Luis Perez ’94: The Inclusive Learning Evangelist

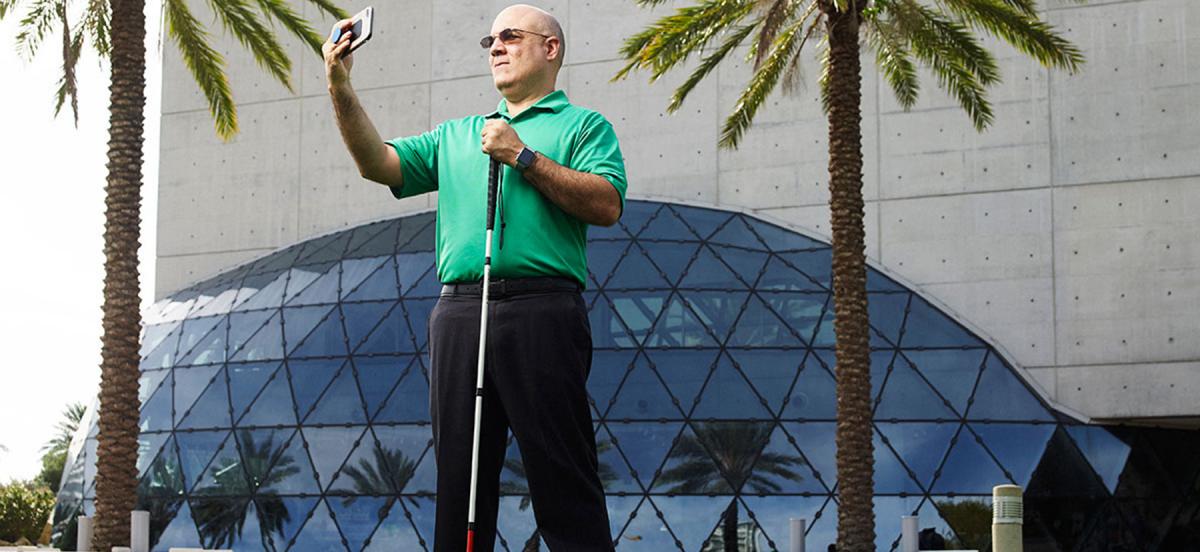

Lui Perez '94. Photo by Bob Croslin.

Details

Perez, who discovered he was legally blind at 30, is passionate about helping the education-technology community understand the crucial role it can play in giving all learners access to education and job opportunities.

Growing up in New York City, and later attending boarding school at Westtown School in Chester County outside Philadelphia, Luis Perez ’94 never needed to drive because public transportation was easier. Like most young people, he’d tried to get a driver’s license in high school, and then again in college, but “that was a really frustrating experience,” Perez says. “I repeatedly failed the driving portion of the test, which should have been a hint that something was just not right.” After the birth of his daughter, Perez moved his family to southern New Jersey, where driving was necessary, so he finally got his license. Several car crashes later, doctors diagnosed Perez with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disease that would eventually leave him legally blind. He had just turned 30. Luis Perez ’94, who is legally blind, has a passion for photography— and for getting the right supports into classrooms so that all students have the chance to succeed.

“It throws your life up into the air because so much of our lives revolve around being able to see,” says Perez. The news came as a shock to Perez, who had no idea he had the condition. He hadn’t noticed any problems with his vision while at Haverford, although looking back he recognizes the signs. It wasn’t until he started driving that the deterioration in his peripheral vision became apparent.

At first he had a hard time accepting his disability. He would forget or lose his red-tipped white cane with mysterious frequency, embarrassed that a tool he now needed branded him as different from everyone else. Fifteen years later, he has accepted that he is a disabled person, a term he prefers because his disability affects every interaction he has with the world.

But the diagnosis and increasing difficulty with his vision also sharpened Perez’s focus. He went back to school for a degree in educational technology and became interested in how technology could help students with disabilities, students like him. Perez still has some central vision, so he scans a lot when reading, but that quickly tires his eyes. The rest of the time, he relies on text-to-speech technology. He listened to many of the hundreds of pages of reading his professors assigned in graduate school; it took twice as long and was a huge adjustment for someone who preferred visual learning.

Perez would go on to get a doctorate in special education with an emphasis on Universal Design for Learning (UDL), an educational framework emphasizing that when spaces, experiences, and tools are designed for people with disabilities, it ultimately makes them more suitable for all students.

He now calls himself an “inclusive learning evangelist,” and is passionate about helping the ed tech community understand the crucial role it can play in giving all learners access to education and job opportunities. He was just hired by the National Center on Accessible Educational Materials to help schools across the country use materials all students can access, and he has even lent his expertise to Haverford as the college embarks on a UDL initiative.

“There is still a misconception out there that these technologies are cheating,” he says. It’s actually the opposite. It’s leveling the playing field.” He doesn’t want any students to miss out on an education because they didn’t have the right technological supports, tools that are much more readily available than ever before. “What’s essential for some is almost always good for all,” has become a motto for Perez as he pressures companies big and small to make their products accessible from the start.

When he’s shooting photos with his phone, white cane nearby, “I often have very deep conversations,” Perez says. People want to know how a blind man can also be a photographer.

He’s acutely aware that without his cane, people wouldn’t know that he is legally blind. The same is true for many other people with hidden disabilities, or even for children with cognitive differences, such as dyslexia. Many kids don’t know their brains are processing words differently until they start to fail. The UDL movement holds that educators should make supportive tools accessible for all students. “We shouldn’t wait until they fail,” Perez says. “We should set them up for success from the beginning.”

Advocating for the disabled community is Perez’s work, but it’s also his life; he doesn’t regard them as separate. When he received his diagnosis he felt totally alone, with no resources for making his way in the world without sight. It was a scary time. “I know I have a limited amount of time that I’ll be able to see the world,” says Perez. He’s using that time to travel, build mental models of the world and capture it all through photography, his other passion. “I wouldn’t be able to do photography if it wasn’t for digital,” he says. He can only see some of the scene he’s shooting, even though he often inverts the colors for higher contrast and uses the zoom features on his iPhone.

Even with these features, Perez admits he often doesn’t know what he has captured until he gets home and puts the image up on a big screen. He compensates in the field by taking lots of photos and mostly photographing landscapes. “I’m not a great photographer, but that’s not the point. The photos are secondary,” Perez says.

The most important part of photography for Perez is engaging with the world. “For me, it’s really the act of taking the photos that’s more important. When you have a visual impairment the world is not that inviting for you,” says Perez. It’s easy to want to disengage from the world, he says, but he chooses to be as positive as possible, and photography has helped him to embrace the world. When he’s shooting with his phone, white cane nearby, “I often have very deep conversations,” he says. People want to know how a blind man can also be a photographer. It’s another chance for Perez to talk about what the world is like for a disabled person and to advocate for inclusivity.

“To me, whenever you try to avoid naming something, that sends the message that it’s something negative,” Perez says. “This is who I am. It’s all part of the package.”