The First Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies

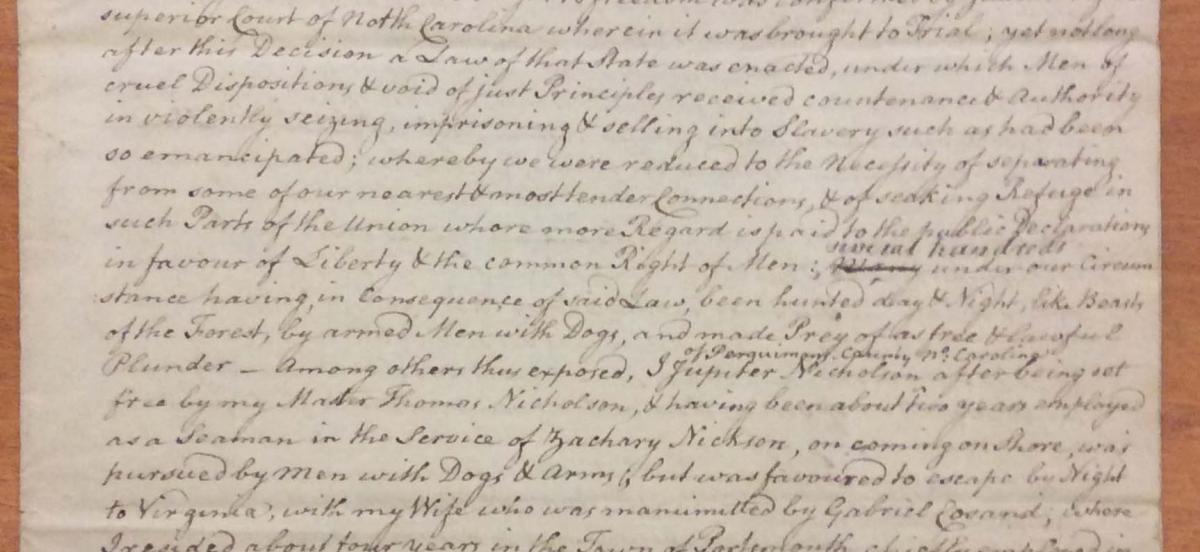

The first page of the petition.

Details

Newly uncovered evidence from HaverfordÍs Quaker and Special Collections reveals that a 1797 petition was an early example of interracial abolitionism, a trend historians typically associate with the period after 1830.

In January 1797, four former slaves submitted the first petition from African Americans to Congress. Job Albert, Thomas Pritchet, Jupiter Nicholson, and Jacob Nicholson recounted that they had been freed by Quaker slaveholders in North Carolina, but armed men had tried to capture and re-enslave them. Eventually they had fled to Philadelphia, but remained vulnerable under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. In fact, they described the plight of another unnamed ñfellow blackî formerly enslaved in North Carolina who was languishing in the Philadelphia jail as an alleged fugitive slave. Congress refused to act on the petition, but scholars have long recognized the importance of this petition in the history of black resistance and antislavery. However, they have known very little about its creation and assumed that white abolitionists declined to aid the black activists. Newly uncovered evidence from HaverfordÍs Quaker and Special Collections reveals that the 1797 petition was an early example of interracial abolitionism, a trend historians typically associate with the period after 1830.

I came to suspect that Quakers were involved in the petition after finding evidence at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania that some Friends aided black activists in the creation of a second petition to Congress in 1799-1800. The Quaker activists were members of the Philadelphia Meeting for Sufferings (PMS), an organization that Friends had established to promote pacifism during the Seven YearsÍ War, but which soon expanded its activism into the realm of antislavery. While writing my dissertation at the University of Virginia, I used the microfilmed version of the PMSÍs formal meeting records but found no references to the black petitioners. The silence struck me as suspicious, so I eventually made the trip to Haverford to examine the PMSÍs rough minutes and miscellaneous papers.

At Haverford I soon found the type of ñsmoking gunî evidence I was looking for: an excised portion of a PMS letter to North Carolina Quakers explaining that they had encouraged four former slaves to petition Congress. I was then fortunate enough to receive a Gest Fellowship to continue my research the following year. Hours of digging in the PMS papers revealed not only additional excised passages from other letters and reports about their collaborations with the black activists, but also a rough draft of the January 1797 petition. (The draft petition escaped previous notice from scholars presumably because they did not know to look for it and because it was mislabeled ñ1801?î and thus misfiled.)

Revisions to the draft petition reveal some new details as well as insight into the thinking of the black and white activists who collaborated on it. For instance, whereas the final draft refers to an anonymous ñhumane personî who secretly transported Job Albert out of North Carolina, the initial draft identifies him as Caleb Trueblood. Trueblood was a member of the North Carolina Standing Committee, the southern equivalent of the PMS. He was also the former master of Moses Gordon, the unnamed ñfellow blackî described in the petition as being in jail. Another revision to the petition clarified that the ñexilesî were not only ñlate Inhabitantsî but also ñnativesî of North Carolina. This change highlighted the African AmericansÍ birthright connection to the nation in order to buttress their right to petition Congress for redress of their grievances.

The House of Representatives eventually caved into southern pressure and dismissed the petition, but interracial abolitionism persisted. In the winter of 1799-1800, PMS members helped Job Albert, Jacob Nicholson, and sixty-nine other black activists organize a second petition to Congress. This form of collaboration across racial lines contradicts the typical characterization of Quaker abolitionists as conservative during this period, and indicates a need to integrate the PMS into the history of antislavery.

-- Nicholas P. Wood

Nicholas P. Wood is a former Gest Fellow at Haverford and currently the Cassius Marcellus Clay Postdoctoral Associate in Early American History at Yale University. His research on the 1797 petition appears in: Nicholas P. Wood, ñA ïclass of CitizensÍ: The First Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies,î William and Mary Quarterly 74 (January 2017).