Roads Taken and Not Taken with Marc Zegans ’83

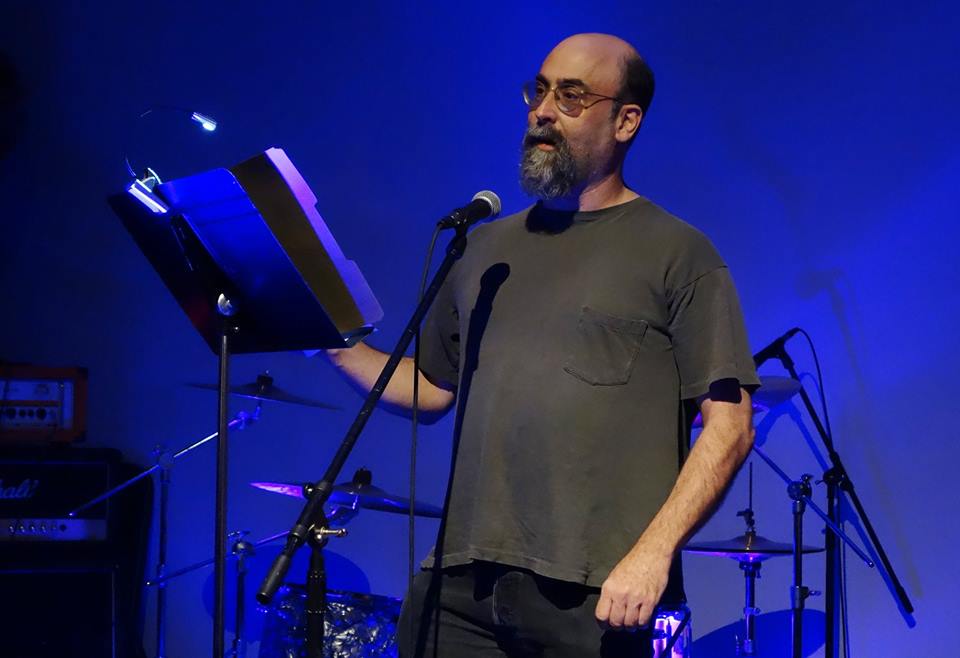

Zegans, who has published two poetry collections and two spoken-word albums, reads one of his pieces.

Photo: Mark Hanford

Details

The poet and Haverford alumnus writes about his transition from a "poemophobe" to a published author and spoken word performer

As a kid, I struggled with English grammar and I couldn’t stand poetry. Poetry, as it was presented to me and my friends, who avidly read Mad Magazine under the lifted tops of our school desks while the teacher’s back was turned, seemed alien, elitist, and meant to make us feel dumb.

One afternoon, at about age 14, I was lying on the floor of our living room in Hamden, Conn., listening to the radio on our big five-speaker, monophonic hi-fi system when something unlike anything I’d ever heard came on the air—bass, snare, and hat, and a sinuous sax, playing live over Tom Waits’ raspy smoker’s voice, delivering an “Emotional Weather Report.”

I had to hear more, so I jumped on the bus to New Haven, walked into Cutler’s record store with my $3.59-plus- tax in my pocket, and discovered that the song was part of a double album that cost $11. This was going to take saving—a lot of saving—tons of chores and a great many mowed lawns. On the day I finally broke the shrink wrap over Nighthawks at the Diner and dropped the needle on “Eggs and Sausage,” my life changed.

We didn’t have terms like “spoken word” back then. Poetry out loud, as I understood it, was flat, nasal, New England-accented recordings of Robert Frost reading “The Road Not Taken.” I didn’t know what this swing-beat, syncopated jive was, but when Waits said, “All the gypsy hacks and the insomniacs / Now the paper’s been read, now the waitress said,” I knew that—as Quakers on occasion say—“This friend speaks my mind.”

My family moved often, and our final move before I went to college was to San Francisco. While attending high school there, I began working at a recording studio called Different Fur. I particularly remember a mixing session for a KQED radio program about San Francisco poets, and specifically a poem by William Dickey called “Rainbow Grocery.” It has stayed with me over the years almost certainly because I heard it out loud.

Some months later, apprenticing to the studio’s owner, I worked on the soundtrack for Apocalypse Now, the weary drone of Martin Sheen’s voiceovers boring deeply into my mind during recording sessions that on occasion ran 17 hours.

