Translating the Unprintable

Details

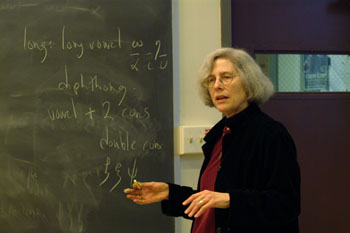

Translation is always a tricky business. No two languages divide up the world in quite the same way, and cultural differences can introduce distinctions in one language that are absent in another. Those distinctions are at the heart of the work of Haverford College Professor of Classics Deborah Roberts, who has won a grant from the Loeb Classical Library Foundation to pursue research on the translation from ancient Greek and Latin into English of a very particular kind of language: obscenity.

“If the translator's own culture considers the explicit obscene,” says Roberts,“the translator is likely to encounter a taboo that complicates the translatability of the work in question.” Though there may be equivalent terms in the target language (the language the work is being translated into), she says, those words may be ruled out by social constraints or legal rulings.

“In this project I'm planning to continue an exploration I recently started into the effect of shifting attitudes towards the obscene on the translation of ancient literature,” says Roberts, who has already begun work on the topic in the form of an article,“Translation and the ‘Surreptitious Classic': Obscenity and Translatability,” in A. Lianeri and V. Zajko, eds, Translation and ‘The Classic': Identity as Change in the History of Culture, Oxford University Press, 2008. (During the early stages of research on this project Roberts had the help of Willy Lebowitz '08, a Hurford Humanities Center Research Assistant during summer 2006.)

Of particular interest to Roberts: the diversity of translators' approaches in both expurgated versions (those with objectionable parts removed) and unexpurgated versions of ancient texts.“I'll be looking especially closely at the 19th and 20th centuries, a period when constraints first intensify and then diminish,” she says.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Roberts explains, the only unexpurgated versions were privately printed in limited editions that were still sometimes subjected to legal action. Other translations made use of omission, euphemism, and the curious but well-established practice of giving the problematic passages in Latin, even when the original was in Greek.

So, for example, when the characters in Petronius' Satyricon find themselves embarking on an inadvertent orgy and a maid tries to arouse the impotent narrator, the Latin "sollicitavit inguina mea mille iam mortibus frigida" ["stimulated my groin, chilled by a thousand deaths"] is kept in the Latin in one version, while in another the maid -- in what sounds merely like an application of first aid --is described as "chafing my body which was icy-cold as if I had died a thousand deaths."

In the course of the twentieth century, the use of euphemism and other forms of expurgation gradually decreased. Consider the passage from Aristophanes' Lysistrata in which the heroine tells the other Greek women how they can end the ongoing war. Unless they had access to a limited-edition version, readers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries might find Lysistrata commanding the other women to abstain from "the marriage-bed" or "the joys of love." But, by the 1950s, translators could allow Lysistrata to make her point less coyly: the women of Greece must give up "sleeping with our men" or "sex.”

It was the challenge of teaching texts in translation to students without knowledge of Latin or Greek that first led Roberts to“teach about translation rather than simply through translation,” she says.“I wanted to teach ancient lyric, a genre notoriously hard to get at in translation, so I decided to handle the difficulty by focusing on translation itself, reading selections from Sappho, Catullus, and Horace along with a variety of English versions and with essays in translation theory. Since then, both my writing and my teaching have been increasingly concerned with the theory and practice of translation. And I have a lot of company: the field of translation studies is a flourishing one, bringing together people from many different disciplines.”