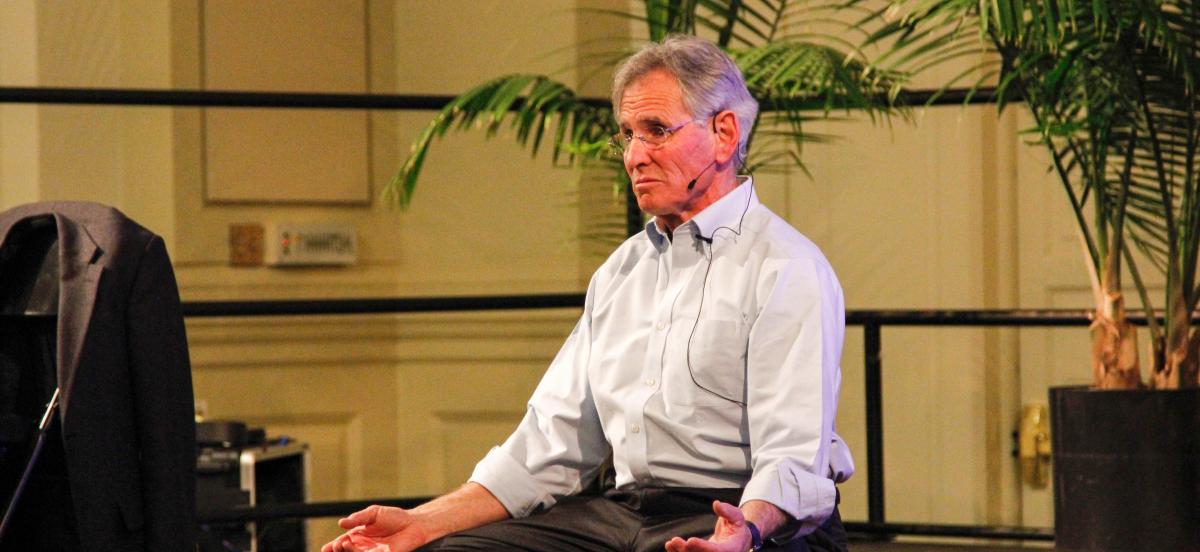

On Mindfulness and Meditation: Jon Kabat-Zinn '64

Photo by Rae Yuan '19.

Details

The Whitehead Mindfulness Initiative, which promotes good health and stress reduction in the campus community, brought the meditation pioneer back to Haverford for a two-day visit.

Jon Kabat-Zinn '64, the scientist/thinker who in 1979 melded mindfulness with medicine and launched a still-growing modern movement, looked out at the 300 people who'd come to Founders Great Hall to hear his wise words last week and asked them to check the time. He knew the answer without looking.

"It's now. Check it again. You'll notice it's now again. It has a funny habit of doing that," he said, drawing laughs.

Then he spoke more seriously and slowly: "Mindfulness is awareness. That's developed by paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, now, which is the only moment we ever have. Are you present in the timeless moments of your life?"

Kabat-Zinn returned to campus with a purpose — but also without one. His travel was paid for by the Whitehead Mindfulness Initiative, a campus program that promotes good health among students and faculty, particularly during extra stressful times. Cynthia Whitehead, widow of former Board of Managers Chair John C. Whitehead '43, started the program after her husband's death last January, initially funding it with donations sent in lieu of funeral flowers. She wanted Kabat-Zinn to share his teachings with Haverford.

"Kids on campuses today, as well as the rest of us—but the kids in particular—are so stressed out," she told the crowd before Kabat-Zinn's talk. "It's really shocking. I think a lot of them are really hurting because of it. It's very hard to meditate. It's very hard to be disciplined, but boy, is it necessary."

In an interview after one of the two guided meditation sessions he led, Kabat-Zinn, who turns down most invitations to speak that he receives, said he'd taken no payment for this trip, returning to campus "to ignite passion for what's most vital in a community of people who care. I call that love. I came for love."

Further pressed about what he hoped his visit would accomplish, Kabat-Zinn shrugged. "I'm here because I'm here," he said. "I don't even know why. Maybe 20 years from now you'll be able to tell me what the effects of this are, but I don't pretend to think anything about it. We'll see. It's just an experiment."

Over the two days of programming, Kabat-Zinn,who has authored or co-authored 11 books, including a scientific dialogue with the Dalai Lama on the healing power of meditation, urged his listeners to let go of set plans and allow days to unfold. There's a sort of magic, he said, to being open.

"Whatever you plan to do with your life, that's probably not what is going to happen," he said. "Eventually you'll realize that everything that happens in your life has a role in shaping who you end up being. Every experience gets imbibed, registered, and later, in completely unpredictable ways, has an impact."

Being open to new experiences is what changed the course of Kabat-Zinn's life. In 1965, while a molecular biology student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and "stressed out of my mind," he saw a sign inviting students to a talk on "The Three Pillars of Zen." He was one of four students to attend the event, and the introduction to meditation—to focusing on being rather than doing—laid the foundation for "Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction," the focus of both his personal and professional life for more than three decades.

MBSR seeks to ease physical and mental pain for those with chronic illness using meditation and yoga techniques. Relieving the stress in the mind, the theory goes, will relieve the stress in the body. Kabat-Zinn first introduced the program at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in 1979. Courses are now offered worldwide, and the practice is lauded by leading medical experts.

During the afternoon guided meditation, Kabat-Zinn told those gathered not to focus on being the best at meditation or the best at clearing their minds, but to focus on being. Some people, he said, become too caught up in being "enlightened," to the point that meditation isn't relaxing.

"Maybe there's no enlightenment, there are only enlightened moments and the more we string together, the more we will have the experience of being an enlightened person," he said.

Those words hit home for computer science major Anh Nguyen, '16, a regular meditator who has found herself being self-critical in her practice.

"You can really get caught up in it and that can really mess you up and cause a lot of stress," she said. "I can be very judgmental towards myself and would chide myself even while meditating if I felt I was not doing it right. The way he equates it to love and self-love, that's wonderful."

Bryan Wang '16 said he attended Kabat-Zinn's evening lecture because he felt stressed by his looming senior thesis, approaching graduation, the need to find a job, and the attendant confusion and self doubt. The next morning, while walking around campus, Wang said he felt himself focusing on simply being.

"My mind still wandered off a bit, but I was 95 percent aware of my surroundings," the psychology major said. "It really changed how I felt, to focus on being awake."

Wang initially thought he'd stop to talk to Kabat-Zinn after the guided meditation, perhaps ask him for career advice. After the session, he realized that wouldn't be helpful.

"I realized he will never be able to provide me with the answer," Wang said. "I have to seek it myself."

-Natalie Pompilio