Collection Favorites: Travel diaries

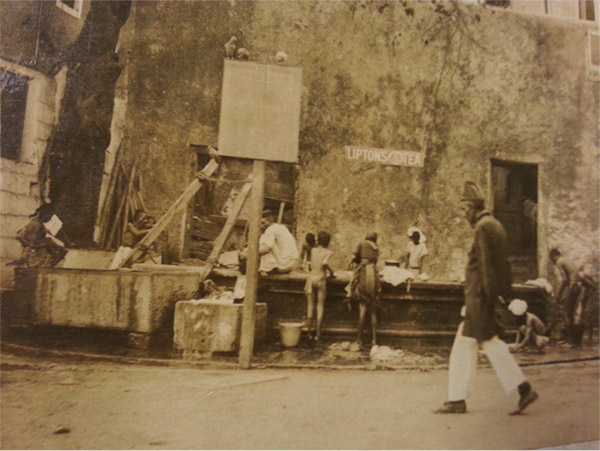

A photo from Margaret JenkinsÍ diary, taken during her time in Bombay (1911)

Details

The first in a series of news articles in which Kara Flynn highlights some of her favorite materials she has been working on this year in Special Collections.

In the next few posts, I want to highlight some of my favorite materials from the collections I've been working on this year. I work with such a vast number of items that it is easy to forget some of the really cool materials I've worked with over the past eight months. Many of my "favorite" materials only stay my favorites for a few weeks, so when a certain collection continues to stand out for me after a few months, I figure it's worth writing about.

For those of you who may not know, Quakers got around. Many Quaker ministers traveled not for pleasure, but on "religious visits," which is essentially Quaker-speak for mission trips. However, religious visits were often not as focused on conversion as the traditional understanding of mission trips might imply. Rather, many religious visits focused on strengthening ties between Quakers around the world-- ministers would travel to other Quaker meetings, visit with Quaker families, and do some missionary type work, such as visiting Quaker schools (particularly those set up for native groups or the poor), and visiting prisons. During these travels, Quaker ministers, both men and women, often kept travel diaries. The travel diaries in our collections have been some of my favorite materials to work with, for a variety of reasons. Travel diaries cover so many topics--they not only shed light on the realities of travel in the past, but they also reveal the political and cultural tensions that arise when someone is thrust out of their comfort zone and is confronted with heightened racial issues, cultural differences, language barriers, and their own understanding of themselves and the culture they come from.

One of my absolute favorite travel diaries is that of Margaret Jenkins. I came across her two volume travel diary, "A Visit to the Himalaya Mountains 1911-1912," back in October, and it still stands out to me as a wonderful example of the richness of travel diaries as primary source materials.

The diary opens by giving some background concerning why Jenkins made the trip. Jenkins' second cousin, Samuel E. Stokes Jr., had lived and worked with lepers in India for many years as a young man. While working to distribute funds for earthquake relief in Kangra, India, Samuel contracted Typhoid, and was taken to Kotgush, in the Himalayan Mountains to recover. Samuel seems to have become quite attached to the community in Kotgush, and after his recovery, he became the headmaster of the "C.M.S. school for boys" there. After a number of years, Samuel comes to the conclusion that in order for him to more successfully convert the community to Christianity, he should marry a local girl. A marriage is arranged between Samuel and a young woman whom Jenkins calls "Agnes Benjamen," although, I have to just point out here that I highly doubt that a young woman in the remote Himalayan Mountains in 1911, who spoke no English, went by the name "Agnes Benjamen." In any case, Margaret Jenkins sets off for India, to act as a companion to her cousin, Samuel Stokes' mother, so that the two might meet Agnes, and show their support of the marriage.

The two volumes of Jenkins diaries offer so much material to dig into that I doubt I'd be able to cover it all in a post, but I will try to highlight the aspects I found most interesting. The travel itself is worth commenting on. It takes the pair of travellers a little over a month to arrive in Bombay (now Mumbai). Tracking their progress across the map, they leave from New York and travel to Madeira, Gibraltar, Algiers, Marseilles, to Port Said, down the Suez canal, through the Red Sea, across the Arabian Sea, and finally to Bombay. Once in Bombay, the pair had to make the overland journey to Kotgush (now Kotgarh), which even today takes a little over thirty hours to drive. The logistics of making such a trip are impressive, to say the least.

While Jenkins is generally eager for new experiences, it is interesting to watch her move further and further outside of her comfort zone. Her experiences on board the various ships definitely expose her to more diversity than she is used to-- she regularly comments on the various kinds of people she meets onboard, included, but not limited to, people from Italy, France, England, India, Northern Africa, Spain, China, and New Zealand. She often comments upon their mannerisms and style of dress, though she does have some substantive conversations with her fellow passengers as well. One that particularly stood out was a discussion she had with two women in New Zealand (the first country to extend the vote to women) concerning women's suffrage there. While Jenkins' exposure to diversity is important, she generally keeps to the kinds of people (i.e. white, Christian, women) that she would have spent time with at home, and she expresses some very problematic views on race, which would take so much time to unpack that I cannot cover it in this post.

These issues are further heightened in Jenkins' interactions on land. While she often mentions having positive interactions, particularly with women in both North Africa, and in India, she always seems to end with an assertion of their difference. After one such interaction with two young women in Egypt, she concludes the paragraph with "of course there was the evil smell of the east in this old quarter."

During her time in the Himalayas, Jenkins spends a significant portion of her time visiting with Agnes and her mother, though the women don't share a common language. Towards the end of her trip, Jenkins concludes that Agnes "was just like the normal young girl in U.S.A." This conclusion brought up a number of issues for me. I can understand that spending over a month with another person can forge a bond, regardless of the language barrier, and I can also understand that as a religious person, and as someone who cares very much about her cousin, Jenkins would want to be accepting of Agnes. Perhaps, the fact that Agnes has converted to Christianity helps Jenkins to come to terms with the marriage. And it does seem as though, despite the ongoing racial and cultural tensions, that Jenkins truly enjoys spending time with Agnes. I also have to acknowledge, however, that it is possible Jenkins can feel this way because she knows that Samuel and Agnes will never have to be integrated into Jenkins' own community in Philadelphia, and will continue to live out their lives in a remote Himalayan village after she leaves. Jenkins will never have to confront these tensions in her day to day life after the trip is over. Additionally, I find the conclusion Jenkins makes problematic, in that it erases Agnes' unique cultural identity by asserting that she is just the same as any girl in the U.S. I understand that Jenkins writes this out of a desire to accept Agnes, but erasing their differences robs Agnes of her own experiences, just as calling her "Agnes" does.

While it would be easy to come to the conclusion that the racial, cultural, and political tensions in historical travel diaries are relics of the past, reading Jenkins' diaries made me realize that tourists today often say and thinking similarly problematic things. One could, for example, draw connections between the history of the tensions Jenkins' diaries reflect, with the tensions that we see today with modern tourists, particularly when tourists visit third world countries. For example, for me, this brought to mind issues surrounding volunteer tourism and slum tourism in the third world. Just another reminder of the way in which historical primary sources continue to be relevant in modern issues and conversations!