to.

HL: Do you deal with imagination and fact differently in fiction than in nonfiction, or is it the same no matter what you’re writing?

BT: Well I think it shouldn’t be the same, or else you’ve blurred the boundary. I really believe in the distinction between fiction and nonfiction, but what I find is that when you dramatize the facts, when you frame them in scenes, when you rely on direct speech, you’ve worked a certain alchemy on the bare givens of experience and memory. And let’s face it: Memory itself is a notorious artificer. Memory leaves out, and puts emphasis here, and deemphasizes there. Memory is already art.

HL: There’s a moment in Here We Are where you discuss Lucy Nelson’s death in Philip Roth’s novel When She Was Good, and how it strangely predicted Roth’s wife’s death. Have you ever had the experience of imagining something that then came to pass?

BT: I think all writers of fiction have the experience of writing things that then come to pass. In Tales Out of School, my first novel, I had the eerie experience of writing about someone whose brother suddenly dies; and that subsequently happened to me. Creative imagination has a way of getting things right. Even things that it can’t know or can’t yet know. I guess it’s just because you know something about the fragility of life, that you tell the story in such a way that what’s liable to happen to a fictional character is liable to happen to you.

HL: In Here We Are, you say that “Writers can be sorted into school-lovers and school-haters.” Were you a school-lover or a school-hater?

BT: School-lover. Especially when I got to Haverford. I loved my time there. I still have a fantasy of going back there to teach. It was simply a golden place, and I felt that there was an ethos that must derive ultimately from Quakerism, expressing itself in secular ways. A preference for plain-spokenness. A curriculum grounded in the traditional things done well. The vibrant intellectualism of the atmosphere. You could put your tray down at any table in the [Dining Center] and hear people, despite their youth, talking about the most serious things. They were already adults intellectually, already on high-minded paths. I was well aware that wasn’t the case at all colleges.

HL: You’ve edited two books about Saul Bellow, his collected nonfiction and his letters. If, in the future, you had your collected letters published, is there someone you would want to edit that book?

BT: No, and I wouldn’t want such a book to exist! Are you kidding? I wouldn’t want ever to be the subject of a biography either. I loved what Philip Roth said about that: “Two things await me, death and my biographer. I do not know which is the more to be feared.”

HL: Roth told you: “Your path has been your own.” What does that mean to you?

BT: Either it meant a great deal or nothing at all, and I decided it meant a great deal and was a very fine compliment declaring me a one-off. I haven’t done the customary things. I haven’t become a tenured professor, for instance; I’ve lived half on the inside of academic life and half on the out. And instead of just writing one kind of book—there are people who just write novel after novel—I became interested in all kinds of writing, especially memoir. So, I guess he was right. My path has been my own. This may sound immodest, but false modesty is not among my vices. (I have others.)

HL: How do you think Philip Roth would react to the book?

BT: I never allowed myself at any moment to say, “What would Philip think of this?” because I thought that would be bad for the book. I knew I wasn’t interested in hagiography; I didn’t want to ornament him or sanitize him, or present a different Philip from the one I knew—who was, to speak bluntly, a very mixed bag of a man. I know I’ll have detractors. May critics swarm all over what I’ve written. That’s as it should be.

Hilary Leichter’s debut novel, Temporary (the story of a temporary worker with fantastical and improbable jobs), was published in March by Coffee House Press/Emily Books. She lives with her husband in Brooklyn, N.Y. You can find more of her writing at hilaryleichter.com.