A Cognitive Neuroscientist in the Classroom

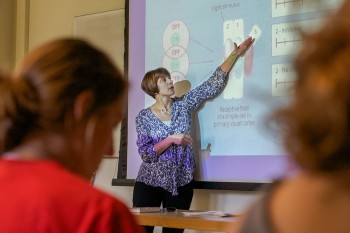

Professor Rebecca Compton teaching psychology.

Details

Haverford prides itself on outstanding teachers. That means it's no easy task to garner attention. In the packed classroom of“Cognitive Neuroscience,” Professor of Psychology Rebecca Compton routinely puts her skills as a standout—correction: reluctant standout—on full display.

On a recent day, the recipient of the 2012 Lindback Distinguished Teaching Award clicks through a PowerPoint presentation on the intricacies of brain processes, specifically the retinal ganglion cells involved in visual perception.

Hands flying, she lectures at a Mach 5 clip. Compton, 42, is eager to pack as much information as possible into 90 minutes. But even as she unravels complex details about gray matter and how it's used to make sense of the world, she happily slows her pace to engage students in discussion, delve into curious case studies, or grab attention with optical illusions.(In one slide, a green, black and yellow flag transforms into Old Glory.) Always, she peppers her lectures with“Does that make sense? Any questions?”

“Becky has a really amazing ability when interacting with students to build you up and make you feel really good about yourself and your work, even as she's guiding you,” says Emily Dix '12, a psychology graduate who worked on her senior thesis project with Compton.“She makes her students feel like collaborators. She's a role model for me.” Dix took Compton's“Foundations of Psychology” to fulfill a social science requirement and was so smitten she decided to pursue psychology as a major. Along the way, Compton became a favored professor.“I would love to emulate the way she interacts with students, to have that knowledge of the field,” Dix says.

Wendy Sternberg, a professor of psychology and former associate provost, describes her colleague as“incredibly modest.”

“If you look at her record, her accomplishments are stellar,” Sternberg says.“She's a prolific researcher. She teaches material that really makes students think about themselves. She has a revolving door for students in her office.”

A self-described teacher-scholar, Compton is an authority on understanding how the brain detects an error of judgment. She is widely published, has been awarded several National Institutes of Health grants, and co-authored the text Cognitive Neuroscience, used in her course. Compton, who recently attained full professor status, knows her material inside out and wants to impart that expertise—as well as passion for her subject—to her students.

“People are naturally interested in understanding themselves and also how other people think and behave and why they do the things they do,” she says.“Students are naturally drawn to the topic of psychology.” In true Haverford fashion, Compton deflects attention away from herself and onto her students.“They are working on the production of real scholarship,” she says. Senior thesis projects regularly result in publications in peer-reviewed journals, notes Compton, who views her role as mentor.“I really enjoy that process— brainstorming with students and trying to engage in that discovery of ideas with them as they ask questions.”

Compton grew up in central Pennsylvania and studied at Vassar College. She intended to pursue clinical psychology, but a course on“Sensation and Perception” captured her imagination.“I took the class mainly to fulfill major requirements but found myself unexpectedly fascinated by the mechanisms of the brain's sensory and perceptual systems,” says Compton, who completed her doctorate in biopsychology at the University of Chicago.“The idea that we could try to understand how the brain actually works, including the mechanisms that explain our everyday sensations, perceptions, thoughts and actions, was riveting to me.”

At Haverford, her cognitive neuroscience research—an increasingly hot area of study—has focused on a particular aspect of what's known as executive function, the brain's way of regulating behavior.

“There's a lot of unknowns in how the brain functions, especially at a higher cognitive level,” she says. Compton and her students are teasing out some answers.

Simply put, she explores how we detect errors. Studies with an electroencephalography (EEG), using a skullcap that records the brain's electrical activity, have shown that when an individual makes a mistake—and realizes it—a particular brain wave spikes. Compton is interested in factors that might influence the peak's magnitude and implications in other contexts.

One experiment investigated the correlation between error detection and daily stresses. What Compton was trying to find out:“Do people who are better able to detect performance errors, who have more pronounced peaks, also show more adaptive control of behavior in other situations?”

The answer appeared to be yes. The study found that those better at detecting errors were also better at handling life's downs—a potential window into the workings of depression.

Compton's research, though, comes with its share of challenges.“We have to make sure people make enough mistakes to have enough data to look at. That can be challenging, particularly with our students.”

It seems the subjects—those brainy Fords—get it right 90 percent of the time.

Lini S. Kadaba is a writer based in Newtown Square, Pa., and a former staff writer at The Philadelphia Inquirer.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of Haverford magazine.