Alisa Roth ’95 Tackles the Tough State of Mental Health Treatment in the Prison System

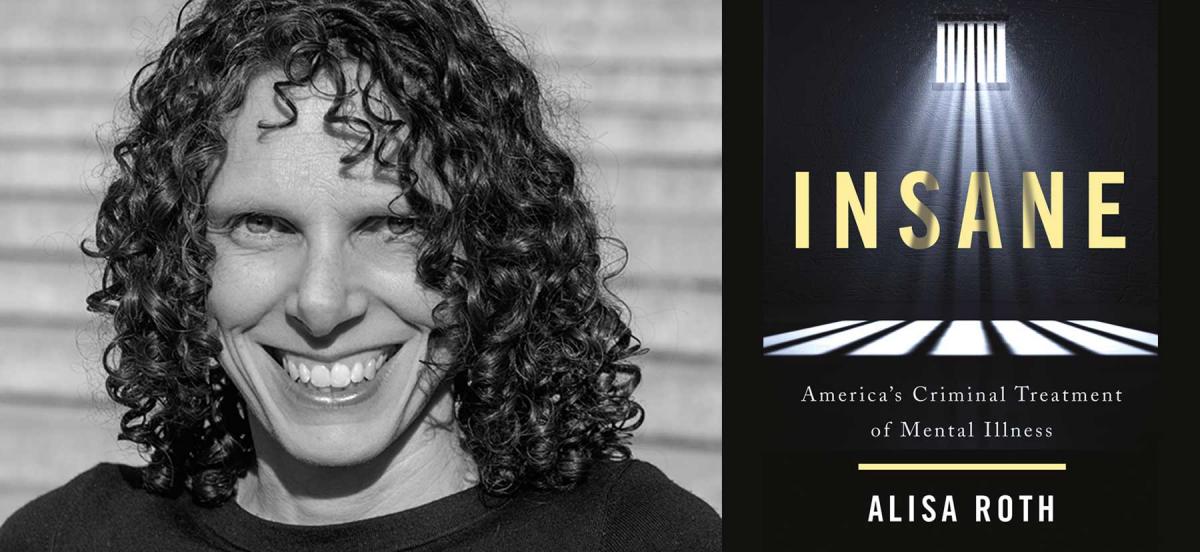

The new book by Alisa Roth '95, Insane America's Criminal Treatment of Mental Illness, is an exposé of the warehousing of the mentally ill in prisons and jails under conditions that squash chances for recovery. Photo by Matthew Septimus.

Details

In her new book, Insane, America’s Criminal Treatment of Mental lllness, Roth explores how mental illnesses are treated in the country’s correctional facilities.

Ever since Alisa Roth ’95 launched her journalism career, she’s made it a point to take on tough assignments.

In 1999, Roth received a Fulbright fellowship to study immigration and asylum policy in Germany. From her base in Berlin, she covered the growing tensions over immigration all over Europe for outlets including NPR and CBS Radio. She later reported on the Iraqi and Syrian refugee crises in the Middle East and Europe. When she returned to the United States, she took on what was arguably an even more difficult and heart-wrenching story—the nation’s sprawling criminal justice system.

In some ways the timing couldn’t have been better. Roth’s reporting began at a time when politicians, public-interest lawyers, and others had begun to raise questions about the nation’s burgeoning prison population and the penal codes that swept into prison a generation of young nonviolent offenders who in years past would have received shorter sentences or no prison time at all.

And with that came another issue. Increasingly, prisons and jails were turning into warehouses for the mentally ill. Roth soon set out to unravel the complex interplay between corrections facilities and the nation’s patchwork and largely inadequate mental health system. Her new book, Insane: America’s Criminal Treatment of Mental Illness, is an exposé of the warehousing of the mentally ill in prisons and jails under conditions that squash chances for recovery.

Hundreds of thousands of prisoners in the United States are mentally ill, and the percentage of prisoners with some form of psychiatric malady is growing, Roth reports. The problem has become so acute that jails and prisons in New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles now constitute the largest psychiatric facilities in the nation, and corrections officials are overwhelmed.

Treatment is sporadic at best, nonexistent at worst. While many in the system are well-intended and try their best, too often mentally ill prisoners live under conditions of extreme cruelty and degradation.

A Soros Justice Fellow, Roth is a former staff reporter for the business and economics-focused radio show Marketplace. She is a frequent contributor to NPR programs, and her work also has appeared in The New York Times and The New York Review of Books. Roth, who lives with her family in New York, spoke to Chris Mondics, the former Philadelphia Inquirer legal affairs writer, about her book.

Chris Mondics: How did your Haverford education prepare you for a career in journalism?

Alisa Roth: It was amazing preparation. I was a history major back when they still did the ["Seminar on Historical Evidence"] history project, so basically what would happen is you were given either an object or a document and very minimal information about it, and you had to figure out what it was and write a thesis on it. My object was a snuffbox from Namibia donated by a previous history major. That was one of my first real reporting experiences. I didn’t know at the time that it was reporting, but it absolutely was.

CM: How else did your undergraduate years play into your career?

AR: The Quaker values at Haverford really followed me, this sense of wanting to bear witness and sense of duty to do that. I feel very strongly the responsibility for sharing what I see and using my place of privilege to talk about it.

CM: What is it that inspired you to write about the mental health crisis in the nation’s prisons and jails?

AR: I’ve always been interested in the underdog; I’ve done a lot of reporting on refugees in the Middle East and undocumented immigrants and underprivileged communities in the U.S. People with mental illness who end up in the criminal justice system—it just doesn’t get more underdog than that.

CM: Did you have difficulty gaining access?

AR: It was literally all over the map. In some places I got spectacular, unfettered access and in other places, I was shut out. While the courts are completely open, the jails and prisons are really closed because the states and counties and wardens keep them closed; it makes it easy for them to hide all sorts of things.

CM: When you did get access, did you get a realistic view of life in the institution, or a version sanitized for the press?

AR: For the most part, there is no sanitized press version, because press is rarely allowed into these institutions. The real challenge is getting in—in some cases it took months of negotiating, even with the help of doctors and other people on the inside who wanted me to see it. Sure, I always assume that wardens and corrections officers are on their best behavior when I’m there, but the truth is that it would be hard to hide the fact that a facility smells terrible or is falling apart, or a prisoner who is banging his head on the door or screaming at something nobody else can see.

CM: On the occasions when officials cooperated, why do you think that happened?

AR: The reasons varied a lot. There were officials obviously who felt that they were doing the best that they could and were proud of what they were doing. And maybe they wanted to call attention to this mandate that they had been given. The Cook County Jail in Chicago fits that model. The sheriff invited journalists in to see the extent of what he had to deal with.

CM: The problem of prisons essentially warehousing mentally ill prisoners dates back a long time, since the nation’s beginning. Are we really any better off now than during Colonial times?

AR: Yes, in the sense that we have a better understanding of what causes mental illness and how we treat it, but I think there is something really wrong if we are still locking people up with mental illness because we have nowhere else to put them.

CM: If you had a magic wand, what would you do to fix the system?

AR: This is the multibillion dollar question. We need to start with the mental health care system and make access more available and more consistent. So much of the problem could be avoided with effective community care. On the criminal justice side, we need to stop locking so many people up—so much could be avoided by sending people to treatment instead of to jail. If we do a better job treating people on the inside and then connecting them with care once they have been released, we would all be better off.