During this period I came to understand that I process words as sound—I don’t primarily see them, even on the page. That’s probably why I had so much trouble parsing sentences in elementary school. Until I came to Haverford, though, I lacked the capacity to recognize that this difference in the way I encounter language might indeed be a gift.

During my sophomore year at Haverford, in 1981, I was taking Jack Lester’s course on the novel, and one of the books assigned was Jean Toomer’s novella Cane. I’d read it fast and had little time to finish my weekly assignment. (Jack left a basket on his front porch to which you could deliver papers by midnight Wednesday, and by some miracle, when you arrived in class Thursday afternoon, he’d read and thoughtfully responded to each one.) So I said to myself, “I’ll just write it as I hear it.”

The next day, Jack approached me after class and said, “This is good. I’d like your permission to try to have it published.” I agreed, and after slight revisions, he sent it off. The paper never saw print, but for the first time in my life, I saw that my ears in relation to words had value.

It wasn’t until I was a graduate student in public policy that I began writing poetry—quite inadvertently. One night I couldn’t sleep and found myself penning what turned out the next morning to be a poem. The muse had roused me, and for reasons that I cannot explain had led me to put down on paper words that arrived unbidden through this open channel.

Poems appeared sporadically after that, but over the years the channel began to open wider. As it did, I started writing poems more consciously and with greater attention to structure, internal music, and form. Before long, I had two lives, a secret life as a poet, writing poetry on the down low, and a public life as executive director of the Innovations Program at Harvard’s Kennedy School. This pattern continued until I had in hand a booklength manuscript, titled Catch.

At that time, I was involved in an artists’ group that I’d started with my friend Paul Bonneau, a painter. One of its members, an old friend and creative polymath, Colby Devitt, wanted to build a theater piece based on poems from Catch. So we organized a script that resulted later that year (1995) in a production called Mum and Shah.

Suddenly, I could not keep the two lives separate—people at the Kennedy School heard me talk about the production in a TV interview—and just as suddenly, a series of family and health crises made it impossible for me to give any time whatsoever to my poetry. The writing simply stopped.

In my 40s, having welcomed a child, Max, into my life, and having been through cancer and a divorce, I found myself sitting in a cabin in Point Reyes, Calif., on a writer’s retreat at Mesa Refuge. I was there to write about public management as it related to environmental stewardship, but found myself once again with the muse in my ear, and in this quiet space the words for poems once more came to me as sounds.

I was terrified to share this work—it was intimate, vulnerable, and without artifice. I was able to do so only because I wrote each piece on email and hit “Send” before I could retract the decision. In time, as I became an experienced spoken-word artist, I learned to call back this terror, but I found in this moment, on this hillside overlooking the San Andreas Fault, that developing poems with care and craft was essential to my being.

I began writing poetry systematically, and cultivated a group of fine readers with whom I could share the work. Shortly thereafter I began traveling to New York to do poetry readings. The more I appeared live, the more I became engaged with the performance aspect of poetry.

During this time I began to develop the notion of making poems as ephemeral sculpture, waves that filled space, falling gradually into hush. Two spoken-word albums, one with the late jazz pianist Don Parker, and a book followed. I also shifted the focus of my work outside poetry. I felt called to help artists thrive and shine, and I recognized that the skills I’d developed as an executive and as a management scholar were rare in the arts world, so I cultivated a practice as a creative development advisor, working both with creatively driven organizations and with artists of all stripes. I’ve been doing this for more than 15 years now and have found great joy in working with writers, visual artists, filmmakers, musicians, and other creative folks as they make crucial transitions in their creative lives.

After many years living back East, I returned to California in 2012. These days I work with clients around the world from my cottage in Santa Cruz, walk on the beach daily, and continue to write poetry. My second collection, The Underwater Typewriter, whose title poem is set in Big Sur, was published in September. Since the book’s release, I’m back to doing public readings, and have been sharing its poems from time to time on the radio. I could hardly have imagined, that afternoon when I first heard Tom Waits on my local radio station, that one day my own words would be floating on air.

Marc Zegans ’83 is a poet and creative development advisor. He is the author of the poetry collection Pillow Talk and two spoken-word albums, Marker and Parker and Night Work. His latest collection, The Underwater Typewriter, was published by Pelekinesis Press in 2015. Learn more about his work with artists at mycreativedevelopment.com.