George P. Smith '63 Awarded 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

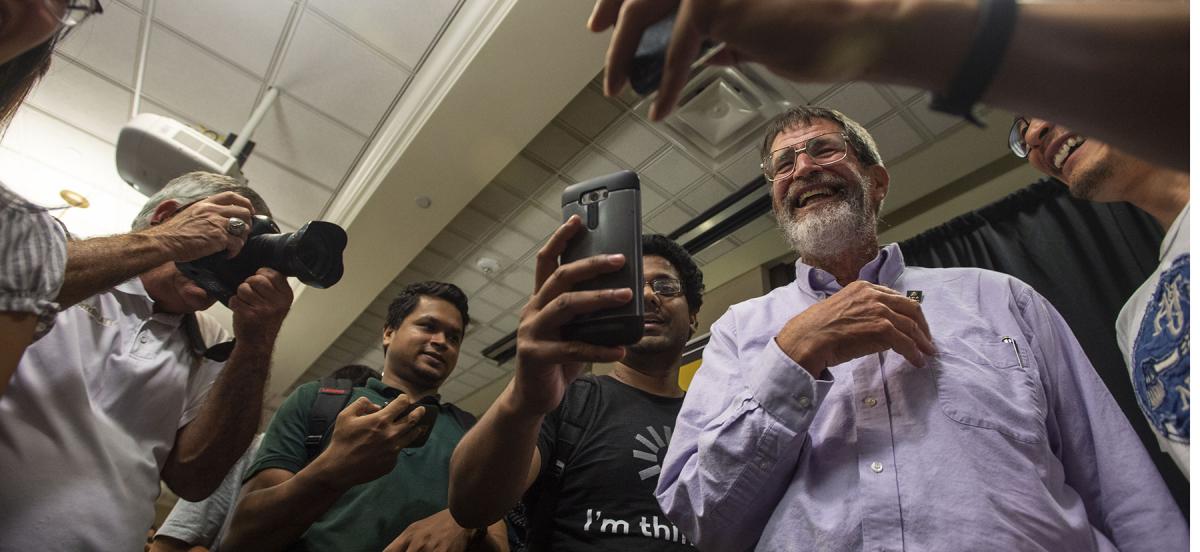

A throng of selfie seekers mobbed Emeritus Professor George P. Smith at an event at the University of Missouri after the announcement of his Nobel Prize. Photo courtesy of University of Missouri.

Details

Smith, one of three Nobel laureates in chemistry this year, is the fourth Haverford College alum to win a Nobel Prize and the second—after Joseph Taylor, Jr.—from the Class of 1963.

George P. Smith '63 was already awake and starting to make coffee in the pre-dawn hours of Oct. 3 when the phone rang. It was 4:30 a.m., too early for a casual conversation.

On the other end of the crackling line was a call from Stockholm telling him he was among a trio of researchers that The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences had awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

For a moment, the 77-year-old Curators Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Biological Sciences at the University of Missouri thought the call was a prank, a common spoof among scientist friends. But the line was too scratchy to be anything but real.

“I kind of knew it wasn’t any of my friends because the connection was so terrible,” Smith recalled with humor. “I mean, Sweden is a really advanced country, but I think they need some work on their phones.”

Nobel officials described Smith’s research as “harnessing the power of evolution,” and it has led to the production of new antibodies used to cure metastatic cancer and counteract autoimmune diseases, among other things.

He shares the prize with two other researchers—Frances Arnold of the California Institute of Technology, who was awarded half of the 9-million-kronor ($1.01 million) prize, and Gregory Winter of the M.R.C. molecular biology lab in Cambridge, England, who splits the other half with Smith.

Smith’s win makes him the fourth Haverford College alumnus to receive a Nobel Prize. He joins his classmate Joseph Taylor Jr., who won the 1993 physics prize; Theodore W. Richards, Class of 1885, who won the 1914 chemistry prize; and Philip Noel-Baker, Class of 1910, the recipient of the 1959 Nobel Peace Prize. In another alumni Nobel connection, Henry Cadbury, Class of 1903, accepted the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, which he helped found.

News of Smith’s prize spread quickly across the University of Missouri campus, where he began teaching 43 years ago, and by late afternoon on the day of the announcement, Smith was on his way to a reception and media event on campus where throngs of enthusiastic students, faculty, and staff mobbed the unassuming scientist for more than 30 minutes. The crowd of more than 300 crammed into the room for a glimpse of the prize winner, and many held cellphones in hopes of shooting a selfie with Smith in the background.

A modest man by nature, Smith reminded the audience that science is a web of ideas and that breakthroughs come as the result of many scientists’ work. “I don’t know if I particularly want to say that I am proud personally of this award,” he said. "I think all Nobel laureates understand they are in the middle of a huge web of science, of influence and ideas, of research and results that impinge on them and that emanate from them.”

Smith acknowledged his work developing phage display, which allows a virus that infects bacteria to evolve new proteins, but was emphatic that he could never have imagined how it would be applied to result in improved treatment of cancer and autoimmune diseases and even to help locate stress fractures in steel.

“I happened to be in the right place at the right time to put those things together,” Smith said. “I am getting an honor that has been earned by a whole bunch of people.”

Smith, who has focused much of his research on the generation of genetic diversity, has authored and coauthored more than 50 articles in top scientific journals, and was selected by the American Society of Microbiology for its 2007 Promega Biotechnology Research Award. He retired in 2015 and lives in Columbia, Mo., with his wife, Marjorie Sable, professor emerita and director emerita of the MU School of Social Work. They have two sons, Alex, a physician, and Bram, a journalist.

Smith was born in Norwalk, Conn., in 1941. As a boy, he was fascinated with the natural world, especially reptiles. His favorites were alligators and crocodiles. His parents were exasperated during trips to the zoo where their son spent hours studying animals that didn’t move.

In a phone interview, Smith said he came to Haverford College as an undergraduate with the idea of becoming a naturalist or herpetologist. “I was very interested in snakes,” he said. But exposure to an exciting new world of science at the College changed everything for him. “I have a mathematical way of thinking and it turned out molecular biology was way more suitable for me.”

Recalling the path that led him from prep school at Andover to Haverford, Smith said it was a family connection that inspired him to pay a visit: His great-grandfather George Pearson was a member of the Class of 1869, “Everyone from my class at Andover went to Yale, Princeton, and Harvard,” he said. “But I went to look at Haverford, and I just really loved it. I didn’t even apply to those other places. Haverford was small and not pretentious. It was just this really warm place that felt perfect for me.”

Before coming to Haverford in 1959, Smith spent a year as an exchange student in England. “I was kind of young for my age and my mother thought it would be a good idea.” There he learned to play cricket and rugby “not very well,” he said. “I was very much not an athlete.” Despite that, Smith played on the Haverford cricket team, serving as captain during his senior year, and still has fond memories of cricket coach Howard Comfort ’24, who was also head of the Classics Department. “He seemed really ancient to me, but it was absolutely incredible how he could hit the cricket ball,” said Smith, who is given to self-deprecating humor and a sincere friendliness that had him lobbing questions at his interviewer about her life. (“I grew up in an army family and we moved all the time, so I learned how to make friends with everyone,” he said.)

Other strong memories of Haverford include a mathematics course with Professor Cletus Oakley. “I think it was called 'College Mathematics' and it was really influential for me,” said Smith. “I had taken a little calculus, but I didn’t have much training beyond that. This was just a lively course, beautifully taught.” Still sounding a little awe-struck, he also recalls a course with Professor of Philosophy Paul Desjardins: “You didn’t call any of the other professors by their first name, but you called him ‘Paul.’ You sat on an Oriental carpet in his living room and had a Platonic dialogue. I thought this was so mature and so French. It just made a huge impression on me.”

As a young man interested in science, Smith began his undergraduate career at a remarkable time. “There was much ferment going on. There were scientific controversies, and people were asking sharp questions that would have been difficult to ask 30, or 20, or even 10 years earlier.” Indeed, it was in the early 1960s that the genetic code was deciphered by a trio of American scientists.

And it was a particularly fortunate time to study biology at Haverford, Smith said. “That was because [biology professor] Ariel Loewy came to Haverford and decided this little, tiny college wasn’t going to cover all of biology. It was going to focus on cell biology, molecular biology, that kind of thing. And he recruited two young faculty members, Mel Santer and Irv Finger. Ariel Loewy was kind of like this prophet figure at the time—kind of larger than life. But all three of them were live wires. This was an incredible department. There were totally devoted to their teaching and also found time to do some pretty good research.”

In particular, he recalls a biochemistry test given by Santer, that asked students to explain the logic of a famous experiment of the time. “I was really excited by that experiment and I thought I got it,” said Smith. “But Mel didn’t think so, and I got pretty bad mark. That experiment turned out to be something I really focused on when I went to graduate school. So Mel lived on in my life and I am really grateful to him. There are times when a teacher does something that can light a fire when the teacher isn’t even aware of it.”

"George Smith represents the best of Haverford," said Professor of Biology Rob Fairman. "His rigorous, forward-thinking, and creative ideas, along with his sense of fairness, integrity and collegiality in his scholarship, exemplifies what we so appreciate of our students' future work."

For his senior thesis project in molecular immunology, Smith’s adviser was a Meg Mathies, a newly minted Ph.D., who’d come to campus as a visiting professor. “We were trying to get at a problem in immunology and that was, ‘How can the immune system recognize almost anything foreign that comes down the pike?” Smith calls his experiment “totally naïve and totally unsuccessful.” (In the next year, the problem would be solved in another, more practical way by Edgar Haber, the scientist who became Smith’s Ph.D. adviser at Harvard.)

"She must have had to grit her teeth," said Smith of Mathies, now a Claremont Colleges emeritus professor. "She probably had to tell herself, ‘These are undergraduates. Just go with the flow.’ But it was Meg who really introduced me to molecular immunology, which was really important in my life up through my first two years at Missouri, before I moved on to other things."

Before he launched his career as a scientist though, Smith, who doesn't remember his fellow Nobel-winning classmate Joseph Taylor Jr. at Haverford, spent a semester teaching in a North Philadelphia high school. He’d been influenced in his senior year by the book Summerhill, about an experimental school in England, and by his experiences at Quaker weekend work camps, he said. “I had total admiration for the people who dedicated themselves to this kind of thing, and I thought, ‘That’s what I’m going to do. But it was too hard.”

So Smith went on to earn a Ph.D. in bacteriology and immunology from Harvard University in 1970. After a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Wisconsin, he joined the faculty at MU in 1975, teaching undergraduate courses and/or labs on biology and genetics, as well as graduate-level courses on nucleic acids, cell biology and molecular genetics, and training masters and doctoral students, as well as post-doctoral fellows. As a teacher, Smith was well known for his hands-on learning approaches and critical thinking skills he instilled in students.

“At Mizzou, I had a tremendous amount of freedom to explore what I think is interesting,” Smith said. “Not all universities give you the freedom to do that, and I think science really depends on that.”